Supreme Court allows controversial lethal injection drug

The US Supreme Court upheld the use of a drug linked to botched executions Monday, saying it did not violate a constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

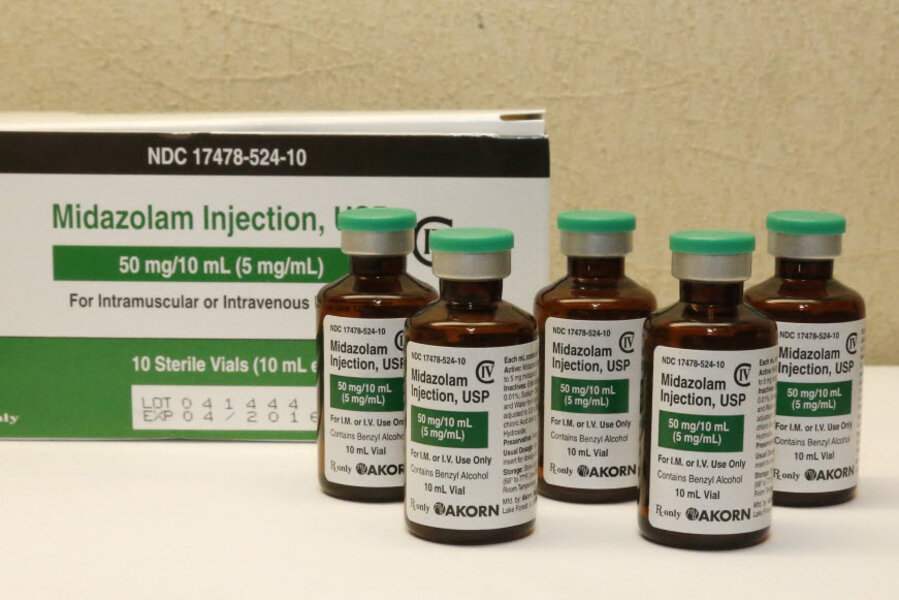

Justices ruled 5-4 in the case Glossip v. Gross, defending a lower court decision against four Oklahoma prisoners on death row who wished to prohibit the use of the drug midazolam, which was used in executions in Oklahoma, Arizona, and Ohio to unanticipated effect.

Midazolam is designed to put a person to sleep before administration of a lethal injection, but in three cases last year inmates awoke and appeared to suffer violently before dying, suggesting that the sedative did not work as intended.

As Warren Richey of the Christian Science Monitor wrote,

The case is significant because it arises at a time when states are finding it increasingly difficult to purchase drugs for lethal injections in the face of widespread refusal by various companies to sell drugs for capital punishment.

The boycott means that as drugs considered effective for lethal injections are no longer available, states are turning to drugs that are somewhat less effective. The question is, are they effective enough?

A high court decision in the Oklahoma case may offer essential guidance to states struggling to continue to carry out executions without violating safeguards of the Eighth Amendment.

The sedatives sodium thiopental and pentobarbital were traditionally used until recently, and their effectiveness was undisputed among medical experts. However, faced with pressure from anti-death penalty activists, drug manufacturers began refusing to sell states these drugs as well as similar ones for use in capital punishment, causing Oklahoma to switch to midazolam.

An investigation into one of the cases pinned the mishap on the technician’s failure to properly insert the needle, not on the drug itself.

Justice Samuel Alito wrote in the majority opinion, “Testimony from both sides supports the District Court’s conclusion that midazolam can render a person insensate to pain.”

In the dissenting opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor argued that the court was “misconstruing and ignoring the record evidence regarding the constitutional insufficiency of midazolam as a sedative in a three-drug lethal injection cocktail, and by imposing a wholly unprecedented obligation on the condemned inmate to identify an available means for his or her own execution.”

This report includes material from the Associated Press.