9/11 racial profiling: Where civil rights met national security

Loading...

| Winnipeg, Manitoba

When the flutter of fingers over maroon prayer beads fails to expel intrusive memories, Cameran Sadeq seeks the high ground – literally. He heads for "Garbage Hill," a landfill that is one of the highest points of elevation in this prairie town.

"I feel good there," Mr. Sadeq explains about how an uncluttered horizon makes him feel free, and can even put him in mind of "my back home" in Kurdish Iraq. "My problem is the pressure of [being stuck] in one place too long and [the feeling that I] speak but no one is listening."

Feeling entrapped and unheard plagues this refugee in traffic jams, waiting rooms, and even in the concrete-block walls of his apartment as his five dark-eyed children play jungle gym on his legs.

One of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi Kurds who fled Saddam Hussein's genocidal attacks in the 1980s and '90s (think "Chemical Ali"), Sadeq spent his early adulthood trying to find a safe home but being shunted into tight physical and mental spaces. While living at a refugee camp in Syria, he played dangerous hide-and-seek with Syrian police who beat him before he escaped to Lebanon; from a Lebanese refugee camp he was smuggled aboard a cramped and rickety boat across the Mediterranean to Cyprus; and languishing in a Cyprus prison for his illegal entry, he climbed a tree and refused to come down until United Nations officials came to hear his claims of refugee status – claims that, once heard, won him refuge in the United States.

But the fear of being entrapped and ignored seethes in him most when he talks of the 9/11 attacks and how the US recast him from welcome refugee to enemy; how a simple wrong turn on a Miami street caused authorities to detain him for months because – as a Middle Eastern Muslim man – he somehow resembled Al Qaeda's hijackers.

The 10th anniversary of 9/11, for Sadeq, is a reminder of a double betrayal: by fellow Muslims who attacked his new homeland and by Americans who turned the attack on the US into an attack on him.

The decade since has brought Sadeq what he always wanted: a big, rollicking family and a safer homeland. Indeed, stretching his linebacker-arms wide, he says his new Canadian citizenship is like having a "big mother" to protect him – a "huge gift" that has given him a passport that allows return visits to Iraq, welfare payments while he finds a new career after a construction accident injured his back, and a future for his children.

But the decade has not healed the insult of detention – and the way it effectively ended his American life by making him penniless and a sort of pariah in the Iraqi community in Detroit, where he used to live.

And America's effect on him echoes complaints often heard in the Muslim world: a sense of distrust, misunderstanding, and as Sadeq repeats, "no one listening."

Sadeq was a casualty of one of the US's most challenging ethical moments: the crackdown on civil liberties in the national security panic following the 9/11 attacks. An untold number of American residents like Sadeq – citizens and aliens – were swept into detention based on racial profiling. Within two months of 9/11, according to a 2003 review by the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Justice, authorities "stopped reporting the cumulative totals after the number reached approximately 1,200, because the statistics became confusing."

"Middle Eastern detainees we spoke with felt as if they'd been thrown into a black hole they might never be able to crawl out of," recalls Cheryl Little, an attorney whose Florida Immigrant Advocacy Center represented many detainees.

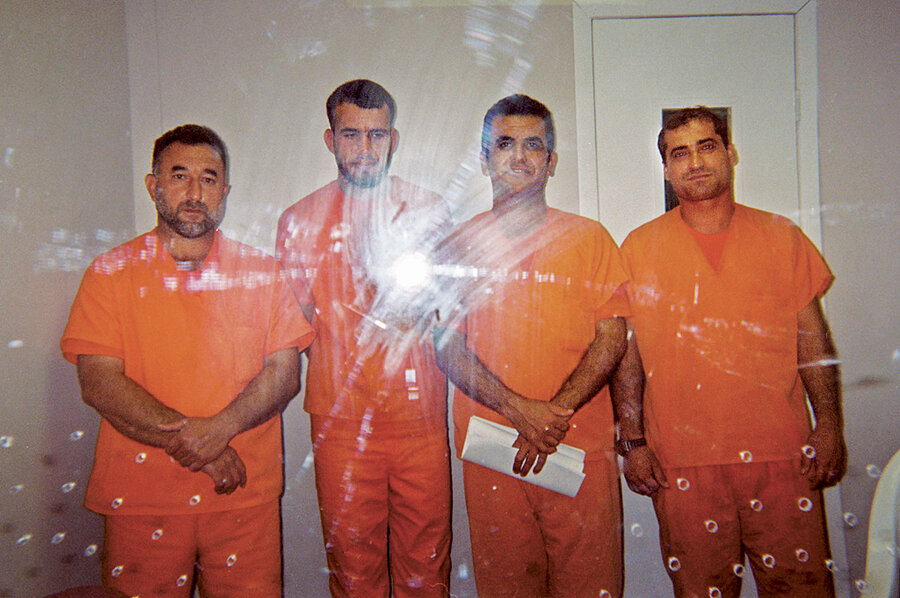

Sadeq spent nearly five months at Miami's Krome Detention Center after he and three Iraqi companions unwittingly made a wrong turn into a restricted area at the Port of Miami. They were going to visit a cruise ship worker they knew.

Somehow, in the climate of fear after 9/11, Sadeq's social radar, hampered by beginner's English, did not pick up on the ominous signals: The terrorists were Middle Eastern, and – as he puts it now – Americans "didn't like my face."

Sadeq's attorney at the time, Michael Vastine, says the pretext for his detention was a minor paperwork technicality. After one year in the US as a refugee, Sadeq was required to adjust his visa status, and he had not yet done that. It is a violation not normally prosecuted. (Indeed, the Obama administration last month announced it would allow about 300,000 illegal immigrants facing deportation based on such technicalities to stay in the US.)

But plainclothes FBI and Immigration and Naturalization Service officers used the opportunity to grill Sadeq: "Are you a terrorist?" "Do you know any terrorists?"

Sadeq explained what might be considered his pro-American credentials: In 1991, at age 17, he carried a Kalashnikov in a US-sponsored Kurdish rebellion against Mr. Hussein; his older brothers were tortured for their resistance work; and Kurds are not Arab. It offended him that they seemed not to understand.

Sadeq's sense of principle and religious grounding – "Allah knows I'm not the one they were looking for" – was memorable and a little alarming to Mr. Vastine. Compared with some other detainees who took "the path of least resistance," says Vastine, Sadeq "kept insisting, 'Give me a lie detector test,' and ... had his wife call Al Jazeera."

They didn't listen, Sadeq says now with quiet intensity.

Eventually Sadeq was released and returned to Detroit to find he'd lost his apartment and all its contents, his car, and the savings he'd deposited for a truck-driving course. He asked for but received no compensation from the US, and few in the Iraqi community would help him because of fear that he would bring the attention of law enforcement on them, too.

So, with just $12, he fled to this small Manitoba city 60 miles above the US border, vowing he'd never go back. He joined Samira Moustafa, whom he'd met years before in the Syrian refugee camp and had married just before his arrest.

Here, where most of his immigrant friends and neighbors have their own stories of war, flight, and trauma, Sadeq's trials are like one more volume on the library shelf, rarely cracked. And Sadeq smiles when describing being absorbed into the local community without questions about his past, noting that he is a proud beneficiary of the provincial license plate motto: "Friendly Manitoba."

Ms. Moustafa is like her husband's Greek chorus nodding vigorously, frowning, rolling her eyes, or poking him with a teasing elbow throughout interviews. "We are one," he says when inviting a reporter to come to their home without even consulting her. The handsome couple's light-hearted rapport – and the comic industry of their five children, ages 9 months to 7 years – approximates the dream of family that Sadeq, now 40, always had.

Though unemployed for two years with a severe back injury he suffered as a construction crane operator in Vancouver, Sadeq – with public assistance and no small help from Moustafa's extended family here – struggles to provide what the family needs. They wheel around in a minivan, live tightly but comfortably in a two-bedroom apartment where the big-screen TV is constantly on Al Jazeera or Al Arabya, send the two school-age children to an Islamic elementary school, and drink liberal amounts of sweet tea. Sadeq has kicked a chain-smoking habit and has been accepted to a University of Manitoba program that will teach him to read and write English so he can later enter mechanic training. But at the heart of his existence, he says, is the constant tension between "my back home" in Iraq and his new roots in Canada.

"What's breaking me," he says, is that the kids will never "share the same 'back home' " with him. "I don't want to be a dictator and trade my kids' future for my [own] happiness," he says, noting that he's already instilling the expectation that they all attend college, which he thinks would be impossible in Iraq.

The signs of the West's pull on the family's mentality are noticeable. There's the mixed language patter in his home – the kids speaking to the parents in English with such colloquialisms as "brain freeze!" and the parents speaking exclusively in Kurdish. There's the evolution of Moustafa: a decade ago she was quiet and submissive and dressed very modestly (though not as modestly as her mother who covers herself from head to toe); now, at a recent family picnic at Assiniboine Park here, there were jeans and a hint of cleavage above her leopard-print shirt and no reserve in her conversation. She rolled her eyes jokingly when Sadeq refused to have a family portrait taken for publication, because "they did nothing" to deserve the kind of publicity his detention might bring them (though he deemed a photo of baby Ibrahim harmless, because the boy won't look the same in a few months).

Yet still, Sadeq has barely engaged in Canadian affairs. He voted once, but admits his focus is more on Iraqi and Kurdish politics. He daily logs on to the websites of each Kurdish political party. It was his first trip home in 2007 – to see his ailing mother, whom he'd lost track of as the family fled to various countries in 1991 – that rekindled the idea that he could possibly live there again.

While the news of Osama bin Laden's killing by US forces last spring was a symbolic moment in the decade-long resolution of 9/11, it offered little healing for Sadeq. His worldview from Winnipeg, influenced heavily by Arab satellite channels and, he adds, "Democracy Now!" anchor Amy Goodman, is that the US continues to make the same mistakes, from the way it deals with average Joes like him to its conduct in global affairs.

"Osama bin Laden was a huge troublemaker for more than the US," he says, noting that he's glad Mr. bin Laden was caught, but thinks his killing foreclosed answers to many mysteries. "But nobody says this guy is [one] Muslim; they [equate him with] Islam. That's a problem for me."

Sadeq, a Sunni, says he's not "a tight Muslim," but he does use an iPhone alarm for the prayer hours and believes Allah is watching over him. And his religion – closely held or not – is a sore point in his memory of detention. He has a way of bitterly spitting out English acronyms to make his point: "Generals, CNN, CIA, FBI: They're like messengers who mix Islam with the [individual] Muslim."

"I'm not saying I hate the US," he says calmly, "It has a right to catch whoever it wants to ask if there's some connection to terrorism...."

And then, hoping to be heard, he leans forward: "[But] treat people the way you want to be treated."

[ Video is no longer available. ]