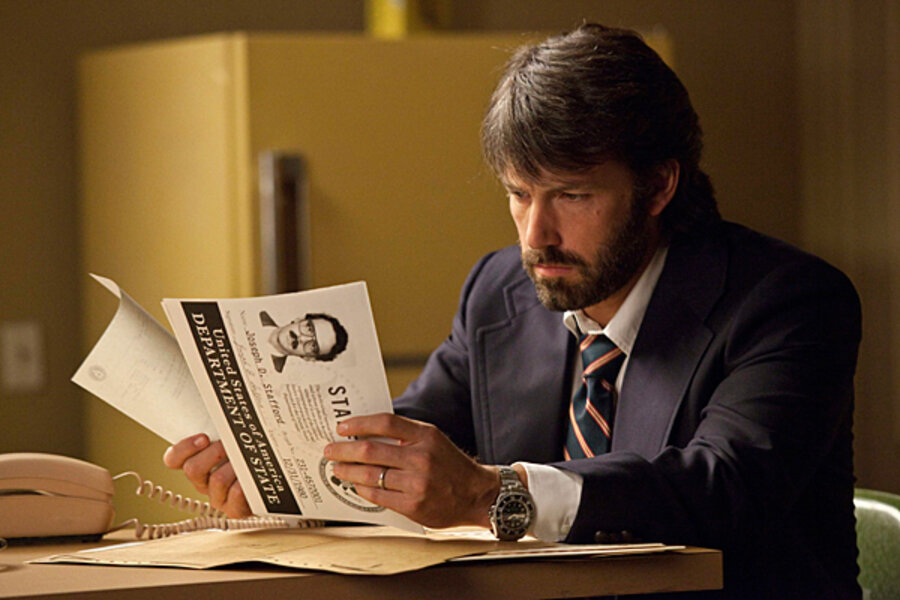

Iran plans to sue makers of 'Argo': Could lawsuit succeed?

| Los Angeles

News reports suggest that Iranian government officials are exploring the idea of suing the makers of “Argo,” saying the Oscar-winning film gave an unrealistic portrayal of Iran during the 1979 seizure of the US Embassy in Tehran. But experts say the legal prospects of such a move are exceedingly dim, suggesting that the move is likely just a publicity stunt to counteract the movie's positive publicity.

To stand any chance of success, the lawsuit would need to be brought in a country that has very loose libel laws, where the film's distributor (Warner Bros.) has assets, and where the government is antagonistic to the US, says Angel Gomez, an attorney with Epstein Becker Green in Los Angeles.

“That’s about the only way that I could see something like this working," he says. "Otherwise, it strikes me as a bit of political theater … but an interesting bit, because Iran is threatening to resort to a judicial system somewhere, instead of threatening blockades, invasions, fatwas, or other more direct actions of the past.”

Agence France Presse (AFP) reported Wednesday that Iranian officials are talking to French lawyer Isabelle Coutant-Peyre, who defended Venezuelan-born terrorist “Carlos the Jackal,” and reportedly is considering bringing the case before a court in France or perhaps in Switzerland. She calls Argo, “the historical falsification” of a movie “supposedly based on declassified” documents of the US government.

While the movie takes artistic license at some important points, it is based on the true story about how Canada and the US Central Intelligence Agency smuggled six American diplomats out of Iran after the US Embassy was taken over in 1979.

Precedent suggests French courts could consider the lawsuit, though the chances of a verdict in Iran's favor would appear remote. One thing that seems certain is that the lawsuit will not get an airing in the United States.

“Such a proposed lawsuit has absolutely no chance of getting into a US courtroom. Who is the plaintiff? What is the injury? What kind of remedy is a court supposed to impose?” says Bennett Gershman, a professor at Pace Law School in White Plains, N.Y. “I don't see how any court would even have jurisdiction to hear the complaint. This is a political, not a legal, gambit.”

But some say the case may fare better in France or Switzerland. For example, in 2011, a Israeli academic with French citizenship filed a lawsuit in French courts saying that a review of her book in the European Journal of International Law was libelous. Ultimately, the case was thrown out and the plaintiff was ordered to pay punitive damages, but “the academic community was stunned that this case was not immediately thrown out of French courts," says Jenia Iontcheva Turner, a professor at Southern Methodist University’s Dedman School of Law.

According to AFP, Ms. Coutant-Peyre says she might use Article 1382 of the French Civil Code, which is about the obligation to repair harm caused to others.

Professor Turner calls this an example of “libel tourism” or “libel forum-shopping.” "Perhaps Ms. Coutant-Peyre can get her case in the French or Swiss courts for a while and use this for publicity purposes, even if the case is ultimately unsuccessful,” she adds.

Other analysts agree that the primary motive of the potential lawsuit would not be legal. Professor Gershman of Pace Law notes that Coutant-Peyre was quoted by the Iranian Fars News Agency as saying, “These people [in Hollywood] are using films to propagate global panic about Iran. The act [of the lawsuit] itself is valuable because it can stir interest and discussion among the peoples of the world, until they can discern between what is the truth and what are lies about Iran, and think about them. The dialogue created by Hollywood [about Iran] can’t be one-sided."

The comment “means that the lawsuit is really not being brought in good faith, but simply as a political gambit. US courts don't get involved in such dishonest litigation,” Gershman says.

Other courts might have other problems, too. The question of who, exactly, has been defamed by "Argo" is unclear, says Dustin Hecker, a partner at Posternak Blankstein & Lund in Boston. “The biggest problem they have is that defamation cases are usually about individuals and there are not individuals in this film that can be identified as having been shown in a bad light," he says. "Very few courts accept the idea that you can defame an entire group.”

Turning to the United Nations International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague would also appear to be off the table, according to David Kaye, a professor at the University of California at Irvine School of Law. “Iran would need to identify some treaty basis, some legal provision in an international agreement, under which it would have authority to make a claim against the United States. I can't think of one that would exist,” he says.

Professor Kaye notes that the US appealed to the ICJ in 1979 after Iran took American hostages at the US Embassy, alleging violations of several treaties, including basic norms governing the treatment of diplomatic and consular officials.

"The ICJ decided not only that Iran violated these basic agreements but also that Iran owed the United States reparations for the hostage-taking," he says. "There is no question that the international diplomatic and legal communities saw Iran's behavior as shocking and outrageous, a major violation of the law governing protection of diplomats. That's the kind of claim that belongs at the ICJ."

In theory, a case could be filed and tried in Iran, but any legal settlement – such as monetary damages – would essentially be on hold until some representative of that entity set foot in Iran.