Chicago homicides drop dramatically as police target 'hot zones'

| Chicago

Chicago’s homicide problem saw unexpectedly dramatic improvement in February, falling to levels not seen since 1957 as city police stepped up a new strategy to rein in chronic violence.

Last year ended with more than 500 homicides in Chicago, a 16 percent increase over the previous year, and this January was the bloodiest first month in 11 years. But February homicides dropped to 14, the lowest monthly total since 1957, according to police data.

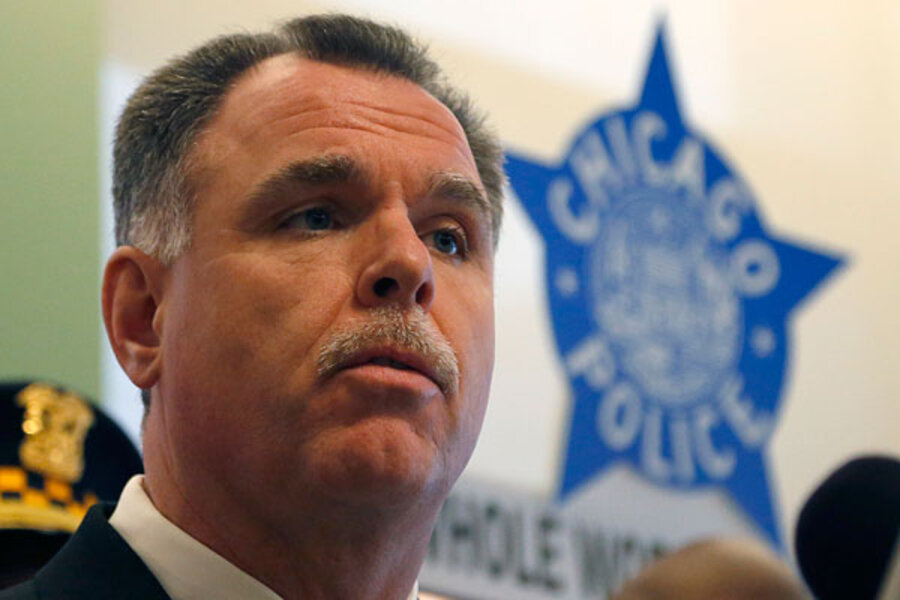

Police officials credit a new plan in which 200 officers are paid overtime and dispatched for nightly patrols to 10 “hot zones” on the South and West Sides of the city where street violence is most prevalent. Since launching the new initiative, there have been zero homicides in those areas, says Chicago Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy.

Now, he now wants officers on overtime pay sent to 10 more hot zones across the city. The idea of flooding crime-prone areas with more police officers – either on regular duty or overtime – is not new, but for police departments faced with tight budgets it is a “smart and effective” maneuver, says Tod Burke, a criminal-justice professor at Radford University in Virginia.

“It a compromise,” he says. And while criminologists are loath to link homicide rates to specific law-enforcement tactics until the data show a clear trend over a much longer time period, Professor Burke adds that the Chicago plan “may be exactly what is needed at this point in time.”

Putting more feet on the ground through overtime pay is one of many tactics police departments have been using at a time when they are hiring fewer new officers to replace those leaving for retirement, Burke says. Others include a greater reliance on community policing and technology and a more intensified effort on “hot people” who may be key figures in violence, rather than conducting large sweeps.

Superintendent McCarthy said his plan evolved from a tactic used by the New York Police Department, where McCarthy worked before going to Chicago. There, officers were dispatched from office duties to violent-prone areas on the street, a strategy that Chicago put into place last year, when its homicide rate started accelerating.

“At the end of the day, the idea is to make sure that you can’t move around in that zone without seeing a police office,” McCarthy told reporters Monday.

McCarthy would not specify which specific neighborhoods the strategy has targeted, but said that the 10 zones represent less than 2 percent of Chicago, but they are where 10 percent of the city’s violence is concentrated.

The police union worries that the city will become too reliant on overtime, which will dissuade it from making new hires.

“It’s a quick fix to a long-term situation,” says Pat Camden, spokesman for the Fraternal Order of Police in Chicago.

Mr. Camden agrees that an increased police presence in certain areas of the city will decrease crime, but argues that when Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel eliminated 1,400 department jobs to shore up $82 million for his first budget, it created a decreased police presence on the streets that the city is now trying to address.

“We wouldn’t have the situation we have right now if they didn’t eliminate specialized units like the strike force,” Camden says. “In the ideal world, I’d like to see them hiring more officers. I know it’s expensive, but so is the overtime.”

Burke says continuing to rely on overtime may help quell the violence, but it could lead to officer fatigue.

“You’re paying time and a half but you’re not paying for new officers. Saving money makes some sense, but you also have to be aware of stress and burnout levels,” he says. “At what point will it become a drain, not just on financial resources, but on officers themselves, which then puts a drain on the community?”