BP oil spill imperils Cajun culture

Loading...

| Chauvin, La.

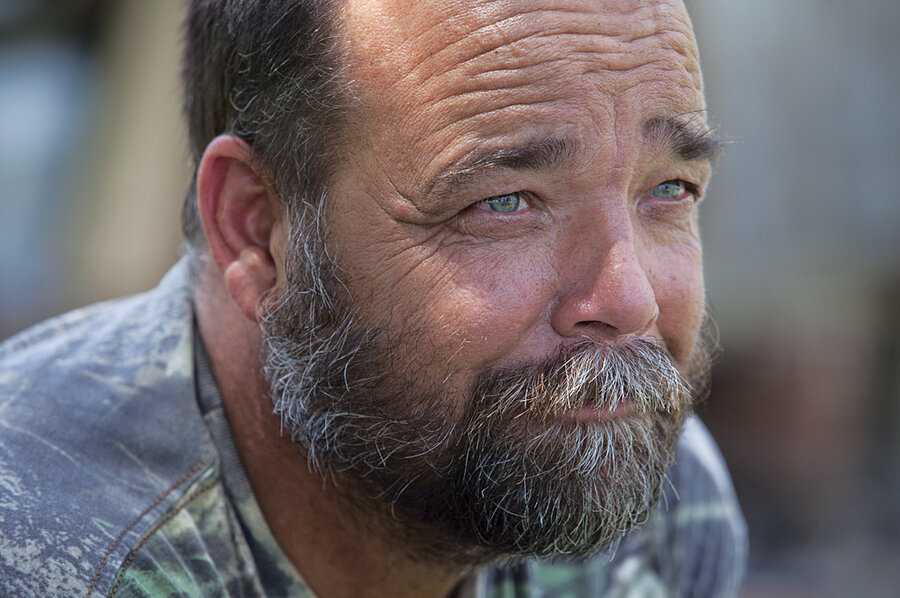

Darren Martin is a third-generation shrimp boat operator – and as far as he knows fishing may be in his blood even beyond that. His family has been rooted in the small winding bayous of southwest Louisiana since the 1700s, when the Cajuns of French descent were exiled by the British from their native Acadia, now eastern Canada.

With such a rich connection to the land and water here, it would only be natural for Mr. Martin to want his teenage son to continue the family trade – pulling up seafood from the Gulf of Mexico and selling it at his family's stand across from their ancestral home in this quiet town of just over 3,000 people.

Yet after years of hardships ranging from hurricanes to floods to shrinking prices and now an oil spill, Martin has determined that commercial fishing, a cornerstone of Cajun identity, is dying and that "this generation," his own, "is going to be the last."

"Why am I still here?" he asks. "I don't want my son to do this. But I can't keep him away."

There are countless casualties of the Deepwater Horizon explosion that sent oil spewing into the Gulf in late April, but how it is affecting Cajuns here is particularly profound: It threatens not just to take away their livelihoods, but also to grind down an identity of independence and self-reliance that was established when their ancestors were forced to find ways to survive in an environment that many considered uninhabitable.

Cajuns interviewed for this story all expressed loyalty to the land of their ancestors and said that those who traveled outside the state always find a reason to return. Many expressed the belief that their way of life would not work outside the region and said that when they do travel, they no longer feel Cajun, but like just another assimilated American.

"What are they going to do in another place? What they do is what their families have been doing forever," says Ann Savoy, an author and Cajun musician who lives outside Eunice, La.

Ms. Savoy says that central to understanding the Cajun culture is knowing that isolation. "The Cajuns see themselves as another culture and not so much Americans. They love this freedom that they wouldn't have in other places. Because when you live in a swamp, you can do anything, all the time," she says.

Savoy says Cajun identity is so distinct that each town often has its own cuisine, musical style, and dialect. The cultural markers are a result of families staying put for generations, which is what makes these communities resilient in the face of nature's hardships and resistant to change.

Tracking how many Cajuns live in the region is difficult, says James Wilson, assistant director of the Center for Louisiana Studies at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. He estimates that about 400,000 people identify themselves as Cajun, but the term has broadened over the past century to include many who may not be direct descendants of the Acadians but may have married one, or those who simply came from families that moved to the region 100 years ago and took to the culture.

The culture was under threat in the early- to mid-20th century when Americanization efforts barred the speaking of Cajun French in schools. That was remedied in a renaissance period in the 1970s and '80s when the language, music, handicrafts, and storytelling was embraced and the Cajun stigma faded. "People started to self-identify with the term more," says Mr. Wilson.

"I love it down here. There's no place I want to go," says Lyle Lecompte, a shrimper since 1978 who recalls a childhood splashing in the waters of Little Calliou Bayou alongside alligators – "Alligators don't eat Cajuns, they're scared of them," he says – and almost two dozen hurricane evacuations. Those consisted of strolling over to the family boat.

But uncertainty about the future of the Cajuns' livelihood, and thus their identity, is creating what Savoy calls "a state of fear." The impact of the spill, as well as the tough regional economy, is once again testing their trademark resilience.

"It's either work for BP or find somewhere else," says Jerome Picou. "I don't want to do it. I want to shrimp."

Right now, that's difficult. Of the 640 miles of oiled coast, 362 miles are in Louisiana. To date, 57,539 square miles of federal Gulf waters, or 24 percent, remain closed to fishing. Scientists say the oil threatens commercial fishing by potentially preventing the growth of algae and other microscopic life that feeds the upper food chain, wiping out life on the seabed, such as crabs and oysters.

Because the volume of oil spilled is unprecedented, Myron Fischer, director of the fisheries research lab at Grand Isle State Park in Grand Isle, La., says it is uncertain how severe the damage will be on local waters. "Throughout history we have had various types of small tragedies: freezes, pollutants. But we've never experienced a large case of oil intrusion into estuarine areas," says Mr. Fischer. "We don't know how the oil is going to be absorbed by the vegetation, how's it going to disperse. It's a new challenge for all academic science."

According to BP, about 3,000 local vessels are being used to skim the oil and maintain booms. Mr. Lecompte is opting not to work as a BP oil skimmer because he worries about the chemical dispersants BP has been using to mitigate the oil. "I don't want to play in that oil. That ain't nice," he says. So, along with Mr. Picou, he spreads his nets along the bayou's grassy banks, cleans them, and waits. "I am ready to go shrimping anytime. When they want to open [closed fishing waters], let me know," he says.

The oil spill is particularly harsh because it follows decades of coastal erosion. According to the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, Louisiana has lost about 20 percent of its wetlands over the past century, or some 2,000 square miles. Today the coast is shrinking by almost 30 square miles each year.

Combined, the erosion problem and oil spill is "a two-headed monster" for Cajuns, says Jennifer Ritter, assistant director at the Center for Cultural and Eco-tourism at the University of Louisiana in Lafayette. There are not yet signs of a Cajun migration from the region, but Ms. Ritter speculates that if the seafood industry dries up, they will likely demonstrate the resourcefulness of their ancestors.

"They can create a livelihood in one fashion or another, from farming the land on top or grazing cattle or digging shallow ponds for crawfish or to grow rice. It's a very simple people we're talking about. They're able to find what they need where they live," she says.

Interviews with many Cajuns in this area all circle back to the same theme: an undeniable attraction to water and the area's natural beauty.

Tommy Thibodeaux, who is now skimming oil for BP, says he tried for years to turn away from his ancestral past, first working for Texaco and then, after being laid off, running a landscaping business for 10 years. He now mans his own shrimp boat, docked near his childhood home.

"I live on the water. I was brought up in it," he says. "You kind of have it in your blood."