Surging BRIC middle classes are eclipsing global poverty

Loading...

Touting tigers, the Taj Mahal, and the towering Himalayas, India opened the 21st century with its "Incredible India" campaign to attract tourists from around the world. But the unexpected happened. A surprising new face showed up on the Indian tourism scene to fill hotel rooms and tour bus seats: Indians themselves.

They were people like Ash Narian Roy, who grew up in a rural hut but today has a PhD and works in Delhi. They are the new Indian middle class, who have begun exploring new horizons of education, culture, and leisure.

"Ten years ago," muses Dr. Roy, whose increasing ability to travel parallels the past decade's explosive growth of the middle class, "we may have gone near Shimla in our own car." But now he hires a driver to take his family into the heart of that cool summer resort in the Himalayas. And he even jets off to the beaches of Goa in the south.

The curious and free-spending domestic traveler like Roy, says Amitabh Kant, an Indian development official who wrote the book "Branding India: An Incredible Story," is an "economic savior" for India. And, to boot, Mr. Kant says, middle-class Indians are a powerful market abroad, now outspending Americans in London, for example, by 10 percent.

The "Incredible India" surprise is part of a surge of prosperity that is rapidly expanding the world's middle classes. By 2030, the global middle class is widely projected to at least double in size to as many as 5 billion – a surge unseen since the Industrial Revolution. This boom, however, is more global, more rapid, and is likely to have a far different – and perhaps far greater – impact in terms of global power, economics, and environment, say economists and sociologists.

"This dwarfs even the 19th-century middle class explosion in its global scale," noted economists Dominic Wilson and Raluca Dragusanu in a 2009 Goldman Sachs report. And they predicted, "the pace of expansion ... is likely to pick up."

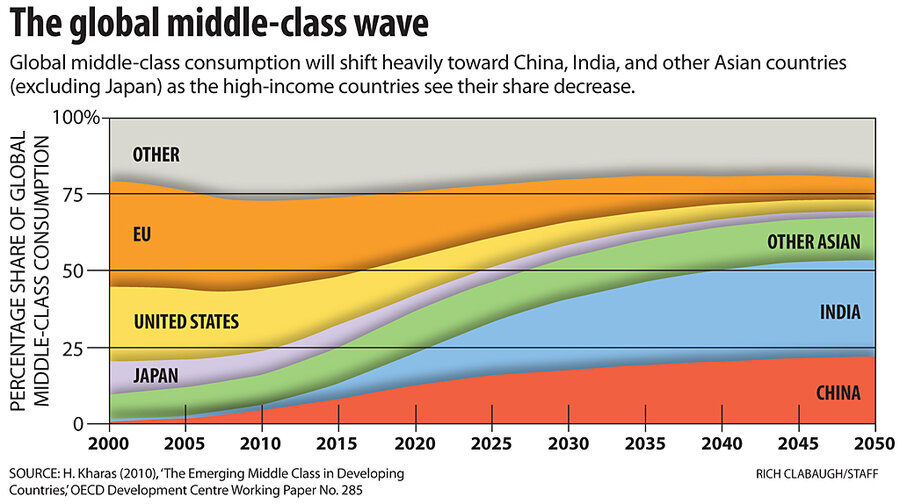

The world will, for the first time in history, move from being mostly poor to mostly middle-class by 2022, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development projects. Asians, by some predictions, could constitute as much as two-thirds of the global middle class, shifting the balance of economic power from West to East. Already, some analyses of International Monetary Fund data suggest that the size of the Chinese economy could eclipse that of the United States in just five years.

In just one example of the rising clout of this new global middle class, in a mere seven years China has gone from buying 1 General Motors car for every 10 sold in the US to becoming the American automaker's biggest customer – not to mention becoming a big competitor at the gas pumps.

But today's middle-class boom is unlike the Industrial Revolution, in which rising prosperity became a catalyst for increased individual and political freedom. Those in the emerging global middle classes – from an Indian acquiring a flush toilet at home to a Brazilian who can now afford private school to a Chinese lawyer with a new car in the driveway – are likely to redefine their traditional roles, and in doing so, redefine the world itself.

"I would expect that as the global middle class gets transformed by the entrance of hundreds of millions of Indian, Brazilian, and Chinese families, the concept of what we see as the middle-class values may change," says Sonalde Desai, a sociologist with the National Council of Applied Economic Research in Delhi (NCAER). "Historically, sociologists have defined 'middle class' as those with salaries…. I think 'middle class' is very much a state of mind."

Who are they?

From Aristotle to Alexis de Tocqueville, Western thinkers have championed the middle class as essential for prosperous, enlightened societies. They held it up as the engine for economic growth, the guardian of social values, and an impelling and protecting force for democracy.

The new members of the middle class have been praised for their work ethic, like the shopkeepers, tradesmen, and professionals who spurred the Industrial Revolution.

But they also differ in fundamental ways. They come from communal societies that rein in the individualism prized in 1800s America. Their exposure to the pitfalls of the West's extravagant consumerism often makes them more frugal and environmentally conscious. And they are hesitant – for now, at least – to risk prosperity for political freedom.

"China's rapid growth has been a kind of anesthetic that keeps political discontent manageable," says Brink Lindsey, whose book "The Age of Abundance" links America's post-World War II prosperity and its mind-opening educational opportunities to the social and political upheaval of the 1960s and '70s. "But already [in China] things are dramatically different. People have much more freedom in their lives."

That's a sneak preview, he says, of what lies ahead for developing countries – particularly the awakening giants of the middle class: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, the so-called BRICS economies.

Mall-ified consumers

Far from Rio de Janeiro's beaches and boutiques, Shopping Jardim Guadalupe is emblematic of the global economic boom fueled by Brazil, India, and China. "I want your store in my mall," reads a recent ad for the megacomplex due to open in November. It will be a hub of middle-class aspiration with not just a food court, eight anchor stores, six "megastores," and 250 smaller shops, but also a university, private high school, gym, medical center, movie theaters, and a bowling alley. More than 84 percent of the property has been sold.

Millions have long lived in Rio's poor suburbs, but only recently have they had enough money to attract a mall developer. From 2003 to 2008, 24 million people left poverty in Brazil, where the middle class now accounts for more than half of its roughly 191 million citizens. At home, they enjoy color TVs, refrigerators, washing machines, and vacuum cleaners. Half have a computer; more than a third have Internet access.

Estimates of just how big China's middle class is range widely from a low of 157 million (which would be second only to the US) to more than 800 million. With such a large middle class driving consumption, China has seen an average 15 percent growth in retail sales in recent years and is already the world's largest market for cellphones and cars (in 2009 passenger car sales increased 53 percent). India's middle class is projected by the NCAER to grow by 67 percent in the next five years, to 267 million people, or nearly a quarter of its population.

What's driving this bulge? State policies such as Brazil's increased minimum wage and India's reduced tax rates have boosted incomes. Foreign investment is giving more people salaried jobs, and those in turn are driving demand for everything from mechanics to more fashionable clothes, says economist Homi Kharas of the Brookings Institution in Washington. And more are getting better education.

That presents opportunities both for local entrepreneurs and multinationals – and could change the products available to the West.

Last year, Levi's specifically targeted Asians with its launch of dENiZEN, a new line for the "global citizen" complete with pink T-shirts that say "Chase Your Dream." In a reversal of the usual currents of global markets, dENiZEN will come to the US this summer, where Target will carry a line adapted for Americans.

There are other pioneers on this East-West route, particularly in consumer electronics, auto parts, and construction equipment, says Elizabeth Stephenson of the global consulting firm McKinsey & Company. In 2007, Finland's Nokia introduced seven low-cost cellphones in India; at least three of them are now marketed in the US. Last year, General Electric developed a low-cost electrocardiograph machine for rural India, and within weeks 500 units were en route to Germany.

"As companies have begun to sell into emerging markets, they've had to innovate – both multinationals and local companies. They've learned to do things at a much better value-to-price ratio," says Ms. Stephenson, coauthor of a 2010 McKinsey report on emerging-market growth. "Now, what you're starting to see is a lot of that innovation flow back. These new low-cost innovations are beginning to disrupt Western markets. The emerging market story is really a global story."

Within a decade, Americans could start to see some of the inexpensive cars now being launched in China, such as GM's new Baojun 630, which began selling last month starting at $10,800. But due to higher US standards for emissions and safety, along with consumer desire for sound systems and other amenities, even such cars will cost much more in America.

"At this point, they're not ready to play here with the level of expectations in the US market," says David Cole, chairman of the Center for Automotive Research in Ann Arbor, Mich. "But they are getting there. As the internationals work there, they are introducing state-of-the-art technology."

With such growth, China, India, and Brazil are projected to become among the world's top-five economies by 2050. As these nations gain clout, understanding the people behind their governments becomes crucial to discerning the world's future.

Values under pressure

Roy, the Indian traveler, directs a think tank in Delhi, where he lives in an upscale neighborhood with his wife and daughter. It's a long way from his childhood hut in Bihar, one of India's most undeveloped states.

In March, Roy flew home for his father's funeral – a 12-day ceremony involving four feasts. Electric power was available only three hours a day, and Roy's new cellphone, with a power-hogging color screen, kept running out of juice. By Day 2 he was wondering how he could escape.

"I realized that the place is so traditional I had to do all the rituals, even against my wishes," he says. He drew the line at shaving his head. His excuse: Airport security wouldn't accept his photo ID if he showed up bald.

His experience epitomizes the tension between traditional values and upward mobility that is playing out across the developing world.

But in India, the tightly knit family structure has kept values from changing dramatically and will have an effect on the character of change.

That has benefits in terms of educating children and feeling socially connected. But even as Indians become wealthier, they are unlikely to gain full autonomy to decide careers, marriages, and major purchases.

"Being independent is not really in the concept of Indian social fabric in that way that being independent is in the Western fabric," says Yashwant Deshmukh, an Indian pollster.

That's particularly true in the case of women, despite their becoming more educated.

"We have this conflicting push-pull going on – education and modernizing," says Ms. Desai. "One is getting education, one has a social status, but it is meant to be used in the service of the family rather than in individual freedom."

That contrasts with the Industrial Revolution, in which economic freedom spurred a growing sense of individualism and freedom of thought that transformed everything from gender roles to political rights.

But Mr. Lindsey is confident that today's middle-class explosion will also result in similar personal and political freedoms, though perhaps the process will be more gradual – and thus involve less upheaval.

"If you're a poor peasant, you're not in charge of anything in your life [from where you live to who you marry]," he says. "[S]o why would you presume to have anything to do with how the laws in your life are made? It's just completely out of your hands."

But people start thinking differently when they can choose their work and "it's something that requires thought and judgment, not manual labor," he adds. "Politically it manifests itself in democratization."

An opening for democracy?

But there's no political revolution waiting to happen in China – perhaps just new inklings of what it means to be a citizen.

Much of the generation joining the Chinese workforce now, who are shaping the aspirations of the middle-class bulge, were just toddlers during the 1989 Tiananmen Square uprising. Young Chinese at that time were seeking political reform to match the economic reforms introduced by the Communist Party in the late 1970s, but they were infamously put down in a massacre by the government.

Frances Sun, a Chinese senior vice president for the international public relations firm Hill & Knowlton, describes today's prosperous generation as more talented but less interested in its country's history and government. "They did not experience the hard time of China," says Ms. Sun, who oversaw the massive public relations effort for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. "They have no memory of the hard time. So they care less about politics, the country, the big issues."

It's typical historically that as people gain economic freedom, they seek a stronger rule of law, based on principles rather than personalities. While nothing like the Tiananmen consciousness is brewing today, the middle class is, however, spawning a small but growing number of activists who look beyond their own relative prosperity to the growing social inequalities that mar Chinese society.

"Volunteer organizations defending the environment or helping disadvantaged people are all set up and run by middle-class people," says Zhang Wanli of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing.

Such activities are fairly localized, if only because the ruling Communist Party does not tolerate wider networks of citizens that might threaten its control over society. "We are a long way from a full-blown civil society," says Jie Chen, a professor at Old Dominion University in Virginia. "Maybe when 50 to 60 percent of the population is middle-class they may feel more confident."

Even if many middle-class Chinese are dissatisfied with government policies, they are currently "a force for stability," says Bruce Dickson, a politics professor at George Washington University in Washington. "So many of them have benefited directly from government policies and they want them to continue."

On the personal level, though, the price of social and material success is high, says Helen Wang, author of "The Chinese Dream": "A lot of middle-class people in China are suffering from extreme anxiety … because of peer pressure to keep up with the Joneses, because of the high cost of health care for their parents and of education for their kids."

As many from China to Brazil improve their lives, global income and spending power are becoming more evenly distributed worldwide. But within individual countries, particularly in Asia, inequality is increasing because the rich are getting richer faster than the middle class can expand its share of the national pie. The growing middle classes could, however, pressure governments to adopt economic and social policies aimed at protecting them against inequality, inflation, and bubbles such as the real estate ones that have hit the US and Europe. On a more personal level, it could cause individuals to seek something more lasting than economic prosperity.

"Under the current social circumstances of big changes, people lack a sense of security," says Ms. Zhang, noting the rising popularity of religion in China. "It means they will have a greater desire and need for spiritual succor."

•Peter Ford in Beijing, Ben Arnoldy in Delhi, and Julia Michaels in Rio de Janeiro contributed to this report.