America's new culinary renaissance

Loading...

| Chicago

The clumps of cauliflower clouds suddenly part and a wash of sunshine engulfs the expectant crowd in an outdoor amphitheater here. It's a setting that would be spectacular even without the solar arrival: a fruit and vegetable garden on an island in a small lake in the Chicago Botanic Garden, where beds of alfalfa and garlic grow in sculptured rows.

The crowd of at least 150 people eagerly awaits the day's entertainment. Three rows from the front, a woman in black with sunglasses the size of headlights arrives early and sits between two seats saved with terra-cotta pots. Nearby, a young man checks the settings on his impressive-looking camera. In the front row, a retired physician passes the time with a thick book of crossword puzzles, glancing up occasionally at the stage.

Finally, a host introduces the featured act, Roger Waysok, who strides forward and, after a burst of applause, begins his performance ... creating a barley, feta, and tomato salad with fresh mint.

"All the fresh ingredients in here, I am passionate about," says Mr. Waysok, the executive chef of Chicago's South Water Kitchen restaurant, his knife poised over a red onion.

The chef series that runs from May to October at the botanical garden here draws hundreds of people each week. But it could be a demonstration held in almost any venue in America. In a land of fads and social movements, from fitness to feminism, now comes a new one – food.

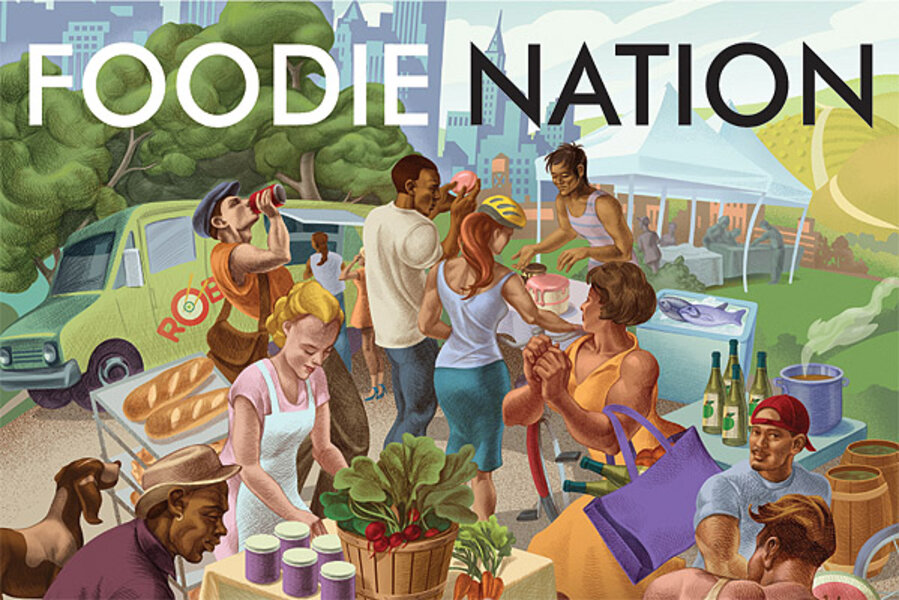

America is, quite simply, fascinated by food in a way it never has been. We have become a nation of "foodies" who celebrate, debate, pursue, and show off knowledge of what we eat and how to make it. We're watching food shows endlessly on TV. We're enrolling in cooking classes in record numbers. We're loading our shelves with cookbooks and our e-mail with recipes for salt-crusted snapper. Our new celebrities aren't LeBron James or Julia Roberts. They're Bobby Flay and Southern food queen Paula Deen. In short, we have become something of a Sous-Chef Nation.

"We are witnessing the Italian Renaissance in food … an intellectual elevation that is turned into something durable through media," says Krishnendu Ray, a food and nutrition expert at New York University. "The world of food today is exactly how the world of literature and painting evolved."

Really – nouvelle meatloaf as the Mona Lisa?

Not exactly. What he means is that painting started with artists producing images on canvas. Then people began buying paintings, critics began critiquing them, and soon an entire culture had sprung up around art. Today food is creating a similar buzz – people, young and old alike, are trying to become Botticellis of braised short ribs and then celebrating it with friends, reveling in the experience of mastering the art of cumin.

Cooking, in other words, is no longer just something your mother does to put dinner on the table. It's a vehicle to express creativity, forge social connections, articulate what we have learned from other cultures, and in some cases save the environment.

"Food has become an entire lifestyle," says author Christopher Powell, who helped launch the kitchen retailer icon Williams-Sonoma. "It's no longer just about preparation or consumption.

The transformation of food from kitchen to cultural phenomenon is evident everywhere. Farmers' markets and gourmet food trucks have proliferated across the country. Urban hipsters now preserve their own jams. Suburbanites are raising chickens so they can have fresh eggs. The most mundane fare – from hamburgers to cupcakes – has been turned into haute cuisine. Has anyone not had French fries made in duck fat yet? Cuisine is even popular on the big screen, from the dramatic ("Julie & Julia") to the animated ("Ratatouille").

Roger Hand, a retired doctor who attends the botanical chef series here every week, recounts how he recently attended a Shakespearean play and was surprised to find Elizabethan-Era recipes on sale in the lobby. "Going to see 'As You Like It,' I didn't think I'd come home with a cookbook," he says.

What's behind the new food culture, and are Americans really eating better as a result?

* * *

On a Friday evening in Cambridge, Mass., 10 people listen intently to Dave Ramsey, an instructor at the Cambridge School of Culinary Arts, explain the basics of using an industrial kitchen: Don't touch the outsides of the ovens (they are hot); carry knives pointed downward at all times; and most of all – have fun. The group is made up of friends, spouses, and soon-to-be-marrieds. It's a Spanish cooking class for couples.

Within minutes, the students, wrapped in white aprons, scurry off to separate workstations. Half the room begins chopping garlic, bell peppers, zucchini, and parsley, as well as slicing baguettes, zesting lemons, and peeling potatoes. The other half works over a bank of stainless-steel stoves. Together, the group is creating a multicourse Spanish meal, from gazpacho Andaluz to crema Catalana, in three hours.

For one of the couples, Peter and Trese Ainsworth of Needham, Mass., this is their first cooking class. Mr. Ainsworth, a lawyer, professes that he is a relatively new convert to the kitchen – but a passionate one. When a favorite Italian restaurant in his neighborhood, Sweet Basil, published a cookbook a few years ago, he felt as if he had been given the "keys to the universe." He taught himself to make stocks and sauces. Now he prepares a big family meal every Sunday.

It doesn't end there. He built a raised-bed garden in order to grow his own tomatoes, herbs, and carrots, and regularly watches the Food Network with his two teenage daughters. "I look forward to cooking. It relaxes me," he says.

His rationale for taking up a chef's knife after wrestling with legal briefs all day explains why many people are spending more time in the kitchen: It's something that virtually anyone can do – and it's satisfying. It is a form of self-expression and status, entertainment and education.

In an age of a service economy and pervasive cubicle culture, many people who spend a lot of time glaring at com-puters find cooking a way to create something tangible. In that sense, the interest in cooking parallels the rise of other "hands on" movements that attempt to balance the virtual world with throwback skills, such as laying your own sheetrock and knitting.

Some people, too, are attracted to cooking as a sort of rebellion against the McDonaldization of America and what they see as the tasteless, processed products of an industrialized food system. "I live alone and can't stand prepared food, so I've learned to cook fairly elaborately for one," says Mr. Hand, whose repertoire includes Wiener schnitzel, polenta, and bouillabaisse. "It's an art."

Like any art, it takes considerable skills to master, which is where the guidance and ingredients of others comes in. In the past year, sales of "cooking/entertainment" books have jumped 4 percent in the United States, while all other categories of adult nonfiction dropped 2 percent, reports Nielsen BookScan, which compiles statistics for the publishing industry.

Classes for both the hobbyist and serious chef are thriving. Enrollment in the gastronomy program at Boston University has tripled in the past three years. "A lot of them don't want to go to culinary school and become a line cook, but they want to do something [meaningful] with food and education," says Rachel Black, the coordinator of the program, which was started by Julia Child and Jacques Pépin in the 1980s.

Le Cordon Bleu, which operates 17 culinary institutes in the US, reported a 20 percent increase in students in 2010. In San Francisco, a venture called Hands On Gourmet, which teaches clients to cook through private and corporate parties, now reaches almost 5,000 people a year.

"A lot of people who come through our doors don't know how to cook, but most people want to learn," says chef Stephen Gibbs, who runs Hands On Gourmet. "When they learn how to make their own Indian or Thai curries ... they say, 'holy moley, I just made that?' They are flabbergasted."

The proliferation of new media is adding to the foodie culture. No longer do you have to thumb through some Italian cookbook you may or may not have to find the best way to make shrimp fra diavolo. You can find as many recipes as you want – for the novice or gourmand – with the click of a mouse. Want to know something as mundane as how long it takes to boil an egg? Type the query into Google's search engine and you'll get 40,600,000 suggestions in less than one second.

Something more obscure? Try vichyssoise, a seasonal soup, usually served cold, that is made of scallions or leeks, potatoes, and cream. An online search will yield 640,000 hits, including a debate over the soup's origin (best guess: either a French chef or one at New York's Ritz Carlton in the early 1900s).

If finding a recipe and a little sociology behind it isn't enough, you can always register with Foodista.com, an online cooking encyclopedia, where you can post your own recipes and have others rate – or edit – them. Foodista now has 20,000 registered users, 110,000 Twitter followers, and 25,000 Facebook fans.

"People have always talked about food," says NYU's Professor Ray. "The difference is, with [the proliferation of] new media, the conversation is now reaching everyone all the time."

And it isn't just talking. The ease of publishing has given rise to legions of food bloggers who swap not only favorite recipes but also personal narratives centered around their creations in the kitchen. Many digital cameras now include a "food setting" that enables online foodies to capture the wisp of steam, the sheen of oil, and the flecks of pepper on their plate of grilled asparagus, all in high focus.

"We connect so many emotions and memories around food," says Elisa Camahort Page, cofounder and chief operating officer of BlogHer, a blog platform whose food-related pages receive 11 million unique visitors a month. "[Through blogs] you learn from places, people, cultures, and classes that you might have never encountered in regular life."

Yet the biggest driver of America's current fascination with food is not coming from new media but a decidedly old one – television. Two Food Network channels now pump out programming 24 hours a day, producing a mind-numbing 190 shows. Other series can be found all over the clicker, from Bravo's popular "Top Chef Masters," to efforts by the bigger networks to tap into the food craze – with decidedly mixed success – with shows such as "Jamie Oliver's Food Revolution" (ABC), "Hell's Kitchen" (Fox), and "America's Next Great Restaurant" (which NBC is dropping after only one season).

None of these, mind you, is Julia Child showing you how to make sole bonne femme in a harpsichord voice. The emphasis today is on entertainment and, increasingly, sport. Series such as "Iron Chef" and "Chopped" pit chefs against chefs in a battle of the clock and creativity in using a "secret" ingredient or everyday food items. "Best in Smoke" is a similar joust among barbecue pitmasters. Even bakers clash pans in "Cupcake Wars" and "Last Cake Standing." It's all a bit like the Red Sox versus the Yankees with oven instead of baseball mitts.

"So much food TV is really sports – watching people do awesome things," says Ray.

Many people are tuning in. Merrill Feather of Cambridge, Mass., and her friends love to watch Paula Deen, "Diners, Drive-ins and Dives," and "The Great Food Truck Race." For the past two years, she and her fiancé, Keith Richey, have hosted Oscar-watching parties with movie-themed dishes such as "Tuna Avatartar," "The King's Peach Cobbler," and "True Grits." Last year a group of them even created a fantasy draft for "Top Chef."

Food aficionados insist all this is creating a generation of people more literate about cooking and cuisine. "People 'get' food now – they understand the value and they want to know more," says Kay Logsdon, editor in chief of the FoodChannel.com, an Internet-based cooking resource. "People are looking for information to 'help make me a better cook, give me tips, answer my in-depth questions, give me direct access to a chef.' "

It has also made cooking glamorous. Cooks used to toil in anonymity behind portal-windowed kitchen doors. Now many of them have become celebrities, spending as much time on talk shows and in TV commercials as they do on menus (or, in the case of Paula Deen, being grand marshal of the most recent Rose Parade in January).

Even more workaday chefs are being asked to come out from behind their colanders. People want to know their lineage – where they've worked and for whom. They've become public figures as much as purveyors of parsley.

"Before if you wanted to be a chef, you had to know how to cut and cook," says Waysok, the chef putting on the demonstration at Chicago's botanical garden. "Now all of sudden you have to have a personality and talk to people, too."

* * *

While a nation of foodies may seem like a recent phenomenon, many see it evolving out of a much deeper food revolution. James Beard introduced the American public to the idea that food could be "gourmet" in the 1950s. The indomitable Ms. Child began tutoring us on French cooking in the 1960s.

Alice Waters – the grand dame of the "slow food" movement – started declaring the benefits of locally grown goods in Berkeley, Calif., in the 1970s. Her work continues to be influential today, including in the efforts of first lady Michelle Obama to bring healthy foods to inner-city communities.

The "eat fresh" movement, in turn, has contributed to making food more than something you just consume at the dinner table. It has elevated it to a lifestyle. More people now grow their own herbs and vegetables, whether in rooftop gardens or in backyard plots such as Mr. Ainsworth's in Needham. Farmers' markets are flourishing. Last year, more than 6,100 of them operated across the country, according to the US Department of Agriculture – a 16 percent increase over the year before.

"Locally grown food" and "in season" ingredients are the rage among restaurants in every region, too. Some of them even host "farm to table" events where patrons can meet the farmer who grew the beets marinating in vinaigrette on their salad plate. The idea is to create not just a meal but an experience. (A "farm dinner" held at the Chicago Botanic Garden, as a fundraiser, costs $200 a person.)

Ana Sortun and her husband, Chris Kurth, epitomize the growing trend. She is the head chef and owner of a restaurant and bakery in Cambridge, Mass. The Eastern Mediterranean cuisine she serves at Oleana has earned her a James Beard award and a spot on "Top Chef Masters." In addition to writing a cookbook, she and her staff offer cooking and baking classes at Sofra, her bakery.

The flavors and spices that form the basis of her cuisine are enhanced by the fresh produce she gets delivered each day from a familiar source – her husband. He runs a 50-acre organic plot, Siena Farms, which produces enough carrots, radishes, and other food to supply restaurants, farm stands, and a 300-member community agricultural group in the Boston area. Theirs is a marriage of local produce and worldly flavors. "We are ingredient seekers," says Ms. Sortun. "Forget that we love farmers and it's good for the environment and all that stuff. The main reason we [use locally grown food] is because it tastes better."

* * *

All of which raises a basic question: Is America really advancing as a culinary – and eating – culture as a result of the latest fascination with food? Probably yes and no.

Certainly not everyone is turning into an Emeril Lagasse. Americans still spend 49 percent of their food budgets on eating out, estimates the National Restaurant Association, an unhealthy portion of which goes toward Whoppers and Big Macs.

Moreover, fixing a good meal at home, or getting one in a restaurant – particularly if using fresh, locally grown ingredients – can be expensive, leading some critics to argue that much of the latest food craze is really one of a relatively few elites.

And even if people are buying beautiful in-season produce because they feel it lessens their carbon footprint or supports local jobs, that doesn't always mean they know what to do with their weekly allotment of Swiss chard and fingerling potatoes from the community farm.

"We get excited about what looks beautiful, like purple carrots, and that's fascinating," says Deborah Madison, a chef and cookbook author in Santa Fe, N.M. "But you need to understand vegetable families and why things reside in them."

The preoccupation of many with watching cooking shows on TV raises its own set of questions. Many critics level the same charges against them that they do against television in general: They make us passive – observers of, rather than participants in, life, in this case actually cooking.

"Most people don't want to spend the time cooking," says Mark Kurlansky, bestselling author of "Cod," "Salt," and "The Food of Younger Land." "They are buying frozen gourmet from Trader Joe's, or ordering in, or going out to eat, or buying from places that make premade meals."

Nor does the speed at which things happen on cooking shows – in half-hour segments, with an emphasis on competition – really reflect what actually happens in a kitchen, particularly among professionals. "TV has had a positive and negative effect on the culinary world," says Waysok. "The positive is that everyone wants to be the next Gordon Ramsay, and the negative side is that people think being a chef means yelling a lot and throwing things around the kitchen."

Still, a growing number of Americans today are becoming more sophisticated cooks and consumers of food. They are more skilled in their own kitchens, and, when they go out, they are dining in restaurants with a new generation of adventurous chefs. Is America the new Italy? No. But neither is it the era of Hamburger Helper.

Now all we have to do is make sure we don't obsess about it too much. As Trese Ainsworth put it when the family gave Peter the cooking class for a 40th birthday gift: "We signed him up for a karate class, just to keep things in balance."

• Gloria Goodale in Los Angeles contributed to this report.