Global sports trade: athletes hurdle national borders for a better life

Loading...

| Madrid and Lleida, Spain

Mohamed Marhum became the man of the house early in life. Just 7 years old, he helped support his single mother and four younger siblings by working for tips carrying everything from bags of cement mix to bushels of food across the border between Morocco and the Spanish enclave Ceuta on the northernmost tip of the Strait of Gibraltar.

On a day when his job went long and he found himself on the Spanish side of the border when it closed for the night, he did what he was best at. He ran. But even though Mohamed was faster than most boys his age, he still couldn't make it through the next crossing. Police nabbed him. And because he didn't speak Spanish and didn't have ID, he was taken to a Spanish-run youth center where, he says today, he endured a steady regime of physical abuse. After three weeks, he ran again, escaping back to his family.

Thirteen years later, Mohamed Marhum is still running. But today's he's running for the same country he once so desperately tried to escape as one of Spain's leading long-distance racers and gold medal hopefuls for the London 2012 Olympics.

Think you know Europe? Take our geography quiz.

Long, lean, and muscular, Mr. Marhum is now 20 years old and spends most days at Spain's top training facility at the Complutense University of Madrid. While his rise from poverty in Morocco to sports glory in Spain is the stuff of legend, it's a story line that is increasingly common in the global sports trade as talented young immigrants from developing countries are finding easier access to the West by exchanging physical talent for naturalization.

While changing flags is as old as the Olympics itself, the global athlete trade is drawing more scrutiny today. Nobody is contesting that many cases represent legitimate immigration, but others amount to blatant "shopping" for talent, with governments granting nationality within days in exchange for cash and the promise of a better life, indeed an offer many can't refuse.

But globalization is making it harder to differentiate between an athlete who becomes an immigrant and an immigrant who becomes an athlete. And it's harder to tell if countries are acting on humanitarian grounds when granting visas to athletes or if they are getting an unfair competitive advantage to reach podiums and glory.

"Unfortunately it's not a good system, but it's difficult to improve," says Denis Oswald, a law professor and director of the International Centre for Sports Studies in Switzerland, and also a member of the International Olympic Committee. "I wouldn't say it's fair, but it's the way it is. You would need almost a court assessing each case individually because there are some very legitimate changes of nationality," Mr. Oswald says, "but even that would be almost impossible."

"It would be helpful to at least harmonize between sports, because we can't do anything as long as every country is sovereign to decide when to grant nationality," he says. "We considered the possibility of adding time of residence as a condition, but even that is also difficult to check because athletes travel so much and athletes have to train in different countries."

Every year since 1998, an average of 25 athletes have switched the country they run for, according to the Monaco-based International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF). That doesn't take into account immigrants who have never competed for a previous national team. The overall number is not tracked globally.

Marhum is one of those unaccounted for, because he never actually ran for the Moroccan national team.

Soon after he fled the youth center, life for him became harder outside the "jailhouse," as he called it, than inside. So he intentionally got himself recaptured by immigration police and was put back into the Ceuta youth center. He wasn't sure what that would lead to, but like millions of young Moroccans, he thought it could be his path to Europe.

He kept running and eventually began winning races. He was noticed in 2009 by a Spanish sports recruiter, who arranged for Marhum to complete school in Spain. Last month he placed first in the 10,000 meter youth division cross-country race during a national meet and also took first in the 4,000 meter general race.

His application for Spanish nationality, which for a typical Moroccan immigrant requires at least a decade of residing legally in Spain, has been promoted by the Spanish Athletics Federation. His trainer, Luis Miguel Landa, who is also Spain's athletics national team coach, is pressing for him to get his passport in time to qualify for the national team during the next meet in April.

"It's tricky," says Yann Hafner, a lawyer based in Nottingham, England, and a PhD candidate writing his thesis on sports and nationality. "Each athlete has their own story. We try to differentiate [between] athletes naturalized because of their sporting ability and immigrants that make it as athletes."

"We don't have uniform rules," Mr. Hafner continues, "which is a problem because some countries are able to naturalize faster. In Switzerland, it takes 12 years to get citizenship, but in France there is a special provision to naturalize when it's in the interest of the state – which is applied to athletes."

Middle Eastern countries are known for "buying" talent. Qatar and Bahrain have openly granted nationality to world-class athletes within days. France has naturalized 41 foreign athletes since 1998, all of whom had already competed for their native country; the US is next with 25, Spain with 21, and Canada with 11. Qatar comes in with 7 and Bahrain with 4, according to the IAAF.

But the difficulty of harmonizing rules is illustrated by the number of athletes "lost" by countries. The US has lost 22 athletes to other countries' national teams, while Russia lost 21, 18 left Kenya, 16 left Morocco, and 13 left Cuba. Spain hasn't lost any.

Moroccan-born athletes hold many of Spain's hopes for Olympic glory. Besides Marhum, there is also his friend Abdelaziz Merzougui. When he was 15 he paid a fixer 600 euros for a slot on a crowded raft that took 36 hours to cross the dangerous Atlantic waters separating Morocco from the Spanish archipelago of the Canary Islands. "I didn't know if I was going to make it," he says.

Merzougui won his first gold medal with Spain in the junior cross-country 2010 European championship race last December. He, too, is considered one of Spain's most promising athletes. As a minor, it took him less time to get his Spanish nationality – with the help of his trainer, who pulled some strings to get his file prioritized.

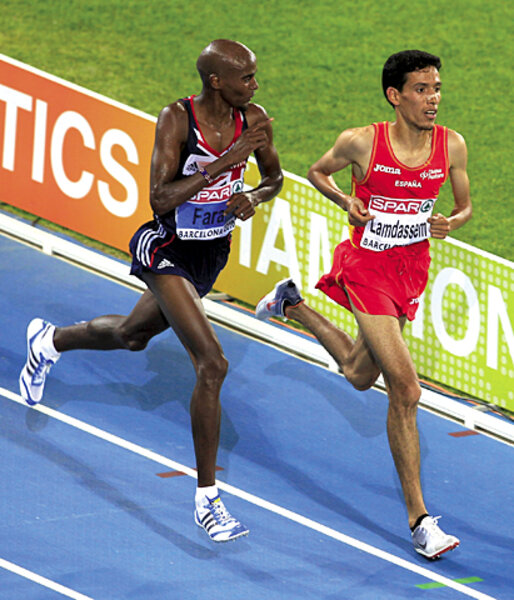

Merzougui left behind his family in the desert town of Guelmin in southern Morocco following the success story of his 29-year-old friend Ayad Lamdassem, who in December won the silver medal for Spain in the senior competition of the European Cross Country Championships in Portugal.

"When he arrived, he just called and said, 'Hi, I'm here,' " says Lamdassem in his humble apartment in Lleida, a small city south of Barcelona. "Abdelaziz once told me he would join me one day, but I had no idea he was getting on that raft. That's crazy. I wouldn't have allowed him to."

Lamdassem, originally from Sidi Ifni on the Moroccan coast, came to Spain in 2002 as part of a Moroccan university athletics team. Along with two other team members, he stayed behind, and now is married and has two children. Because he was a promising athlete, sports authorities pressed to get him his nationality in just five years.

"Half of the athletes I know from Morocco are trying to get into Spain, into Belgium, into France. It doesn't matter. It's not a question of if, but when," Lamdassem says. Most don't have the talent to make it in Europe, "but that doesn't matter because you can still get your papers and work in something else, and that is better than staying in Morocco."

He disputes the idea that Spain has bought talent. "It's not them, it's us. We came here. We have a chance to compete, to have a good life for our families, to study, and have jobs. In Morocco, even if you are great, all you do is train, and after, you have nothing."

Indeed, most renowned foreign-born athletes in Spain first emigrated for other reasons, and then attracted attention for their talent. That's when authorities stepped in to help them gain citizenship.

But is running for a new life worth it? Crossing the Atlantic in a raft? Leaving behind language, religion, family? For these athletes the answer is an emphatic yes, but there is some nostalgia, too. "It's very hard to be torn apart," says Marhum. But, he says, "being poor doesn't give you a choice."