Police lineups are flawed: New study

Loading...

| WASHINGTON

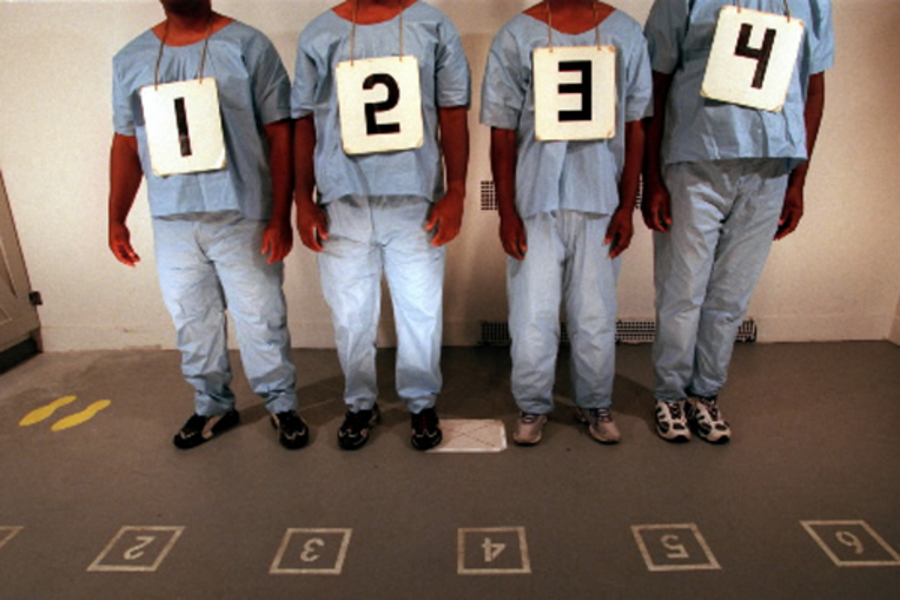

A new study says those lineups you see on television crime dramas and often used in real-lifepolice departments are going about it all wrong.

The study released Monday by the American Judicature Society is part of a growing body of research during the past 35 years that questions the reliability of eyewitness identifications under certain circumstances. That research has been taken more seriously in recent years with the evolution of DNA evidence clearing innocents of crimes they were convicted of committing, often based on eyewitness testimony.

The new study finds witnesses should not look at a group of people at once to pick a perpetrator. Instead, they should look at individuals one-by-one with a detective who doesn't know which is the real suspect — known as a double-blind lineup to avoid giving witnesses unintentional cues — preferably on a computer to ensure appropriate random procedures are used and to record the data.

The study found witnesses using the sequential method were less likely to pick the innocents brought in to fill out thelineup. The theory is that witnesses using the sequential lineup will compare each person to the perpetrator in their memory, instead of comparing them to one another side-by-side to see which most resembles the criminal.

"What we want the witness to do is don't decide who looks most like the perpetrator, but decide whether the perpetrator is there or not," said Gary Wells, an eyewitness identification expert at Iowa State University and the project's lead researcher.

Wells said the results confirmed many other laboratory experiments that have found sequential lineups to be more accurate. But he said some police departments have been reluctant to change their practices, wondering if they would apply to real-life witnesses.

This study used actual witnesses who didn't know they were part of a study, but were randomly assigned to use either the sequential or the simultaneous method. It was conducted at the police departments in Austin, Texas; Charlotte-Mecklenburg, N.C.; San Diego and Tucson, Ariz.

The witnesses were shown mug shots of one suspect with five "fillers," or the known innocents. In the simultaneouslineups, the witnesses picked a filler 18 percent of the time, verses 12 percent for the sequential method. Witnesses picked the suspect about a quarter of the time using both methods.

Wells estimates that between 20 and 25 percent of 16,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States are using the sequential and double-blind procedures. He said those reforms have been made in the last decade, with some key departments including Denver and Dallas coming on board just this year. "There's still a long ways to go," he said. He said he hoped this study would help push reforms forward.