After the tornadoes: Rebuilding a campus, piece by piece

| Jackson, Tenn.

It's a cold, blustery morning here in western Tennessee, the sun high and bright, the sky a preternatural robin's-egg blue. The kind of halcyon day reserved for picture postcards. The kind of perfect day depicted in glossy campus brochures.

An entrance sign to Union University blinks a cheerful welcome: "Get to know Union." Just beyond, less than 1,000 feet away, lies a cruel irony – Union's heart and soul laid bare, the lives of its students revealed in rainbow-hued paper and clothing clinging to winter-bare trees.

Nearly a week has passed since last Tuesday's storm system ripped through the mid-South, leaving a deadly trail of destruction across five states, including Tennessee, where the Baptist-based liberal arts school took a direct hit from an EF-4 tornado with winds topping 200 m.p.h. In awed voices, students run through the numbers and count God's blessings: 3,200 students, 1,200 on campus when it struck, 13 trapped, 51 injured – no fatalities. The buildings can be replaced, and many will have to be – 40 percent of the dorms were destroyed and 32 of the 33 buildings dotting the 290-acre campus sustained an estimated $47 million in damage.

It's the third time in less than a decade tornadoes have left Union picking up the pieces and trying to move forward. But the air is light today as students gather in the sunny yellow rooms of the Chi Omega house, now a makeshift command post. The shock is beginning to wear away, leaving an appreciation for life's smaller pleasures.

For Renée Jones, assistant director of recruitment, a mop is the best thing she's seen all week. "This is fabulous," she says, dumping bottled water on the muddy linoleum and swabbing it to a dull shine. So much of the campus was atomized by the tornado that it's impossible for students and volunteers to keep their shoes clean as they trudge back and forth, trying to salvage whatever they can from the destruction.

Ms. Jones says it's not about cleanliness but a deeper mission the faculty shares – providing calm and comfort amid chaos. While the university remains in "essentialist" mode, addressing fundamentals like housing and coursework, the staff slowly shifts from survival to caretaking, facing a new challenge – how to hold a campus community together when the campus is gone and the community is spread in hotels and homes across the city.

•••

David Dockery perches on the edge of a chair, elbows on knees, a red Union jacket warming his drawn face and tired eyes. He was on campus when the tornado struck around 7 p.m., meeting with two deans to discuss what's always on his mind – Union's future. Since he became president in 1995, Dr. Dockery has pushed an ambitious 25-year master plan. He stares at the floor as he admits the plan was almost halfway complete, with $60 million in renovations over the past decade. This tornado was "15 times" worse than the previous two, he says, made more cruel by its impact on the students' personal lives. Since then, his only thought has been how to give back what was taken – clothing, papers, a place to live, an education.

"I made as many decisions in the first 100 hours as I normally make in 100 days," he says, rubbing his eyes. He's slept only 16 hours in the past week. It's not only the tangibles keeping him awake – how to retrieve student valuables, resume classes, provide textbooks and computers and everything required to run a campus – it's also the intangibles.

The college had to cancel an annual conference for high school and middle school students, along with revenue-generating summer sports camps, a worship symposium, and a Valentine's Day banquet for west Tennessee pastors. The school's 62 clubs, from wrestling to Bible study, must get back up and running, offering small communities where students can feel a natural affinity and the healing balm of the Union spirit.

The basketball team is borrowing another school's gym – their own filled with bags of belongings salvaged from the rubble and neatly tagged. Dockery hopes to have the athletes playing at home by Feb. 21. And then there are things like driver's licenses, bank cards, and passports. Little pieces of plastic so necessary to function in daily life.

For a moment, Dockery seems bowed by the sheer enormity, then he squares his shoulders and a faint smile lights his eyes. There were no deaths, and that's something. A thousand people volunteered to help the very next day, and that's something, too. Union will rebuild what was destroyed and resume the master plan, more slowly perhaps, but always, always moving forward. "I don't think we've lost hope, and I don't think we're Pollyannaish," he says. "Our deep faith will carry us through."

•••

At Duncan Hall, a girls' dorm, social work professor Kristie Holmes is on a mission of her own – salvaging something, anything, from each student's room. She's young, barely older than the students she teaches, and this is her first year as a professor. She doesn't have to be here today, or at least her job doesn't require it, but like the colleagues who dig alongside her, no other task is more important.

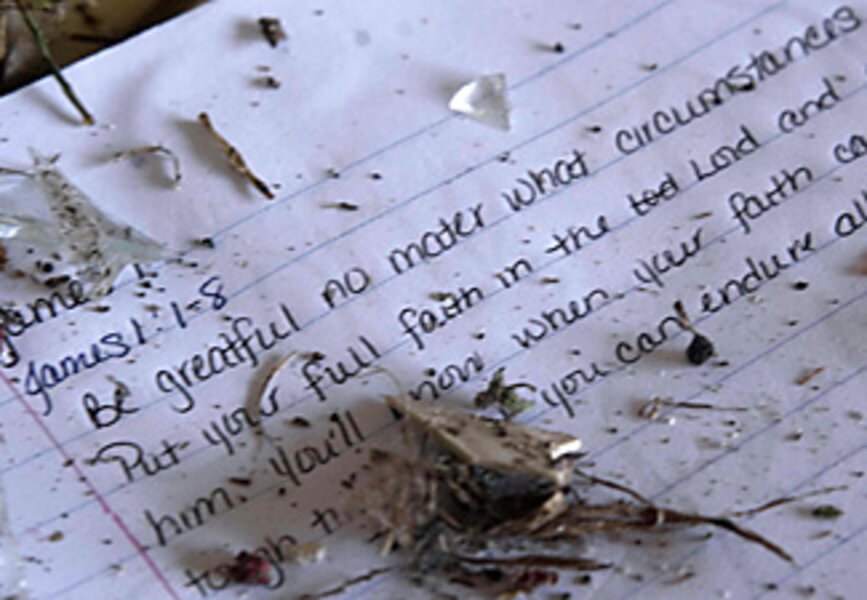

The wind whips her blond pigtails, chafing her cheeks as she dons leather work gloves. She pauses at a broken window and peers inside. Workers marked this room "done," condemning it and moving on, but they're men, she says. They only retrieved electronics. Women want other things – letters, teddy bears, diaries, "things I'd be really happy to see." She picks over mud-covered clothes and DVDs, rifles though drawers filled with cosmetics, and scans sagging bookshelves.

"One of the journals I found was really wet," she says, separating a pile of sodden greeting cards. "It started out saying, 'I don't know how I would have gotten through this day without this journal.' It's a reminder of where that girl's been, and it's important to get it back to her."

In some cases, the rooms were swept clean by the storm's fury, and she has to search harder. "Even if it's just an umbrella, at least that's something," she says, carefully bagging one.

Back at the Chi Omega house, accounting major Sherita Smith chatters happily as she clings to her mother, her mirth belying the terror she experienced as she and her roommates stepped from the bathroom where they'd taken shelter, only to find themselves outside, the rest of their apartment demolished. She's heard someone found her belongings and she's hoping two things were saved – a red and white stuffed monkey and a folder. She's an aspiring writer, and the slim binder is filled with poetry, short stories, and essays.

Her cellphone is gone, along with the phone numbers of her friends. The Commons building, where she used to watch movies on Saturday nights, is gone, too. Now, like her classmates, she just wants the scraps of paper that tell who she is and what she hopes to become.

It's a simple want, a basic need. But at Union University, where the familiar is now the hauntingly unfamiliar, it's everything. A symbol of hope. A marker of faith.