Why Republicans and Democrats see different things in an inauguration photo

Loading...

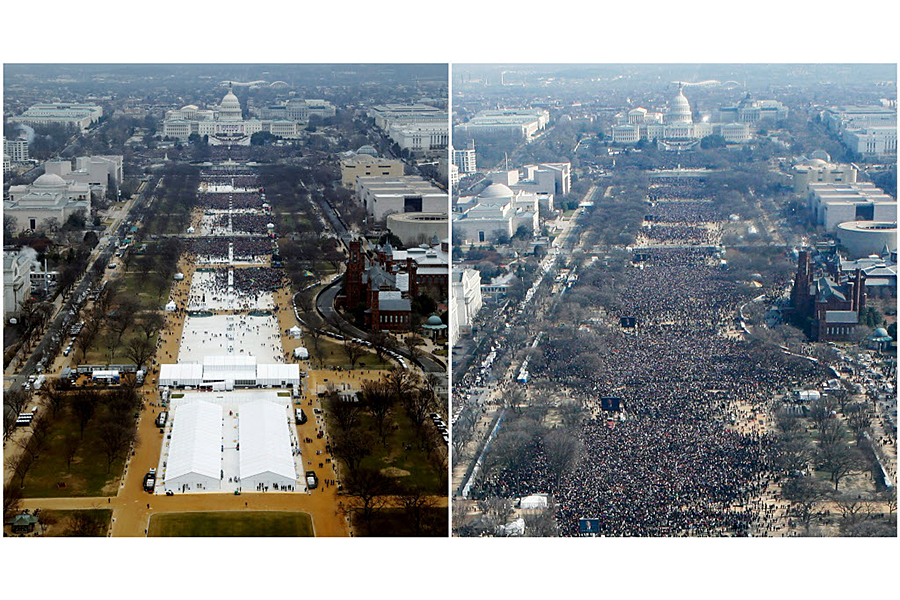

In an Inauguration Day picture, it appears crowd size is in the eye of the voter.

Those are the findings of a new study that asked Americans which of the two images – President Trump’s inauguration ceremony on Friday or Barack Obama’s 2009 swearing in – was better attended.

To the researchers, the answer was visibly clear. It was Mr. Obama’s inauguration ceremony in 2009. But one in seven Trump voters disagreed, a conclusion the researchers say could be the result of expressive responding, a kind of partisan cheerleading. In surveys, respondents sometimes provide answers that aren't factual, but that show support for a politician or party.

“Those people are basically saying, ‘I know there are not more people in that photo, but I also know the context of the question,' ” says Brian Schaffner, a political scientist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, who performed the study with Samantha Luks, managing director of scientific research for YouGov. “ 'I’m choosing to basically lie in order to support Trump.' ”

At first blush, the survey results offer a bleak view of partisan perceptions. Republicans and Democrats can’t even agree on photographic evidence, let alone policies, says Dr. Schaffner.

But the survey also offers insights into the motivations behind these factual disagreements. Political scientists and political psychologists agree the gears driving this discord are complex. They say it’s likely a combination of multiple factors: this partisan cheerleading, a mistrust of the media and how they present (or distort) facts, and a lack of knowledge about a political debate, but a willingness to provide an answer that supports your political team anyway.

In the survey, the 1,388 respondents, all American adults, were shown two pictures side-by-side. On the left was a view during Trump’s inauguration of the National Mall from the observation level near the top of the Washington Monument. On the right was a picture from the exact same spot eight years earlier, during Obama’s swearing in. The side-by-side was, of course, the image that went viral on Friday, and which the Trump administration said the next day was “deliberately false reporting” by the “dishonest media.”

The respondents, some of whom likely knew about the spat between Trump and the press, were asked on Sunday and Monday one of two questions about the photos. Half of respondents were asked which of the photographs was taken at Trump’s inauguration and which was taken at Obama’s. Forty-one percent of Trump voters gave the wrong answer, compared to 8 percent of Clinton voters, and 21 percent of nonvoters.

The other half of the survey participants were asked a simpler question: Which photo had more people? Fifteen percent of Trump voters, or about 1 in 7, gave the wrong answer, compared to 2 percent of Clinton voters and 3 percent of nonvoters.

Schaffner says Trump voters likely supplied the wrong answer for one or two reasons. Some might actually see more people in the 2017 photo. The other reason, he says, is expressive responding.

“In the question we asked, the truth was obvious and so right in front of people. They really couldn’t believe there were more people in the left-hand photo,” he says. “The only explanation is the 15 percent would have known what they’re saying is wrong. They have to choose what they’re saying anyway to support Trump.”

This political cheerleading applies to Democrats as much as to Republicans. In a 1988 survey, the University of Michigan’s American National Election Study, 30 percent of Democrats said unemployment worsened under the Ronald Reagan presidency. It didn’t. Unemployment actually decreased.

“In other words, when you ask people about the economy, the answers are less a statement of objectivity and more like what they’d say if you’d asked which pro football team was the best,” wrote Neil Irwin for the New York Times’s Upshot in 2014.

But Howard Lavine, a political psychologist at the University of Minnesota, says there’s another wrinkle in this discussion. In addition to answering out of ignorance or allegiance to your political team, respondents could also be confused between the verified facts about the crowds presented to them by the press and the unverified assertions presented by the Trump administration.

“Now, I think we’re entering a realm, sadly, in which people really are confused,” says Dr. Lavine, director of the university’s Center for the Study of Political Psychology, and who was not involved in the study. “Populist-oriented Republicans have been saying for quite some time, ‘Don’t trust the mainstream media. They’re lying to you’…It’s possible that [respondents] believe that that’s true – that they’re being lied to. What that amounts to, then, is that they actually believe the response they’re giving you.”

While the pictures of the two inaugurations went viral, they were snapped by only a few news outlets. According to the Reuters editor in charge of his outlet’s photo, there were three camera operators on the observation level of the Washington Monument. One was from Reuters, one from CBS, and one from the National Park Service. PBS “NewsHour” also posted a time-lapse video of the crowd throughout Inauguration Day.

But Trump said at CIA headquarters on Saturday that the “dishonest media” showed pictures of empty spaces at the mall, while White House press secretary Sean Spicer accused some of the media of “deliberately false reporting.”

In addition to a growing body of research that has shown politicians and political elites can effectively spread conspiracy theories among supporters, Trump and Mr. Spicer’s accusations come as trust in the mainstream media is at an all-time low.

How do these two images, then, fit into the bigger picture of the partisan divide?

It’s not good, say political science and psychology experts. Patrick Miller, a political scientist at the University of Kansas, also not involved in the study, says it shows how Democrats and Republicans live in two completely different worlds, with different news and different facts. Dr. Lavine adds voters have become increasingly less motivated by getting behind policies and politics that are good for them, and more about whether their team is winning or losing.

But he adds that in the 1950s, the American Political Science Association bemoaned the opposite, that parties were too non-ideological. There were a great many conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans, they said. Today, it appears the the opposite is true.