70 years later, judge rules 14-year-old boy was wrongly executed

Loading...

| Columbia, South Carolina

More than 70 years after South Carolina sent a 14-year-old black boy to the electric chair in the killings of two white girls in a segregated mill town, a judge threw out the conviction, saying the state committed a great injustice.

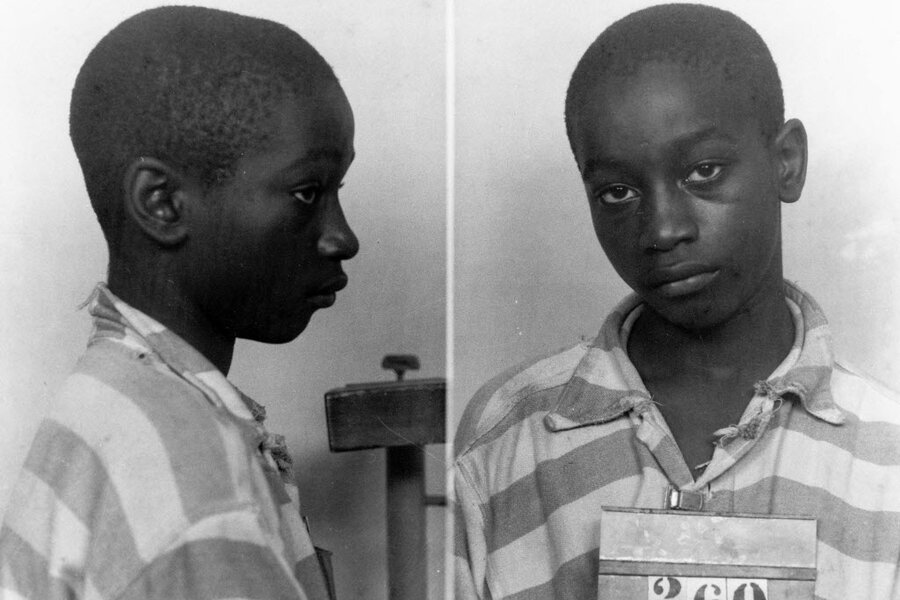

George Stinney was arrested, convicted of murder in a one-day trial and executed in 1944 — all in the span of about three months and without an appeal. The speed in which the state meted out justice against the youngest person executed in the United States in the 20th century was shocking and extremely unfair, Circuit Judge Carmen Mullen wrote in her ruling Wednesday.

The girls, ages 7 and 11, were beaten badly in the head with an iron railroad spike in the town of Alcolu, authorities said. A search by dozens of people found their bodies several hours later.

Investigators arrested Stinney, saying witnesses saw him with the girls as they picked flowers. He was kept away from his parents, and authorities later said he confessed.

His supporters said he was a small, frail boy so scared that he said whatever he thought would make the authorities happy. They said there was no physical evidence linking him to the deaths. His executioners noted the electric chair straps didn't fit him, and an electrode was too big for his leg.

During a two-day hearing in January, Mullen heard from Stinney's surviving brother and sisters, someone involved in the search and experts who questioned the autopsy findings and Stinney's confession. Most of the evidence from the original trial was gone and almost all the witnesses were dead.

It took Mullen nearly four times as long to issue her ruling as it took in 1944 to go from arrest to execution.

Stinney's case has long been whispered in civil rights circles in South Carolina as an example of how a black person could be railroaded by a justice system during the era of Jim Crow segregation laws where the investigators, prosecutors and juries were all white.

The case received renewed attention because of a crusade by textile inspector and school board member George Frierson. Armed with a binder full of newspaper articles and other evidence, he and a law firm believed the teen represented everything that was wrong with South Carolina during the era of segregation.

Frierson said he heard about the judge's decision from a co-worker. He had to attend a school board meeting later in the day, so the news hadn't sunk in yet.

"When I get home, I'm going to get on my knees and thank the Lord Almighty for being so good and making sure justice prevailed," Frierson said.