Building takeovers push campus protests into volatile new phase

Loading...

The protest movement roiling college campuses across the United States appeared to enter a more dangerous phase Tuesday, as student demonstrators who had barricaded themselves inside a hall at Columbia University were arrested overnight by police in riot gear, and protesters on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict clashed violently at the University of California, Los Angeles.

By moving from tents on a lawn to inside a building the students at Columbia sharply escalated the crisis. In parallel moves this week, protesters have also occupied buildings at some other U.S. campuses.

Why We Wrote This

For protesters, the tactic of occupying buildings at Columbia University and beyond has historical echoes. But it also creates new risks for campuses and for the protesters themselves.

And while some experts say the increased pressure could still ultimately help the protesters secure some of their demands or gain more public support, in the short term it seems to have backfired, shifting more attention to their tactics than to their cause.

On Tuesday, a Columbia University spokesperson said the students involved faced expulsion for their actions. The tactic of occupying university property and refusing to leave until demands are met evokes the symbolism of past protests at Columbia and other campuses, events that have over time become celebrated as progressive landmarks by the same universities.

The protest movement roiling college campuses across the United States appeared to enter a more dangerous phase Tuesday, as student demonstrators who had barricaded themselves inside a hall at Columbia University were arrested overnight by police in riot gear, and protesters on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict clashed violently at the University of California, Los Angeles.

By moving from tents on a lawn to inside a building the students at Columbia sharply escalated the crisis. In parallel moves this week, protesters have also occupied buildings at some other U.S. campuses.

And while some experts say the increased pressure could still ultimately help the protesters secure some of their demands or gain more public support, in the short term it seems to have backfired, shifting more attention to their tactics than to their cause.

Why We Wrote This

For protesters, the tactic of occupying buildings at Columbia University and beyond has historical echoes. But it also creates new risks for campuses and for the protesters themselves.

On Tuesday, a Columbia University spokesperson said the students involved faced expulsion for their actions. The encampment has been cleared, and Columbia’s embattled president, Minouche Shafik, has asked New York police to remain on campus through May 17.

The tactic of occupying university property and refusing to leave until demands are met evokes the symbolism of past protests at Columbia and other campuses, events that have over time become celebrated as progressive landmarks by the same universities. At Columbia, the anti-war protests of 1968, during which five buildings were occupied for a week resulting in chaotic mass arrests, have been burnished into memory for students and faculty.

As in the 1960s, the demands and tactics at Columbia, with its “Gaza solidarity encampment” on the main lawn, inspired students at other colleges and universities, whether as coordinated actions or simply as copycats seeking to escalate.

Buildings seized on other campuses

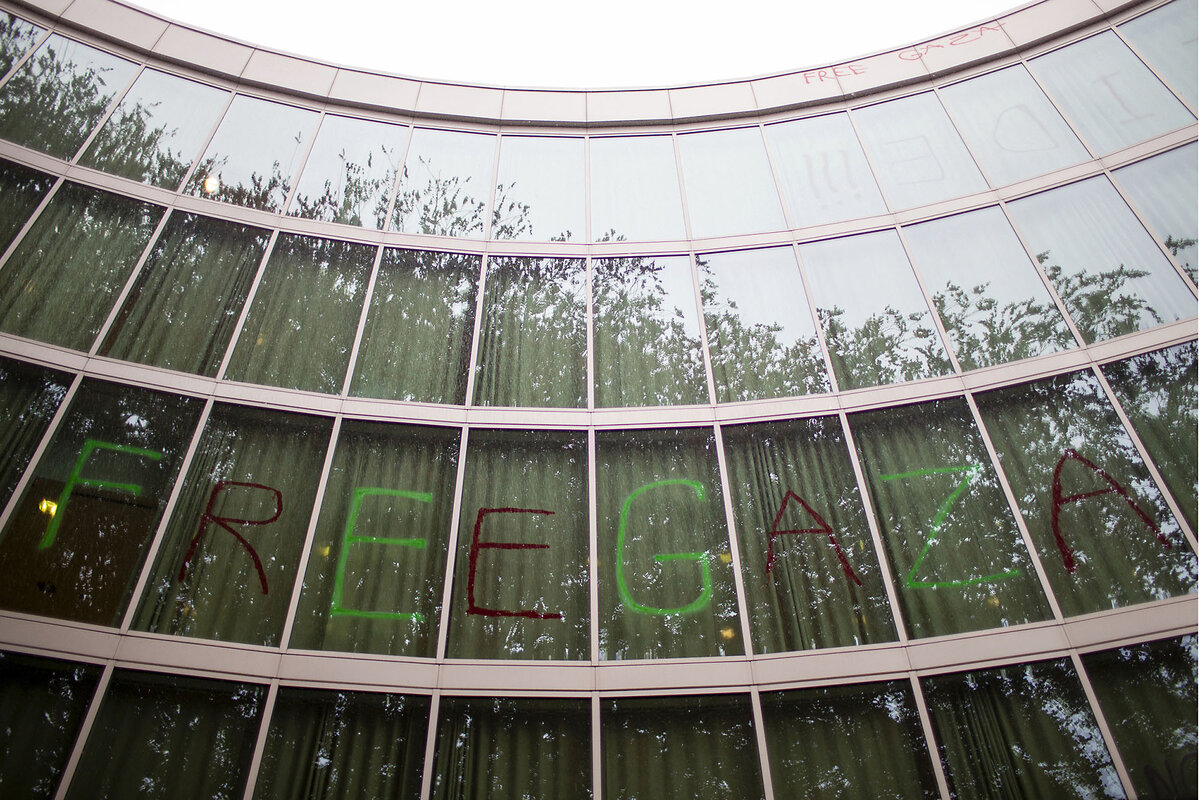

In Portland, Oregon, between 50 and 75 pro-Palestinian students occupied a library at Portland State University late Monday. University officials have asked city police to intervene, CNN reported. At Princeton in New Jersey, a group of protesters briefly occupied a graduate-school building overnight; police later arrested 13 people, mostly students, who have been barred from campus. Students also took over a building at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque but were dispersed early Tuesday morning by state and campus police.

Earlier Tuesday morning, police retook two buildings at California State Polytechnic in Humboldt that students had occupied since last week, leading administrators to close the campus. Police arrested 35 people. One of the buildings had been renamed “Intifada Hall” by the protesters.

The White House released a statement Tuesday saying that President Joe Biden “condemns the use of the term ‘intifada,’ as he has the other tragic and dangerous hate speech displayed in recent days. President Biden respects the right to free expression, but protests must be peaceful and lawful. Forcibly taking over buildings is not peaceful – it is wrong. And hate speech and hate symbols have no place in America.”

At Columbia, protesters hung a sign reading “intifada” outside Hamilton Hall, the occupied building, which was one of the buildings seized in 1968. The building was occupied late Monday night by a breakaway group from the Gaza encampment, after an afternoon deadline passed for students to disband their camp or face disciplinary measures. The numbers inside Hamilton appeared to grow Tuesday as fewer remained at the camp. Protesters have been calling for the university to divest from Israel-related assets and to repeal the suspensions of students arrested on April 18, when over 100 were taken into custody.

Those arrests by the New York Police Department were orderly; leaders had prepared students for detention, advising them to not resist and to only speak with a lawyer present. But the occupation of a building seemed to herald a more chaotic and violent phase.

While Princeton was quick to call in police officers to end its overnight occupation, administrators at Columbia did not respond as quickly after the fallout from the April 18 arrests, which marked the first time the NYPD has been summoned to the campus since 1968. The practical challenge also appeared greater as Hamilton Hall swelled with protesters, and a phalanx of TV cameras filmed from outside the shuttered campus gates.

“Civil disobedience consists of demonstrating why a rule isn’t a good rule,” says Lara Schwartz, director of the Project on Civic Discourse at American University. She adds, “We are seeing students saying, ‘We’re going to be in places you’ve told us we shouldn’t. Because your attempts to suppress our message are wrong.’”

The role of Columbia faculty has also complicated efforts to end the occupation. Last week the university senate voted in favor of an investigation into how the leadership had responded to protests and whether it had breached due process for faculty accused of violating codes. Some faculty members have taken positions in favor of protesters, including guarding access to their camp.

How war in Gaza resonates on U.S. campuses

Protests and counterprotests have been held at Columbia since the days after Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7 in what was the country’s deadliest attack since its founding in 1948. Pro-Palestinian demonstrations have grown in size as Israel’s response to the attack – and to Hamas’ taking of hundreds of Israeli and foreign hostages – has decimated Gaza and killed tens of thousands of civilians, a response undergirded by U.S. military aid.

Some Jews at Columbia say they no longer feel safe on campus because of antisemitic threats and slogans from protesters, whose ranks include Jews who say their target is Israel and its leaders, not Jews as a group. A lawyer has filed a class action suit against Columbia over the displacement of Jewish students.

Although only a small minority of college students are protesting, young people ages 18 to 29 view Palestinians more positively in general. In a recent Pew Research Center poll, they were the one age group in which a higher share viewed Palestinians favorably (60%) than viewed Israelis favorably (46%).

Occupations and sit-ins have a long history on U.S. campuses. Some have been effective at forcing change on administrators. In 2001, students occupied a university hall in Harvard Yard for three weeks to protest low wages paid to campus staff, including janitors and caterers. The university eventually agreed to raise their hourly wages.

One prospect for universities is that crackdowns could expand the ranks of student protesters – not necessarily by occupying buildings but being engaged in some way.

“We ... have seen that institutions engaging in tactics where their action is to suppress student speech or punish it, or punish student groups or ban student groups, have seen an increase in students saying, ‘Well, we’re going to use our voices more. Our voices are going to get bigger,’” says Ms. Schwartz at American University.

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to reflect news developments.