Black church fires stir concern, though details still being probed

| Atlanta

Images of Southern black churches on fire have become a too-frequent sight during the past two weeks.

So far, seven have burned in the two weeks since a white supremacist murdered nine African-American worshippers at a historic black church in Charleston on June 17.

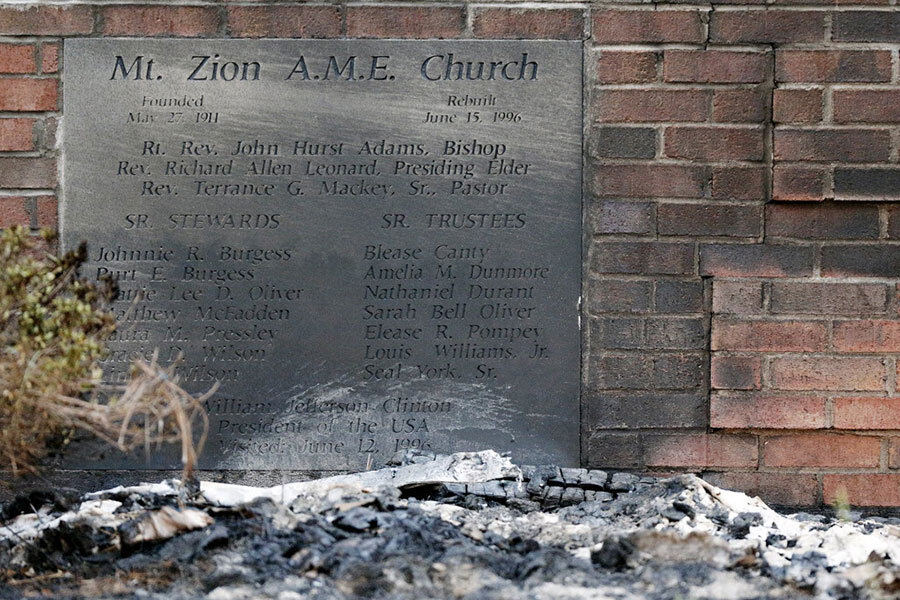

The causes of the fires remain uncertain, although three are being investigated as arson. The most recent, Tuesday’s devastating fire at Mount Zion AME, a historic African-American church in Greeleyville, S.C., likely started when a lightning bolt struck the edifice, investigators say.

But despite what investigators say so far is a lack of evidence of a pattern or racial hatred in the recent church fires, the timing of the blazes – especially when added to the historic role of the black church as a fount of power and moral authority – has fueled widespread concerns. Complicating the issue is that arson can be a particularly hard crime to solve, and motivations are often not obvious.

The concerns have deep roots: Black churches have been targets for more than 200 years. The Greeleyville church was burned down by the Ku Klux Klan in 1995, at a peak of church burnings that led to the creation of a task force that arrested hundreds of people. And the fires come at a time when the African-American church, writ large, is feeling deeply vulnerable, after one of the deadliest church attacks in modern history when Dylann Roof opened fire at the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopalian Church.

“Whatever the particulars are in the Greeleyville [and other fires], there’s precedent for concern,” says Dennis Dickerson, a Vanderbilt University historian who has written about the black church. “We hope that it turns out to be accidental or a natural occurrence, but it’s reasonable for this suspicion to be raised since [the black church] has historically been targeted by those who want to assert white supremacy.”

The images of burning churches remain searingly symbolic for a society in the process of confronting symbols of the South’s past. But before this June, church arson directed at black churches appeared to be on the wane.

While federal prosecutors convicted 25 white power arsonists in the 1990s, the last known deliberate burning of an African-American church came shortly after Obama’s election in 2008, when an arsonist set fire to the Macedonia Church of God in Christ in Springfield, Mass.

“Particularly during the 20th century, burning black churches was a way to try to intimidate blacks seeking increased political or economic power since the churches so often functioned as the hub of civil rights organizing,” Valerie Cooper, associated professor of black church studies at Duke University, tells Christianity Today.

Indeed, hundreds, even thousands, of black churches have burned since 1822, with waves of arson coming especially at times of cultural and social upheaval, whether during Reconstruction in the South, the civil rights era, or the militia movement days of the 1990s, when nearly 900 churches, many of them black, burned in the span of five years.

The black church in the 19th and 20th centuries “became a very visible target,” says Professor Dickerson. He adds, “It’s true that the church hasn’t been [targeted] in recent years, but [the targeting] is historically rooted.”

Investigators at the time found some common threads among the arsonists. “The people burning down black churches in the South are generally white, male and young, usually economically marginalized or poorly educated, frequently drunk or high on drugs, rarely affiliated with hate groups, but often deeply driven by racism,” The Washington Post’s William Booth wrote in 1996.

The church burnings in the 1990s culminated in the 1996 Church Arson Prevention Act, which was signed into law by then President Clinton after 66 black churches were burned by arsonists over a spate of 18 months. But in recent years, it has receded as a law-enforcement concern – in fact the Church Arson Task Force established in the 1990s to track such incidents disbanded.

The rate of churches that burn each year has gone from a total – including accidental and intentional – of 3,500 in 1980 to 1,700 in 2011, according to NFPA. The organization says that there's a rough average of about 180 intentional church fires that spread and do significant damage each year. The NFPA, however, doesn't keep track of whether the churches are African-American, nor do they report whether hate crime allegations result from the fires.

As to the recent spate of fires, investigators say lightning struck a black church in Florida, vandals hit a Knoxville church, and an abandoned church building burned in Macon. The Macon site also had recently been the target of robbers.

Two of the church fires – one in Knoxville and one in Charlotte, N.C. – are being investigated as arson, but fire officials say they have found no evidence that the attacks were driven by racial hatred.

To be sure, deliberate church burnings can be motivated by resentment or personal grudges or to cover up theft or another crime. And motives often remain unknown. Indeed, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Ala., attacks on churches more recently have focused mainly on mosques and Jewish temples, not black churches. In 2009, for example, the FBI reported that 72 percent of all religiously motivated hate crimes were aimed at Jews.

Perpetrators of church arson, when finally apprehended, often don’t fit the expected profiles, as shown by more than 1,000 church arson investigations conducted nationally since 1996, when the National Church Arson Task Force was established.

For example, a rash of church burnings in Alabama in 2006 were widely thought to be tied to white supremacists. But in the end, police arrested three white college students from Birmingham who admitted to burning the houses of worship after a hunting trip “joke” spun out of control.

“To know that something is motivated by hate, you either have to know who did it or they have to leave you a message in some way that makes it very obvious,” Marty Ahrens of the NFPA told the Atlantic. “There are an awful lot of [intentionally set fires] that are not hate crimes—they’re run-of-the-mill kids doing stupid things.”