Native Hawaiians: Is change in federal status a sign of progress?

A change in federal policy Friday, as the Department of Interior announced that it had finalized a rule that would allow a native Hawaiian government to form a formal government-to-government relationship with the United States.

The rule “provides the Native Hawaiian community with the opportunity to exercise self-determination,” US Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell said in a statement. It is the result of several years of meetings in Hawaii and across the rest of the US, and takes into consideration over 150 federal statutes that have been established between the United States and the native Hawaiian community in the century since the Kingdom of Hawaii was overthrown.

For some, the change in federal status is a crucial step in the right direction. Advocates say it opens the way for native Hawaiians to choose what kind of relationship they would like to have with the federal government. But opponents are concerned that the rule will — intentionally or not — obstruct the path to their goal of Hawaiian independence. What is the new federal rule a path toward?

“Native Hawaiians have been the only major indigenous group in the 50 states without a process for establishing a government-to-government relationship with the federal government,” Office of Hawaiian Affairs Chair Robert K. Lindsey said in a statement. “This rule finally remedies this injustice.”

Injustice is a common thread for both supporters and detractors of the new rule. The Kingdom of Hawaii was illegally overthrown by sugar barons and businessmen in 1893, before being annexed by the United States in 1898. In 1959, Hawaii became the 50th US state.

But it was not until relatively recently that the US began to recognize the injustice done to Hawaiians in the overthrow of their kingdom. In 1993, President Clinton issued the Apology Resolution, which acknowledged and apologized for US involvement in the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani 100 years previously. It also committed the US government to a process of reconciliation with native Hawaiians.

The Obama administration (Barack Obama was born in Hawaii) helped position the history of native Hawaiians as part of the struggle of native peoples across US territory. “The president took office vowing to strengthen the relationship between the United States government and tribal governments around the country, including the Native Hawaiian population,” said White House press secretary Josh Earnest.

This positioning is echoed by public institutions. The National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. has a special exhibit, “E Mau Ke Ea: The Sovereign Hawaiian Nation,” that opened in January 2016. The exhibit openly addresses Hawaii’s colonial past and annexation.

Former Sen. Daniel Akaka, (D) of Hawaii, worked for more than a decade on a bill that would give native Hawaiians the same rights many native Americans and Alaska natives enjoy. The bill was repeatedly blocked from being voted on.

In order to pursue the government-to-government relationship established by the new rule, a recognized government needs to represent the native Hawaiian community. At present, no such government exists. According to the Interior Department, a new government would need a governing document ratified by native Hawaiians. Last year, a constitutional convention was held, but crumbled after a lawsuit questioned the legality of a race-based election. Similar questions may affect efforts to create a native Hawaiian government.

Some say that this governing document already exists, however. They point to the constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii, a prominent symbol for those advocating for Hawaiian sovereignty. For some native Hawaiians, a government-to-government relationship with the United States is unnecessary – and undesirable. They say formalizing this relationship would impede progress toward full sovereignty.

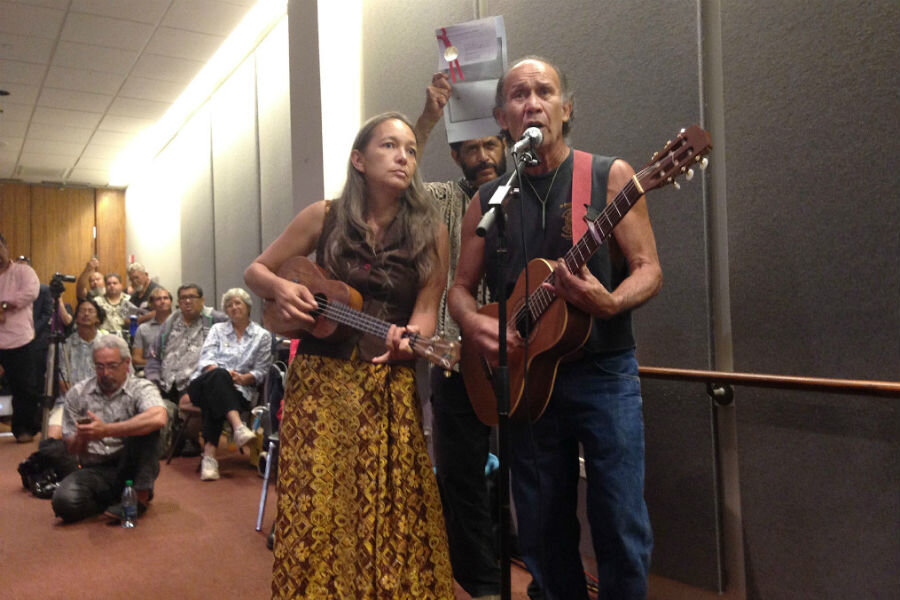

“No to everything that you guys are wanting and everything you are wanting to do,” Kale Gumapac told a public meeting convened by the federal government to discuss the rule in July 2014. “Because we can do it ourselves. We have our own government. We have the Queen, Liliuokalani, and the constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii continues to exist."

But for others, like Sen. Brian Schatz (D) of Hawaii, the new rule is “a historic step in the right direction.” Annul Amaral, the president of the Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs, expressed optimism that it would give native Hawaiians more agency over issues in their daily lives. “What it allows us to do is to finally have control over our sacred sites, over health care for our people, over the education of our children… [W]ith our own government we can begin to initiate change,” she told Hawaii Public Radio.

The change in federal status indicates that some kind of progress is possible — even if it does not look like the progress that some native Hawaiian activists had sought. But it is certainly not the end of the conversation. It may open the way for a larger discussion of Hawaii's future.

"Once Native Hawaiians establish [their] own government, only at that time will there be a determination of do we want to seek federal recognition, do Native Hawaiians want to go with independence, do they want to maintain status quo," Keali’i Lopez, the board president of Imua Hawai‘i, told Hawaii Public Radio. "So what the Department of the Interior and President Obama have done is just create the pathway. It's going to be up to Native Hawaiians to choose what path they take."