USS Zumwalt warship's namesake fought racism, sexism

Loading...

| BATH, Maine

Bud Zumwalt took what he learned during the tumultuous 1960s with him when he became the nation's youngest chief of naval operations, earning a reputation as a reformer who fought racism and sexism and worked to improve the lives of sailors.

After retiring, the admiral dedicated his life to ensuring that veterans were compensated for illnesses linked to Agent Orange, an herbicide he had approved in Vietnam and he blamed for the death of his son.

Zumwalt's two daughters will christen a new ship that bears his name on Saturday at Bath Iron Works. Joining them will be his surviving son, who is a retired Marine, and other relatives.

The young leader turned the establishment on its ear, helping to create a modern Navy that embraced equal rights, said Larry Berman, who wrote a book about him.

"Zumwalt came in and smashed that entire system," Berman said. "He thought it was a racist system. He felt it was appalling that the Navy had only three black captains."

Like its namesake, the new ship is modern, innovative and potentially game-changing, with a stealthy shape, composite superstructure, wave-piercing tumblehome hull, electric propulsion and new radar and weaponry. Thanks to unprecedented automation, it will set sail with a crew that's nearly half the size of the complement on existing destroyers.

At 610 feet long and 15,000 tons, it is the largest destroyer built for the Navy.

In World War II, Elmo "Bud" Zumwalt Jr. earned the Bronze Star while serving on a much smaller destroyer during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. After the war, George Marshall, the Army general and statesman, persuaded him to stay in the Navy.

In Vietnam, his commanded included small boats that patrolled the Mekong Delta. It was during that time that he approved Agent Orange to remove vegetation that provided enemy cover.

His leadership during the 1960s helped to prepare him for changes he felt were necessary when, at age 49, he became chief of naval operations in 1970. His memos, dubbed Z-grams, altered the Navy's course.

He eased restrictions on hair, beards and sideburns, allowed beer machines in some barracks, mandated that black barbers and beauticians be hired to help cut the hair of black sailors, and required hair products for black sailors be sold on bases. He also created an ombudsman to give Navy wives a voice.

But the biggest changes eliminated barriers for women and minorities to advance. By the time he retired four years later, the Navy had its first black and female admirals, and women were soon serving aboard warships and flying Navy aircraft.

He "bent the institution of the Navy toward justice," said Capt. James Kirk, commanding officer of the Zumwalt.

While some in the Navy establishment fought Zumwalt, sailors loved him because he listened to their concerns and tried to make their lives better. Zumwalt liked to joke, "I have a long list of friends and a long list of enemies, and I'm equally proud of both," said Berman, author of "Zumwalt: The Life and Times of Admiral Elmo Russell 'Bud' Zumwalt, Jr."

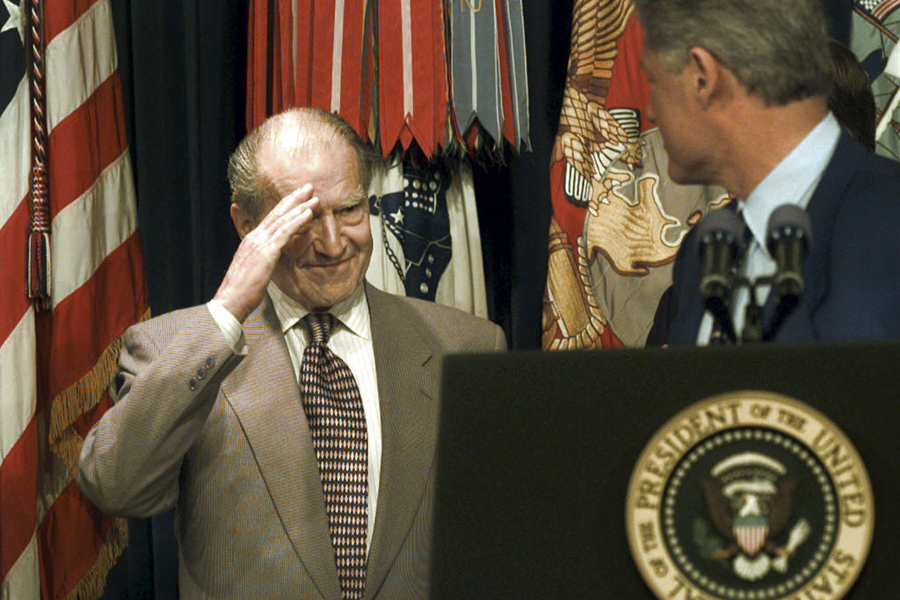

Former President Bill Clinton, a friend, described him as "the conscience of the Navy" after his death at age 79 in 2000.

After retiring, Zumwalt learned chemical companies had lied to him about the safety of Agent Orange, which he blamed for the death of his firstborn son, Elmo R. Zumwalt III, a swift boat skipper. His efforts on behalf of sickened veterans and their families helped earn him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

To see Zumwalt's legacy, one needs look no further than the new ship's crew. Department leaders include two women, one who is black and another who is of Hispanic descent.

"The single most important legacy that he left behind is that he brought the Navy into the 20th century," Berman said.

Even on his tombstone, the author said, there is the word "reformer."