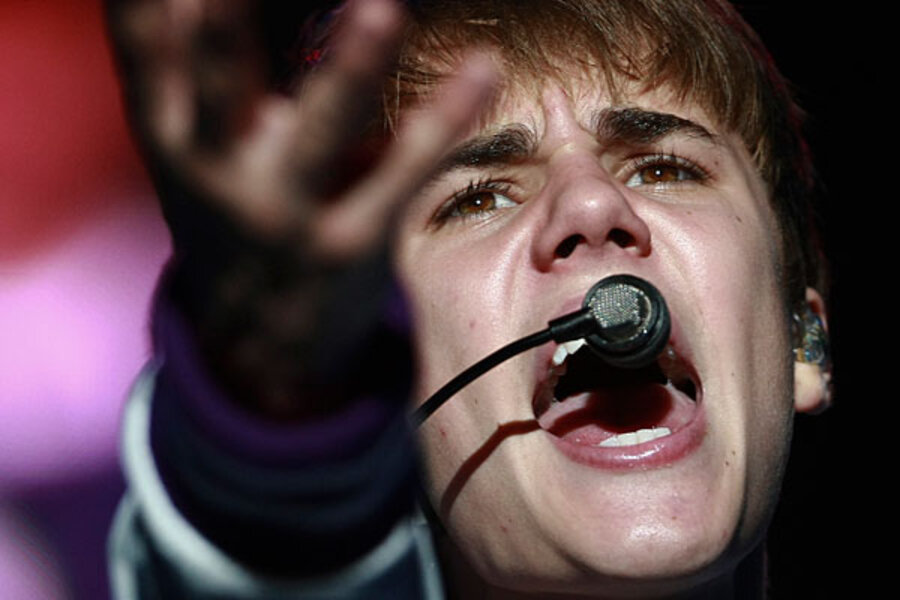

S.978: What Justin Bieber has to do with online streaming bill

Loading...

| Chicago

Is Justin Bieber facing hard time behind bars?

The teen star’s fate is up for debate, not in grade school cafeterias and strip malls, but in the US House of Representatives Wednesday, where lawmakers are expected to take up a bill that would punish the unauthorized online streaming of copyrighted content.

The proposed bill, titled the Commercial Felony Streaming Act, or S.978, is the latest chapter in the ongoing fight to protect major content providers including the motion-picture, recording, and television industries, which say they lose millions of dollars each year from illegal online video and audio streams on sites like YouTube.

Before his multiplatinum record sales, Mr. Bieber first gained notice as an online sensation, uploading videos of his interpretations of the pop hits of the day. Supporters say this makes him vulnerable to prosecution if the bill becomes law.

Technology advocacy organizations, such as Fight for the Future, say that the bill is too expansive and would criminalize what they categorize as harmless activities, such as videos of people “singing a song, dancing to background music, or posting videos of a kid’s school play.”

To make its point, Fight for the Future says Bieber would be facing five years in prison if the bill had been law when he made his first videos in his bedroom. An online petition is circulating via FreeBieber.org, a website the organization branded for its cause.

Lawmakers, however, say that the legislation is not intended to clamp down on fans, citing one basic fact: Uploading videos (which is what many people do) is not the same thing as streaming (some of which the bill would regulate). They also say the bill is only meant to address commercial bootleggers, who are intentionally and willfully distributing content for financial gain.

“This bill does not criminalize uploading videos to YouTube or streaming videos at home,” says Linden Zakula, communications director for Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D) of Minnesota, a co-sponsor of the bill along with Sens. Chris Coons (D) of Delaware and John Cornyn (R) of Texas.

Kevin Thompson, an Internet law and copyright attorney in Chicago, agrees that the bill’s language is intended to stop operators from hosting illegal streams of content that have a high price tag – such as movies, sports games, or concerts.

But, Mr. Thompson says, free-technology advocates have reason to worry because the bill’s broad language has “potential for misuse.”

“You could read it in such a way a prosecutor could decide that they could stretch it enough to make a case” to go after an individual suspected of piracy, he says.

The fight over this bill is part of a long line of strategies by media giants to protect their content from being infringed by online pirates.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act, a federal law enacted in 1998, put copyright owners, not service providers, in charge of policing the Internet for pirated content. The result: Up to now, media companies have been able to issue takedown requests to sites such as YouTube only when they notice piracy. The sheer volume of videos uploaded to the site each day – 48 hours of video each minute, according to the company – has driven media companies to push for more regulation.

One example: In July, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), which represents the major music companies, requested a subpoena to find out the IP address, among other information, of a YouTube user who illegally uploaded footage of a Britney Spears concert. The RIAA sought a similar subpoena to pursue users of Box.net, an online site that promotes content sharing, on the grounds they were illegally pirating content before its official release.

The RIAA, as well as the Motion Picture Association of America, Sony Pictures Entertainment, Viacom, NBCUniversal, Time Warner, and many other media giants and advocacy organizations representing the entertainment and sports industries are supporting the bill.

Those parties continue to protest a landmark 2010 federal court decision that found YouTube and its parent company, Google, not liable under federal copyright law for users who may be illegally sharing copyrighted content owned by Viacom. Viacom, which sought $1 billion in damages, returned to a New York court last week for an appeals hearing. The three-judge panel has not yet released its decision.

The bill up for debate in the House this week is not unexpected, says Corynne McSherry, intellectual property director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit digital-rights advocacy group based in San Francisco that is opposed to the legislation.

“Big media is losing in the civil courts so they said, ‘OK, we can’t win there because the law is not favoring us. So we’re going to go to Washington and see if we can win there, either by getting government to do the work for us or to pass legislation to give us new powers we didn’t have before,’ ” Ms. McSherry says.

“The reality is, a certain amount of infringement online is going to happen,” she says.