Budget stalemate: Why America won't raise taxes

Loading...

| Washington

It was a secret meeting in a city that doesn't keep secrets well, so the congressional and administrative officials agreed to gather at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland, away from the glare of the media and anyone who might leak information. Over a series of mind-numbing days, during an intense heat wave, the principals crunched numbers and jockeyed for political advantage. The goal: taming the ballooning budget deficits of the Reagan era.

In the end, Democratic leaders in Congress and aides to President George H.W. Bush both ceded ground. Democrats would accept some cuts in entitlements, while the president would break his famous "read my lips" promise – and raise taxes. President Bush announced the plan from the Rose Garden: It would cut $119 billion from entitlements and $182 billion from discretionary programs while raising tax revenues by $134 billion, mostly through an increase in gasoline taxes.

But the package hit an unexpected roadblock. House conservatives – led by Newt Gingrich, whom Bush had believed to be an ally – revolted, joining with liberal House Democrats to block the plan. For Bush, it was "the most unpleasant, or tension filled" week of his presidency.

"I hate the posturing on both sides," Bush recorded in his diary. "[People] putting their own selves ahead of the overall good."

Eventually they did pass a budget, which raised income-tax rates for the wealthy and imposed new taxes on luxury goods and tobacco. Only one-quarter of Republicans voted for it, and many remained furious with the president. Two years later, Bush would lose reelection to Bill Clinton.

It was a seminal moment in what has been a subtle but significant shift in the politics of Washington. For generations, Republicans have resisted tax increases. As far back as the 1920s, conservative Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon was arguing that "high rates of taxation do not necessarily mean large revenue to the government, and … more revenue may actually be obtained by lower rates."

But in recent years, the aversion to taxes has become more deeply ingrained. It is more than a policy preference, more than a tenet in a party platform. For many Republican officeholders, raising taxes is a subject they simply won't broach anymore – period. If there is a third rail of politics today, it might not be Social Security. It might be tax increases.

Raising levies is not a part of the long-term budget blueprint outlined recently by Rep. Paul Ryan (R) of Wisconsin, which would cut nearly $6 trillion in spending over the next decade and transform Medicare. In fact, Mr. Ryan proposes lowering corporate and upper-income tax rates.

President Obama did call for raising taxes as part of his long-range budget plan unveiled April 13. Mr. Obama, seeking to reduce the deficit by $4 trillion over 12 years, suggested his plan was a more balanced approach that relies on both spending cuts and an increase in taxes on the wealthy. Yet the tax increase will be one of the most contentious parts of his plan.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to reflect the settlement of the federal government's budget impasse on April 8.

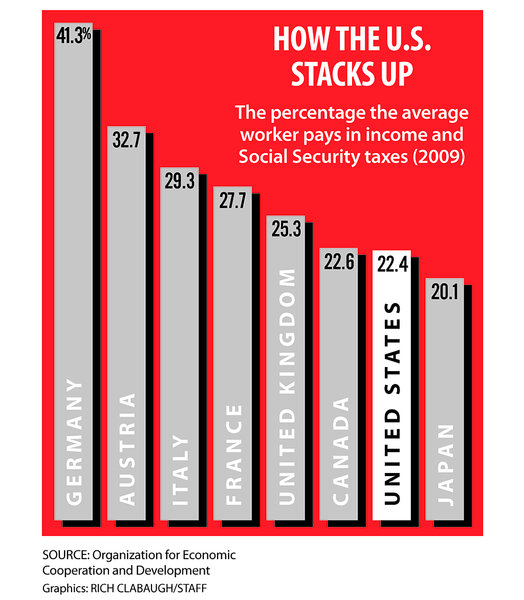

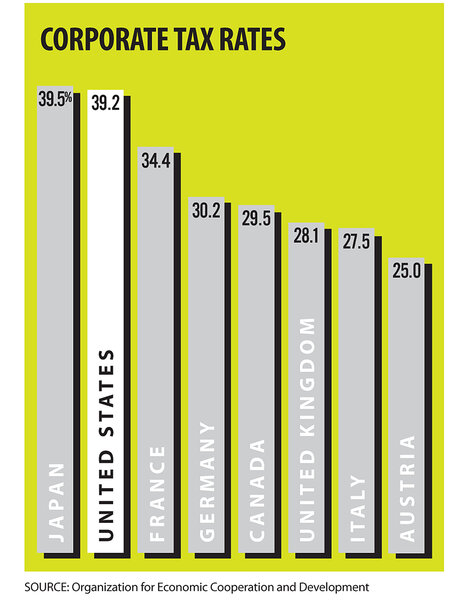

The antitax ethos has been shaped by both politics and principle. To tax opponents, the overall tax burden is still needlessly high – the US corporate tax rate, for example, is one of the highest in the industrialized world – suppressing the activity of businesses and individuals who would otherwise use those resources to stimulate the economy and create more jobs. They say higher taxes would just feed an already bloated government that is getting inexorably bigger by the day. As the nation once again grapples with staggering deficits and some $14 trillion in debt, the real problem, they insist, isn't a lack of revenue. It's too much government spending.

"The federal government is too big and too wasteful and too inefficient," says former GOP House majority leader Dick Armey, who now heads FreedomWorks, a tea party affiliated group.

To critics, however, the refusal to even consider raising taxes is threatening the nation's financial future. Democrats and many independent analysts argue that the debt problem is just too big to be tackled through spending cuts alone, and that any eventual solution must involve higher revenues.

Yet budget negotiations of the sort George H.W. Bush presided over in the early '90s – in which Democrats pushed for higher taxes and Republicans pushed for spending cuts and they met somewhere in between – don't seem to exist anymore. Instead, lawmakers get locked into intractable standoffs in which they can agree on only a smattering of minor spending cuts, while putting off resolving the deeper economic problems.

"We've sort of lost the capacity to raise taxes under any circumstances," says Joseph Thorndike, director of the Tax History Project at Tax Analysts, a nonprofit group in Falls Church, Va. "And as long as tax increases are off the table, then spending controls are off the table, too. There's no happy ending to this story."

* * *

One gauge of how institutionalized antitax sentiment in Washington has become is a single-sentence statement known as the "Taxpayer Protection Pledge." Issued by Americans for Tax Reform (ATR), a Washington-based antitax group, it asks candidates for elective office to agree to oppose "any and all" hikes in income-tax rates for individuals or businesses, as well as any elimination of deductions or credits unless offset "dollar for dollar" by further reducing rates.

When first introduced in 1986, according to ATR president Grover Norquist, 100 House members and 20 senators signed on. Since then, the number has crept up steadily, to the point where now more than half the members of Congress have agreed to the pledge: 40 out of 47 Republicans in the Senate, along with one Democrat and one Independent. In the House, 235 out of 242 Republicans have signed on, along with two Democrats – a high-water mark, according to Mr. Norquist.

"It is a factor in every Republican primary," says Norquist. "[Candidates] know voters reward people who take the pledge and punish people who raise taxes."

Even talking about raising taxes can get a lawmaker in trouble. Recently, three Republican Senate members of the bipartisan "Gang of Six" working behind the scenes to come up with a compromise on deficit reduction suggested that revenues would have to be "on the table." Immediately, Norquist sent a public letter warning that any tax package that wasn't "revenue neutral" – that didn't include the same amount in tax decreases to offset any tax increases – would violate the pledge.

The three senators responded with a placating letter of their own, saying: "Like you, we believe tax hikes will hinder, not promote, economic growth," adding, "we look forward to again working with you and all interested parties to support a proposal where any increase in revenue generation will be the result of the pro-growth effects of lower individual and corporate tax rates for all Americans."

So far, most pledge signers have remained remarkably true to their word. If you look over recent tax enactments by Congress, the trend is clear. Over the past 15 years, according to the Washington-based Tax Policy Center, the only piece of major tax legislation passed that increased taxes was the Obama health-care plan, which will impose new levies on upper-income taxpayers starting in 2013. By contrast, some 18 major pieces of legislation have been enacted since 1997 that have served to reduce the tax burden in one way or another, either through rate cuts or deductions and credits.

The most recent was the move last December to extend the George W. Bush tax cuts. The vote came just weeks after President Obama's Deficit Reduction Commission released its report calling for reduced spending, entitlement reform, and higher tax revenues.

Yet with the economy still recovering from recession, Congress voted to extend the tax cuts across the board for two more years, despite numerous polls showing voters favored letting them expire for the wealthiest taxpayers. Several Republicans eyeing a White House run – including Mr. Gingrich and former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney – criticized lawmakers for not extending the tax cuts permanently.

"I don't think there's any conceivable way, under current circumstances, that any Republican would vote for any kind of tax increase whatsoever," says Bruce Bartlett, a former economic adviser to President Reagan and a Treasury official during the first Bush administration, who has become an outspoken critic of the Republican Party's current economic policies. "Republicans are absolutely convinced that to support tax increases guarantees their [electoral] defeat."

Nor is the aversion to taxes just a Washington phenomenon. Many states are facing severe economic crunches that may worsen over the next fiscal year as the flow of federal stimulus dollars comes to an end. In response, most Republican and even many Democratic governors are aggressively slashing spending, while generally holding tax increases at bay.

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, all of the 48 states that have released budget proposals for fiscal year 2012 (which begins on July 1) are proposing deep spending cuts in areas like education, Medicaid, and public employee salaries in order to address budget gaps, while just seven of those states are opting to offset some of those cuts with tax increases. In fact, for the first time since the recession hit, governors of at least seven states – from Wisconsin to Florida to New Jersey – are now proposing large tax cuts, mostly for corporations, which they believe will boost economic growth.

"At the state level, they've been really resistant to raising taxes, even though they've got a dramatic need to do it," says Len Berman, a tax policy expert at Syracuse University in upstate New York.

Several Republican governors, including Scott Walker in Wisconsin, John Kasich in Ohio, and Rick Scott in Florida, also turned down billions of dollars in federal stimulus money that would have gone toward building high-speed rail projects (and, critics contend, would have created thousands of jobs), because they believed the projects would create a future tax drain on their states.

"I just spent a day with the governor of Florida – he's not raising taxes, period," says Norquist. The same goes for New Jersey, Ohio, Wisconsin, Indiana – "you're going to get real spending restraint in those states."

Historically, this has not always been the case. True, politicians have never been eager to raise taxes. But in the past, when economic crises hit, lawmakers have often turned to taxes as part of the solution.

Many of these crises, not surprisingly, came in the form of wars. The nation's first income taxes were levied to help pay for the Civil War. Repealed shortly thereafter, income taxes came back permanently in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment, enshrining in the Constitution the federal government's right to collect them directly. They became the biggest source of revenue for Washington during World War I.

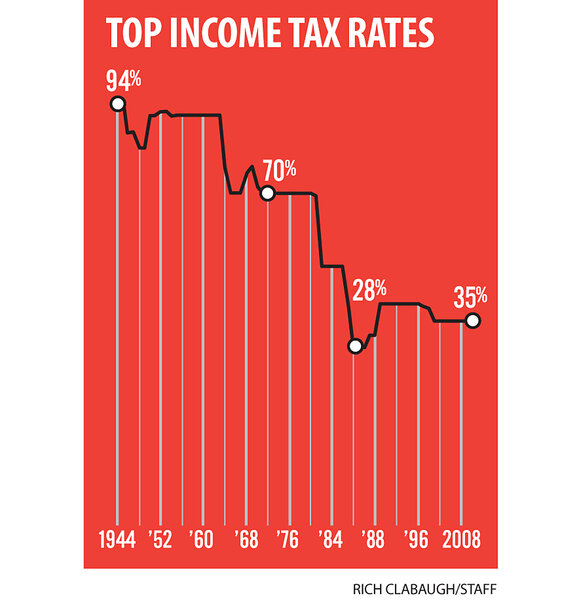

Lawmakers lowered rates after the war ended, but then increased them again during the Great Depression and raised them even higher during World War II – when the top marginal tax rate hit a staggering 94 percent.

Interestingly, in the war's aftermath, Republican President Dwight Eisenhower and the GOP-controlled Congress chose to leave rates relatively high. During the 1960s, Congress began lowering taxes again, repeatedly bringing them down over the next two decades – but because tax brackets weren't indexed to inflation, which was rising, the overall tax burden on Americans actually increased.

The single biggest change in the postwar era came during the Reagan administration, with the Economic Recovery Act of 1981 – which slashed the top marginal tax rate by more than half. It was a hinge moment for the conservative antitax movement.

"[Reagan] was clearly a passionate tax-cutter, and a little of a devil-may-care tax cutter, at least in the beginning," says Mr. Thorndike. But it didn't last. Just one year after pushing massive tax cuts through Congress, as his advisers grew nervous about spiraling deficits, Reagan agreed to a tax hike, followed by another in 1983, and another in 1984 – restoring roughly 40 percent of the taxes he'd originally cut.

By the time of Reagan's reelection, in 1984, inflation had finally been conquered and the economy was mending. Some former Reagan advisers argue that Republicans internalized the wrong lesson from the period.

"[T]he new tax-cutters not only claimed victory for their supply-side strategy but hooked Republicans for good on the delusion that the economy will outgrow the deficit if plied with enough tax cuts," wrote David Stockman, Reagan's director of the Office of Management and Budget, in The New York Times last summer.

But perhaps an even more critical factor for lawmakers in the years since has been a lack of immediate consequences of deficits on consumers. During the Reagan-Bush years, big deficits still had the power to create a sense of fiscal emergency: They were seen as a drag on the economy and, coming at a time of high inflation and high interest rates, they added to the pressure to control budgets in whatever way possible. Today, that's not the case.

"In the last 25 years or so, we've had relatively low interest rates," says Mr. Bartlett. As a result, "whatever logical linkage people had in their minds between deficits and things that affect things in their lives has been broken." Without that direct link, even lawmakers who might be somewhat sympathetic to fiscal arguments for raising taxes have had far less incentive to risk the political consequences of such a move.

And lately, the likelihood of political consequences has only increased. As tea party and other activist groups target Republican members who fail to uphold conservative economic principles, they are making lawmakers less willing to stray from fiscal orthodoxy.

"The members who try to approach this thing intellectually and honestly – they get called out," says political analyst Charlie Cook of the Cook Political Report. "More traditional, mainstream Republicans – they are being terrorized, and it is affecting behavior."

The defeat last spring of Utah Sen. Bob Bennett was a case in point – and one that reverberated through Republican circles. Many activists saw Mr. Bennett, despite an American Conservative Union ranking of 84 percent, as insufficiently committed to smaller government, as evidenced by his support for the Wall Street bailout and his unapologetic use of earmarks. The Club for Growth, a small-government, antitax group in Washington, decided to try to pick him off.

"Bennett was seen as part of the problem," says David Keating, the club's executive director. "We were the only group to spend any money – we spent about $200,000, which, when you think about it, is extremely cheap." Bennett was slow to perceive the danger, and wound up losing the primary contest to tea party favorite Mike Lee, who went on to win the general election. The Club for Growth also played a key role in defeating former Gov. Charlie Crist in the Florida Senate race and pushing former Sen. Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania out of the GOP and eventually out of Congress.

According to Mr. Keating, the total amount of money the club has spent on elections, through its various political arms, has nearly tripled in the past decade – from $8.7 million in the 2002 cycle to just over $23 million in the last cycle. And its overall influence may be far greater. Like Americans for Tax Reform – which pressures candidates to sign its "no new taxes" pledge during the campaign and then monitors their votes and public statements to make sure they comply – the club has become a kind of guardian of Republican values, whose stamp of approval (or disapproval) can be critical.

This time around, conservative activists are looking hard at GOP Sens. Richard Lugar in Indiana and Orrin Hatch in Utah. Notably, Mr. Lugar is one of the few Republican senators who has refused to sign ATR's "no new taxes" pledge. Keating notes that Senator Hatch, feeling the pressure, is now "voting to the right of most every senator." Still, he says, "you have to look at his whole record. We're not really sure if he's had a genuine change of heart."

One question is whether many grass-roots conservatives, particularly tea party conservatives, are driven more by antitax sentiments or by concerns about the deficit – and more important, if they'd be willing at some point to sacrifice one priority for the other. Leaders insist it's a false choice – that the best way to reduce the deficit is by slashing spending and stimulating the economy through lower taxes, and that you won't get one without the other. They also believe high tax revenues reduce the incentive for lawmakers to make hard spending choices.

"When countries have tried to reduce the deficit with tax increases plus budget restraint, it never works," says Norquist.

Yet tax cuts don't automatically lead to spending cuts: The growth of the tea party movement can be traced in part to frustration with the Republican Party's failure to rein in spending under President Bush – despite his many tax cuts – as well as anger at the Obama administration's policies.

"Quite frankly, the Republican Party for the last seven or eight years prior to the last election was pretty disappointing to small-government conservatives," says Mr. Armey.

* * *

In fact, there are some indications the public at large may be softening in overall attitudes toward taxes. Since the end of World War II, Gallup has asked Americans every year whether the amount they pay in federal taxes is too much, about right, or too little. Consistently, the top answer has been "too much" – until recently, when pluralities began saying their taxes were "about right."

The shift hasn't been consistent over the past three or four years, "but it's there – you see it," says Karlyn Bowman, a public opinion expert at the American Enterprise Institute. It could simply reflect that more Americans were removed from the tax rolls altogether during the recession – and thus don't have any argument with rates. Or it could reflect a genuine sense among many Americans that their taxes are not, in fact, too high.

Even among those voters who are most unhappy with federal taxes, when asked whether it's the amount they're paying that they object to or how the money is being spent, "it's how the money's being used" that troubles most, says Ms. Bowman.

David Kirk, for one, would be willing to pay more in taxes if he felt the government would use it wisely. To Mr. Kirk, the service manager for a forklift company in Burlington, Vt., that would mean putting more of it toward reducing the deficit rather than what he considers wasting it. Otherwise, he wants the government to keep its hand out of his pockets.

"I think that my family has to live within the dollar amounts that we earn, and so should the government," he says during a visit to Boston's Faneuil Hall.

Others feel the same way about state government. Dave Matherne, a salesman in Alabama for Cintas, a uniform and apparel supply company, won't be getting any taxes back from the state this year. He'll have to pay in, which angers him.

"I don't feel like we get back enough for what we pay into federal, but I'm OK with that," he says. "But the state is just ridiculous. You always hear them talking about how much they give to education, but you look around and it seems like schools don't get enough."

Many Americans, of course, want it all: They tell pollsters that they would prefer not to raise taxes or cut spending – and yet they also want Congress to address the deficit. It's one problem with polling on tax attitudes: Questions are typically asked in isolation, and thus people often give contradictory answers.

But, according to Steven Kull, director of the Center on Policy Attitudes at the University of Maryland, when voters are presented with more detailed information – and given the opportunity to make their own trade-offs – they're usually quite pragmatic.

Mr. Kull's group presented voters with a simplified but realistic version of what the budget might be in 2015 and then let them make their own tax and spending choices. They weren't told they had to balance the budget – whether to bring the deficit down or not was up to them. The result: On average, voters reduced the deficit by some $400 billion.

The average voter cut some $145 billion in spending, with Democrats actually cutting more than Republicans. And 91 percent of respondents – including 77 percent of Republicans and 66 percent of self-identified tea partyers – chose to raise taxes by an average of $292 billion.

"Congress has gotten itself in a position where they feel various pressures, primarily from organized groups, and their tendency is to assume that the totality of organized groups is representative of the public as a whole – and that's a big mistake," says Kull. "The average person is not wedded to any particular position."

Indeed, some say Americans have never been as opposed to taxes as the national mythology would suggest. "We've got remarkably high compliance rates," says Mr. Thorndike of the Tax History Project. "You might just as well marvel that Americans have been as willing as they are to pay taxes."

At the Boston Tea Party, after all, colonists weren't refusing to be taxed on principle – they were rebelling against taxation without representation. If there's one overarching tax attitude that has always resonated with the public, it's fairness.

Americans are generally willing to pay into the system as long as they feel it is working for them and that everyone else is also paying their fair share. It's when they sense others are scamming the system, or finding ways around it, that trust – and tolerance for taxation – evaporates.

In the past, politicians have effectively used this argument to push for tax reform and to raise new revenue. President Franklin Roosevelt was a master at this, defending a series of tax increases, largely on the rich, in the name of battling tax avoiders. Reagan also relied on a sense of public outrage when selling his 1986 tax reform bill.

That bill – which eliminated loopholes and deductions, broadening the tax base while also lowering rates – was similar in some ways to the tax proposals recently offered by the Deficit-Reduction Commission, and now being considered by the Gang of Six in the Senate.

Still, unless the changes come in a "revenue neutral" package, as in 1986, it's hard to see how they would pass the GOP-controlled House. And Democrats and many independent analysts say a package without more tax revenue won't do enough to solve the deficit problem this time.

America has faced serious fiscal challenges before. But what makes this situation unusual is both the scope of the problem – historic deficits and debt levels, which are only projected to worsen as the Baby Boom generation ages – and the fact that it is happening at a time when political resistance to raising taxes appears stronger than ever.

As a result, the country may be about to embark on its grandest test yet of a bedrock conservative principle – the idea that nation's wildly unbalanced bank account can be fixed largely by spending cuts alone.

If successful, it could lead to a wholesale change in the size and function of government. If not, it could lead to fiscal peril – and perhaps another revolt at the ballot box.

• Carmen K. Sisson contributed to this report from Mobile, Ala., and Ilana Kowarski from Boston.