Wyoming sheriff bans cowboy hats and boots: Insensitive or good policing?

| ATLANTA

There’s a new lawman in town, at least in Sublette County, Wyo., and Sheriff Stephen Haskell says no more cowboy boots nor 10-gallon hats on the job. Miffed, a veteran deputy, Gene Bryson, retires on the spot, saying some things – especially a man’s hat and boots – shouldn’t be up for debate.

It’s in part a story of police progress on the American frontier, where rustlers, hustlers, wranglers, and (now) meth tweakers still ramble around under the vast open skies.

But while the boots ban may be an honest effort by a new sheriff to professionalize a rural police department that patrols 5,000 square miles and serves 10,000 people, the 40-year veteran deputy might have a point, too: What better way to humanize the local constabulary than by letting them look like the folks they police?

Though it’s in part a light-hearted anecdote from a sparsely populated part of the West, the hat-and-boot showdown does in some ways resonate beyond the Wyoming ranges, particularly at a time when police organizations ponder reforms to bridge at times wide divides between deputized and non-deputized citizens.

Studies have shown that citizens do come away with different impressions of police depending on what styles of clothing and and even manner hat they wear.

For some experts, Sheriff Haskell’s rule-change reflects a growing awareness that police professionalization requires uniformity.

“Just as a matter of safety and effectiveness, it’s absolutely the right thing to do,” says Samuel Walker, the author of “The New World of Police Accountability,” and an emeritus professor at the University of Nebraska in Omaha. “The resistance is a classic example of how there’s a culture among the deputies that’s clinging to an old-fashioned approach that is just no longer justified.”

Sheriff Haskell, a former Marine, is from the professional school, where the notion of officers customizing their uniform until they look like a “Skittles platoon” is, at best, confusing and, at worst, dangerous. He cites deputies slipping on ice in their cowboy boots or chasing down wind-blown cowboy hats, as examples.

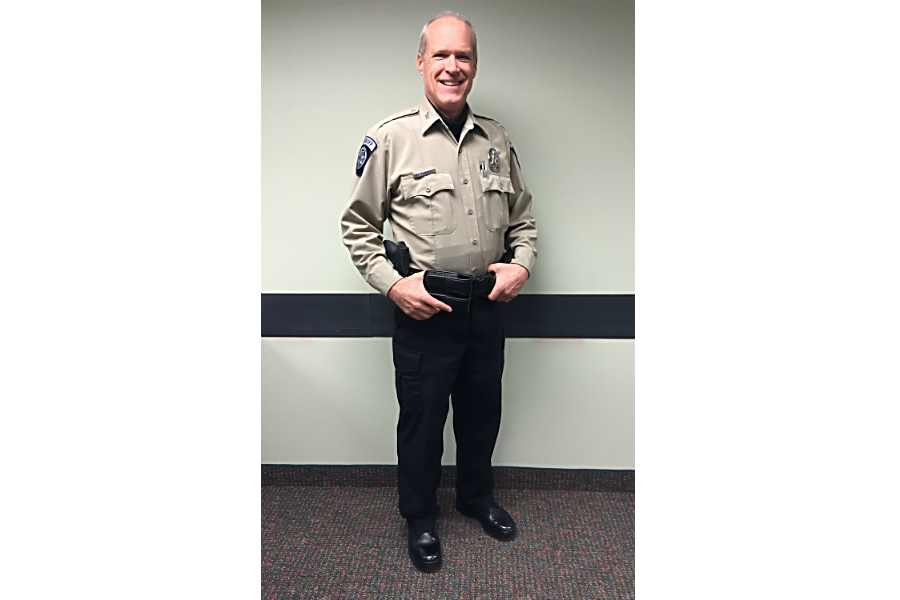

The new uniform includes black trousers, a tan shirt, black boots, and a black baseball hat. “We are one team unified in one purpose – that is to do our job,” Haskell told the Casper Star-Tribune.

Most of the county haven’t had a problem with Haskell’s decision, says Pinedale, Wyo., Mayor Bob Jones. Deputies in Sublette deal with everything “from minor vandalism to capital crimes,” says Mr. Jones.

“I think it’s been positive,” he adds. “He’s a new sheriff and he’s trying to make things uniform. He has 25 years in the Marine Corps, so I think he’s trying to instill some of his values [regarding] working together as a team, and everyone having the same uniform is integral to that, even though it might seem insignificant.”

Mr. Bryson, who retired shortly after Haskell announced the uniform policy, says he wears his cowboy regalia, which is a common outfit in the town of ranchers and natural gas wildcatters, as an expression of his geography, a nostalgic, practical, and comfortable look of the Western experience.

“I’ve had a cowboy hat on since 19-I-don’t-know,” Bryson told a local newspaper. “I’ve always worn a cowboy hat, all my life.”

For many lawmen in the West, the classic wool vest, white cowboy hat, and sturdy cowboy boots are more than a fashion statement. It embodies the values of the West, including its unique policing tradition.

The Western dress by deputies is “what’s accepted within the community and the state, and it’s a tradition of many sheriffs’ offices to hold onto our traditional Western values and that heritage,” says Jim Pond, the former sheriff of Albany County, Wyo., who is now executive director of the Western States Sheriffs’ Association, in Laramie, Wyo.

Mr. Pond says “it’s obviously within [Haskell’s] purview to demand a certain appearance.” But the safety concerns, he adds, might be overblown, adding that there are plenty of cowboy boots on the market with high-grip Vibram soles.

Studies have also shed some doubt on whether a baseball cap commands more respect than a cowboy hat.

One study cited by Richard Johnston in a PoliceOne report looked into what kind of responses different hats elicited, and how the various headgear reflected on the officer’s authority.

The study found that a “Smoky Bear” style hat, which is reminiscent of a cowboy hat, conveyed more authority than a baseball cap.

However, an experiment in Menlo Park, Calif., in the 1970s suggested that civilian-style uniforms may also elicit a less-than-desirable response from the populace. The Menlo Park police returned to a paramilitary uniform after eight years of wearing blazers, white shirt, and ties, and saw assaults against police officers immediately decline after rising for several years with the more-casual uniforms.

But it's what the uniform does for the man or woman wearing it that may have the greatest impact on policing in general, one psychologist says.

“Wearing more tactical versus civilian gear probably has the most effect on the officers themselves, where a paramilitary uniform gives them a sense maybe of invulnerability that they wouldn’t have in short sleeves,” says Leonard Bickman, a psychology professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, who has studied the impact of police uniforms on the public. “That might be more important than the effect it has on the crowds around them.”