Abortion opponents have a new voice

| Washington

With an easy laugh and ample charm, Charmaine Yoest doesn't at all appear to be Public Enemy No. 1 for the pro-abortion rights community. But the foundation of her rising influence – the accessibility of her approach – becomes clear when she settles in for an unexpectedly frank conversation about the stunning 2011 antiabortion legislative juggernaut that she has helped orchestrate.

This mother of five – who is not a physician, attorney, or lawmaker – has set the stage for sweeping antiabortion victories at the state level on the strength of her seeming candor, warmth, and camera-ready smile.

And so, she engages on the question of what animates her interest in advocacy like any smart girlfriend might. She says it was a miscarriage – which came early in her first pregnancy – that rocked her world. The intensity of her sadness caught her by surprise. It rained as she and her husband drove home from her physician's office, and Ms. Yoest says she felt that heaven wept with her. The experience made her wonder anew how anyone would opt to terminate a pregnancy voluntarily. And it stoked her already fervent belief that a society that presents abortion as an option is putting women in harm's way.

"We were so excited because it was my first pregnancy," she says. "I told everybody instantly. And within a few days I miscarried. And it was so awful, the whole physical process of going through that."

Yoest, the president and chief executive officer of Americans United for Life, a group that offers 39 pieces of model legislation for state lawmakers and advocates, is one of the key actors pushing a wave of highly restrictive – the other side would say dangerous and illegal – initiatives limiting access to abortion. AUL's goal is to eat away at the underpinnings of the protections provided by Roe v. Wade – the landmark United States Supreme Court decision that extended the right to privacy to a woman's decision to have an abortion – not necessarily to challenge it outright. At least not yet.

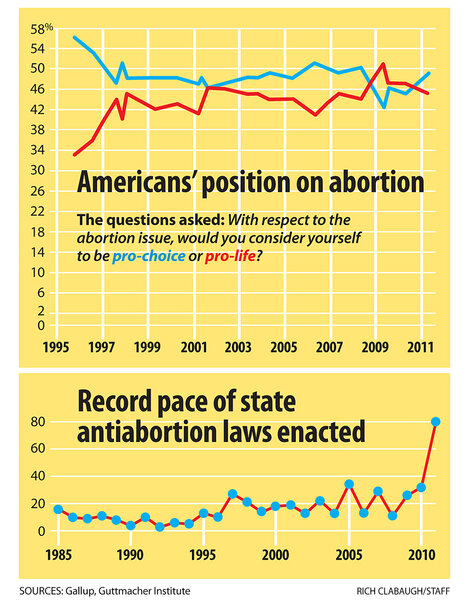

So far this year, AUL and other like-minded groups have caught their adversaries flat-footed; some 22 states have enacted a record 86 new measures in 2011, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which studies sexual and reproductive health and supports abortion rights.

Just two years after the election of a pro-abortion rights Democratic president, it appears the antiabortion movement has been reborn.

"We were expecting a bad year – we weren't expecting this bad of a year," says Elizabeth Nash, a Guttmacher public policy associate.

Yoest boasts that 22 of the 86 measures began in some form with AUL guidance. Taken in full, the reforms are sweeping and go much further than bills debated in recent years – like parental notification or consent – around which there might have been some, albeit limited, cross-party agreement, say abortion-rights advocates.

For example, some of the AUL-influenced results this year include:

•A Texas mandate that women seeking abortion undergo a sonogram, hear a description of the fetus from the provider, and wait 24 hours after this exchange before having the procedure.

•Kansas clinic regulations that essentially shutter abortion providers with stringent rules ranging from the temperatures of procedure rooms to the drugs and equipment that must be on hand. A federal judge temporarily blocked this law last month.

•Legislation in several states – including Idaho, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Virginia – permitting the exclusion from state health insurance exchanges of companies that allow coverage of abortions.

This flurry of activity comes in large part as a result of GOP victories in 2010 that provided Republicans with control of 21 statehouses and governorships, compared with 11 for Democrats, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Playing against type

But beside the undeniable political advantage, there's something else afoot, something Yoest embodies. She represents the changing face of the antiabortion movement. No longer are ideologically driven men necessarily the dominant spokesmen.

Despite her career in Republican politics, notable most recently for a stint as communications director on Mike Huckabee's 2008 presidential campaign, it's harder to peg Yoest in the traditionally one-dimensional caricature of an antiabortion advocate. She is not shrill, rigid, or somehow provincial in values or experience. She is not a fire-and-brimstone finger wagger, though faith is a centerpiece of her life.

In fact, Yoest has many of the attributes of a feminist – her career is a point of obvious pride and focus, and it has at times also dictated family moves and priorities – though she would strongly insist she has none of the sentiments. She holds a doctorate of philosophy in government from the University of Virginia, a degree she achieved after 10 years of study while raising her children. She is the daughter of two PhDs – a Fulbright-awarded economist father and a mother who specializes in communication theory. She is a breast cancer survivor, a marathoner, and the mother of an athlete on the Junior National World Development Rowing team.

While common ground is elusive in the fight over reproductive freedoms, Yoest's measured manner is a marked break with those of some of her peers and many fighting in the trenches.

Yoest's deliberative nature is home grown, a product of a peripatetic childhood experience that required adapting to new locations and schools and attracting new friends. So perhaps it is not surprising that she is the kinder, gentler face of a movement winning not just the legal war but the spin game at the moment.

"It's not too difficult to imagine that somewhere in some major pro-abortion organization, there's a bull's-eye with Charmaine's face in the middle," says Gary Bauer, Yoest's former boss at the Family Research Council.

A popular thinker

Yoest was first challenged to dig deep foundations for her antiabortion sensibility at Oxford University in England, where she went to study under conservative ethicist David Cook after serving under Mr. Bauer in the Reagan White House as an intern and staffer.

"I want to be a part of the intellectual discussion defending family issues and life," Yoest says she told Dr. Cook. "He was wholly unimpressed. He said, 'Go write me a paper on why abortion should be legal.' Apparently, I didn't do a great job at it. He really helped me focus on where I didn't understand my whole argument. It changed the whole way I think about the issue. He really challenged me – defend it, defend it, defend it."

Yoest says she learned that her adversaries' arguments shift ground and divert attention from what she believes is the essential fact: Abortion takes a human life.

If there was any sign of Yoest's future calling, it was that she was always "a little adult" – eager for dinner-table discussion of the topics she read about in Newsweek, recalls her mother, Janice Shaw Crouse.

Though Yoest was born in Lexington, Ky., the family, which included a younger brother, moved frequently for the Crouses' doctoral work and teaching assignments. They bounced from Indiana to upstate New York, and then overseas when Mr. Crouse won a Fulbright Fellowship to teach at National Taiwan University in Taipei.

The two years abroad were formative for Yoest and her brother, who were elementary-age students old enough to appreciate the journey, which included swim meets in Okinawa, Japan, and a summer traveling with their parents around Europe.

Yoest was both brainy and social: a National Merit Scholar finalist and a high school cheerleader.

"She was never one to follow the crowd, but she still was very popular," Ms. Crouse recalls. "She's a very genuine person. What you see is what you get."

The family went to church every Sunday and regularly read the Bible together. They never ate a meal without praying first and never made major life decisions without reflecting on them, says Ms. Crouse, whose parents were Methodist ministers.

"Charmaine comes from a family that is willing to work," Ms. Crouse says. "We understand the value of work. God expects everybody, including women, to live up to their potential."

A traditional working mom

It was through the Fourth Presbyterian Church in Bethesda, Md., that Ms. Yoest met and, following her time at Oxford, married fellow parishioner Jack Yoest, a dozen years her senior. For a time, the Yoests lived in Richmond, Va., where he served briefly as a senior assistant to the secretary of Health and Human Resources in the administration of Gov. Jim Gilmore, a Republican.

Ms. Yoest was raising her children and commuting to Charlottesville, Va. to work on her doctorate, which examined parental leave policies in academia. They later moved closer to campus so she could complete her degree.

"She was a very good student. She was an 'A' student," says Steven Rhoads, Yoest's dissertation adviser at the University of Virginia. "I'm not surprised she took a more activist route. I think that was important to her.... She is one of a number of women who are going to make a mark for themselves beyond the family, yet are not going to want to turn their kids over to day care."

The couple, married for more than two decades, now lives in a Virginia suburb of Washington with what Mr. Yoest, a management consultant, calls their "Penta posse": Hannah, 18; John, 16; Helena, 14; Sarah, 10; and James, 7.

The children are a close-knit pack of brunettes. With busy working parents, each helps to keep the family ship on course. Helena, an early riser, makes everyone's lunches – peanut butter-and-jelly or ham-and-cheese sandwiches – in the morning. Sarah unloads the dishwasher. John mows the lawn. And Hannah, who this fall starts at UVA on a rowing scholarship, drives her siblings to school. Many days, family members stay in touch via Facebook.

Routinely, Ms. Yoest admits with just mild hesitation, the family misses Sunday church services because one of the kids has a sporting event.

The Yoests bonded over politics during the 2008 campaign when Ms. Yoest worked for Mr. Huckabee. After painting the family Chevy Suburban and dubbing it the "Hucka truck," they spent six weeks on the road, traveling through New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Iowa, where the kids say they discovered phone banking – and that it's a rare voter who hangs up on a child calling for campaign support.

After Huckabee flamed out, Yoest negotiated a job with AUL allowing her to take one child with her on each business trip – an effort to expose them to different parts of the country and provide her with additional quality mom time.

When Yoest told her parents of the opportunity at AUL, they asked her to consider seriously if she wanted to be a one-issue advocate, to give up all the other matters of political and public interest to her.

Ms. Crouse says the family was never issue-focused when Ms. Yoest was a child, and that abortion was not a topic of conversation in the house. Faith was viewed first and foremost as the critical foundation for living "authentic lives" and treating friends and strangers alike with kindness. Ms. Yoest says she has never had an abortion and that she would never consider it. But when it comes to prevention of unwanted pregnancy it's worth noting that she is less forthcoming. Contraception is not part of the AUL platform. And abortion foes often disengage on this question – because the use of birth control suggests sexual activity that is not purely procreative. For her part, Yoest bristles when asked about her personal use of it. She says she believes there should exist some "zones of personal privacy."

Yoest does note that the stresses she and her husband endured during her fourth pregnancy added nuance to her thinking about the politics – and humanity – of the abortion issue; he was out of a job, finances were tight, and they had to sell their home.

"You could search and search and search and never find me minimizing the choice that some women make, because I do completely understand the panic, the fear of how are you ever going to be able to handle the situation," she says.

But what about rape? Or when a mother's life is at risk as a result of the pregnancy?

In the case of the former, Ms. Yoest says that she is sorry for the pain of the mother. But heaping tragedy on tragedy is no solution. Abortion, she says, "only adds more irrevocable sorrow."

And in the latter circumstance: "If a woman is facing a pregnancy that threatens her life, I would make sure she knew a real pro-life doctor who would treat her and her baby as two patients," she says. "If a baby dies in the process of trying to save a mother's life, as long as the intention is to save both lives, then there is no moral system in the world that sees that as equal to elective abortion."

Yoest says she believes, and she points to data her adversaries would readily dismiss, that the majority of women who have abortions regret their decisions and that there exists a heightened risk of drug and alcohol dependence, suicide and psychiatric admissions for women who have had an abortion, and increased risk of premature birth for later pregnancies.

"Every single human being has crisis points in their lives, you have to come to grips with that," she says. "You have to figure out how to put your life back together and move forward. The thing that's exciting to me about pregnancy is that even in the most awful circumstances, there's a redemptive opportunity and a hope that comes from new life."

Hope in crisis is not a situation with which Yoest is unfamiliar. After a breast cancer diagnosis in early 2009, she underwent a mastectomy and months of chemotherapy.

Her husband and sons shaved their heads in solidarity. "That day I remember," she says. "I will always remember."

Massive menu of model legislation

Yoest calls AUL the legal wing of the modern antiabortion movement. The group is fed by individual and foundation donations and has an annual budget in the modest ballpark of $4 million. Its bread-and-butter resource, in addition to its staff of seven attorneys and two paralegals, is its annual report – Defending Life: Proven Strategies for a Pro-Life America – which gives local law-makers resources for building their own bills. The telephone book-sized guide outlines which states are the friendliest, and not, for antiabortion legislation and ranks them on their laws governing legal recognition of the unborn and newly born, end of life matters, and bioethics, among other issues.

"I think AUL has become the premier pro-life organization in the country," says Huckabee. "I think their approach has been far more objective, a great deal more thoughtful. They're working not toward just raising an issue, but also toward changing minds and hearts, engaging people in honest, thoughtful discussion as to why every life matters."

And that's what pro-abortion rights advocates worry about. It's easier to address an extremist adversary, not so one who talks with some sensibility about her underlying belief system. And perhaps it's why, time and again, when asked for direct reflection on AUL or Yoest, her foes prefer to deflect to a discussion of the ways her group's legislation fits into a larger effort to restrict the reproductive health freedoms of the nation's women.

Yoest's backers, of course, do not refrain from praise. Ellen Kolb, the legislative affairs director for New Hampshire's Cornerstone Action, a conservative public policy group involved in passage of that state's parental notification law, says the Republican sponsors of the state's bill went to AUL for guidance about what has worked across the nation. Ultimately, Granite State lawmakers in June overrode the veto of Democratic Gov. John Lynch.

"I know of no other organization that is a better clearinghouse for current legal information on life issues," Ms. Kolb says.

When a pro-abortion rights president is in the White House, the push at the state level is always more intense, observes Jordan Goldberg, state advocacy counsel for the Center for Reproductive Rights in New York. But she says she is "deeply troubled and of course angered by the agenda" AUL and others are pursuing.

"I don't know that I would be too proud of it if I were them," she says of AUL's collection of model bills. Ms. Goldberg says legislation passed so far this year – including AUL-backed clinic regulations so restrictive that in Kansas, for example, all three abortion providers would have had to close their doors – make it impossible for women to access the range of health-care services they need.

In Texas, the AUL-backed sonogram measure is under review of a federal judge. A Center of Reproductive Rights lawsuit asserted that the law hijacks the doctor-patient relationship and "imposes stress and emotional strain on women as they prepare to undergo a medical procedure."

"Basically these laws say to women, 'We don't trust you or think you know how to make a decision,' " Goldberg says. "These kinds of regulations, in addition to being clearly and overtly sexist, they are also somewhat insidious because they regulate the practice of medicine that is not based on standards of care."

There is a divide in the antiabortion movement, meanwhile, about this approach. Some believe officials should strive to overturn Roe v. Wade – and that anything less is missing the point. Others, including Yoest, suggest that in the short term they can do much to reduce the number of abortions performed by pushing these types of initiatives and cuts to funding of Planned Parenthood, among other proposals. Avoiding a Supreme Court fight – where a decision about abortion would probably fall to Justice Anthony Kennedy, who signaled in a 2007 ruling that he has hesitation about later-term procedures but whose commitment is not yet clear – has strategic benefits.

AUL has avoided involvement in some of the bills that, if challenged, could get batted down by the nation's highest court. Among them, a South Dakota measure requiring women to wait 72 hours for an abortion. The initiative also requires a visit to a crisis pregnancy center where a woman would be advised of her alternatives. A judge has imposed a temporary injunction.

Yoest says this of her group's incrementalist strategy: "You don't have to overturn Roe to actually make progress at the state level." One option is to let Roe "crumble under its own weight and become irrelevant," she says.

Dictating the national conversation

The nation is decidedly split when it comes to abortion. According to a Pew Research Center for the People & the Press survey conducted in February, 54 percent of Americans believe abortion should be legal in most or all cases, while 42 percent said it should be illegal. Gallup polling has fluctuated in recent years, though the divide between Americans who self-identify as "pro-choice" versus "pro-life" has narrowed considerably since the mid-1990s when there was more than a 20 percentage-point edge among those favoring reproductive freedoms. In a 2009 Gallup poll, 51 percent of respondents said they were "pro-life" while 42 percent were "pro-choice." But Gallup's 2011 numbers indicate that 49 percent call themselves "pro-choice" compared with 45 percent who are "pro-life."

The antiabortion movement is having success in dictating the national conversation about abortion, says Kathryn Kolbert, the civil rights attorney who successfully argued the landmark 1992 case Planned Parenthood v. Casey before the Supreme Court. Ms. Kolbert views the initiatives being pushed by AUL and others as "totally draconian," including, she says, a relentless push to defund Planned Parenthood, an effort AUL renewed in July with gusto. With half a dozen GOP members of Congress by her side, Yoest issued a report – titled The Case for Investigating Planned Parenthood – suggesting that lawmakers worried about the debt ceiling and America's fiscal crisis shouldn't be providing public tax dollars to an abortion provider.

While Yoest took a calm tack during the press conference, asserting that the report allows the American people to look at the issue "openly and honestly" and decide for themselves, others were more direct.

"This provides a blueprint to investigate a group that has literally gotten away with murder," says Rep. Chris Smith (R) of New Jersey.

Democratic pollster Celinda Lake says antiabortion congressional Republicans are overstepping. They gained power at the state and federal level last year on a message of job creation and fostering a healthy economy, not on a radical social agenda. Ms. Lake says tea party candidates, in particular, won the hearts of voters because of their small-government libertarian bent, but, she adds, they were selling a bill of goods. And with the economy still lagging, the focus on antiabortion legislative activity could come back to haunt conservatives in the 2012 contests – especially with young single women being a key swing voting bloc.

"There's a lot of buyer's remorse going on out there," Lake says. "Voters didn't vote for this. When it comes to the abortion issue in particular, we've had 30 years of fighting about this issue, and enough is enough. Voters are really tired of it."

It's harder to forecast if the issue will become a matter of major debate in the 2012 presidential contest. The economy and jobs are still voters' overwhelming first concern, polls indicate. Yoest says AUL isn't interested in advocating for a candidate. Any of the GOP hopefuls are better on the abortion issue than President Obama, she says during an interview in her office, where photos of her family at the March for Life in Washington adorn her bookshelves.

Moral bearings

In AUL's front waiting room, meanwhile, visitors won't find drawings of babies in different stages of development or graphic leaflets. They can browse The Washington Post or The Wall Street Journal. Or watch the television, which is turned to Fox News. Or perhaps take in the irrefutable wisdom – scripted, at Yoest's direction, in large lettering on one wall – of one of the nation's great Founding Fathers, Thomas Jefferson:

"The care of human life and happiness, and not their destruction, is the first and only legitimate object of good government."

Yoest frames her argument similarly. "You either believe it's a life or you don't," she says. "The intellectual underpinnings really do matter. And they matter for our culture. If you can't draw the lines, you lose your bearings. You lose true north if you can't defend innocent human life."