Why we don't know how many Americans are killed by police

Loading...

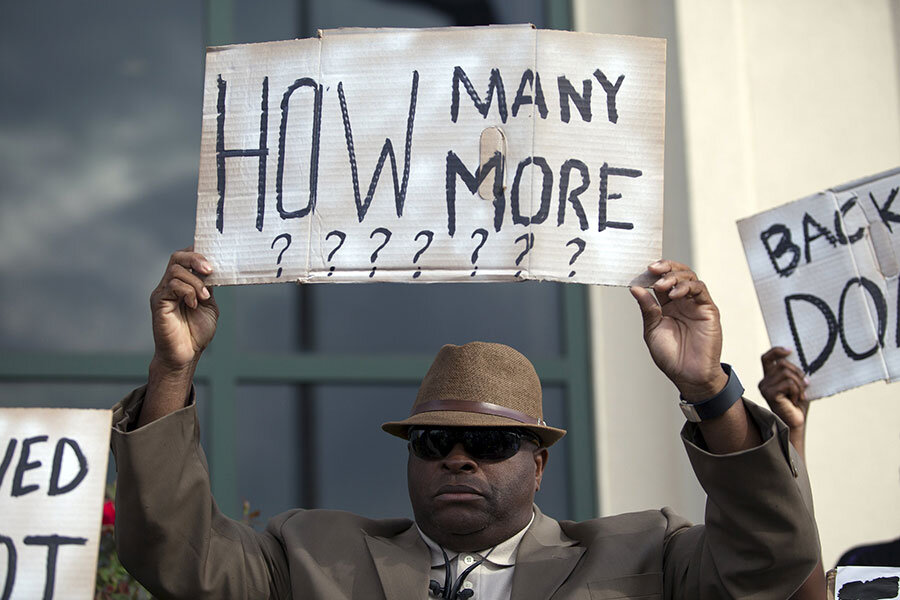

As the nation grapples with the latest incident of a police officer fatally shooting an unarmed black man – this time in South Carolina – many have asked a simple question: How often does this happen?

The answer is: No one knows for sure, exactly. Even the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Report, considered the gold standard of crime data since the 1930s, is in many ways out of date and flawed. The nation’s 18,000 law enforcement agencies are not required to compile data on officer-involved shootings.

At a time when shootings in North Charleston, S.C.; Ferguson, Mo.; and Madison, Wis., are raising awareness about the issue, such data would be crucially important to understanding where problem areas might be and how to address them, say many activists and analysts. Indeed, other police reforms, such as body cameras, independent investigations, and reforms to the grand jury system would all be of only limited value without transparent statistics, they say.

Ultimately, the only way forward, they add, is a federal law compelling police departments to compile the data and send it to the FBI. While there are no signs such a law is imminent, an array of smaller moves – together with the growing chorus of criticism – suggests there are the beginnings of movement on the issue.

In February, FBI director James Comey highlighted the problem in a speech at Georgetown University. “Not long after riots broke out in Ferguson late last summer, I asked my staff to tell me how many people shot by police were African-American in this country. I wanted to see trends. I wanted to see information. They couldn’t give it to me, and it wasn’t their fault,” he said.

“Because reporting is voluntary, our data is incomplete and therefore, in the aggregate, unreliable,” he added.

To address some of the data problems, Mr. Comey has begun an overhaul of some of the FBI’s data gathering. And last year, President Obama renewed the Death in Custody Reporting Act, which requires states that get federal money for crime programs to report anyone who died in police custody.

But these have been called poor substitutes for a stronger federal law. “First and foremost, the dearth of data surrounding lethal use of force must be eliminated,” said Walter Katz, a member of the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement, in The New York Times. “Lawmakers have to force police departments to adopt a culture of transparency where a range of data including the use of force, traffic stops and complaints are made public.”

US Attorney General Eric Holder acknowledged the need in January. “I’ve heard from a number of people who have called on policymakers to ensure better record-keeping on injuries and deaths that occur at the hands of police,” he said at a ceremony honoring Martin Luther King Jr. “I’ve also spoken with law enforcement leaders … who have urged elected officials to consider strategies for collecting better data on officer fatalities. Today, my response to these legitimate concerns is simple: We need to do both.”

Such an overhaul would likely prove politically and logistically difficult, especially since use-of-force data is not necessarily in a police department’s interest, says Thomas Larned, a former high-ranking FBI official who now works with law enforcement agencies to build better relationships with the public.

“There’s the police departments and the police officers’ unions asserting their individual rights to privacy, despite the public interest in transparency, says Mr. Larned, now a partner with the law firm Roetzel & Andress. “And there’s resistance to reporting use-of-force incidents – which of course could trigger an FBI civil rights investigation, for example.” [Editor's note: This paragraph was updated to include the Mr. Larned's current affiliation.]

Stephen Morris, assistant director of the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services division, told USA Today that it could take “years” to expand the agency’s data gathering systems. Currently, only about 10,000 of the nation’s 18,000 law enforcement agencies provide the basic summary data for the crime report, with about 6,300 participating in a more detailed data program.

Some of the country’s largest and most influential police departments, such as New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia, do not participate in the programs, USA Today reported.

“At some point, making improvements or enhancements to data systems is going to cost something to someone somewhere, and that alone can cause some agencies to say, ‘No way, not unless you’re paying for it, Uncle Sam,’ ” says Frank Scafidi, a 20-veteran of the FBI and now the director of public affairs for the National Insurance Crime Bureau.

For some local law enforcement agencies, such cooperation with the federal government could be considered a violation of their own jurisdiction.

“Look around the country, look at Congress, there are people in our country who have very strong disagreements about what the role of the federal government ought to be,” Larned says. “And those who believe that states are sovereign entities and municipalities are sovereign entities, they believe that they can solve their problems on their own. And they’re concerned, perhaps, that transparency will embarrass them.”

These are significant challenges, but not insurmountable ones, said Errol Louis, a CNN political commentator: “These hurdles could be overcome by a determined effort from Washington, but Congress has failed to press the Justice Department to demand the data ….”