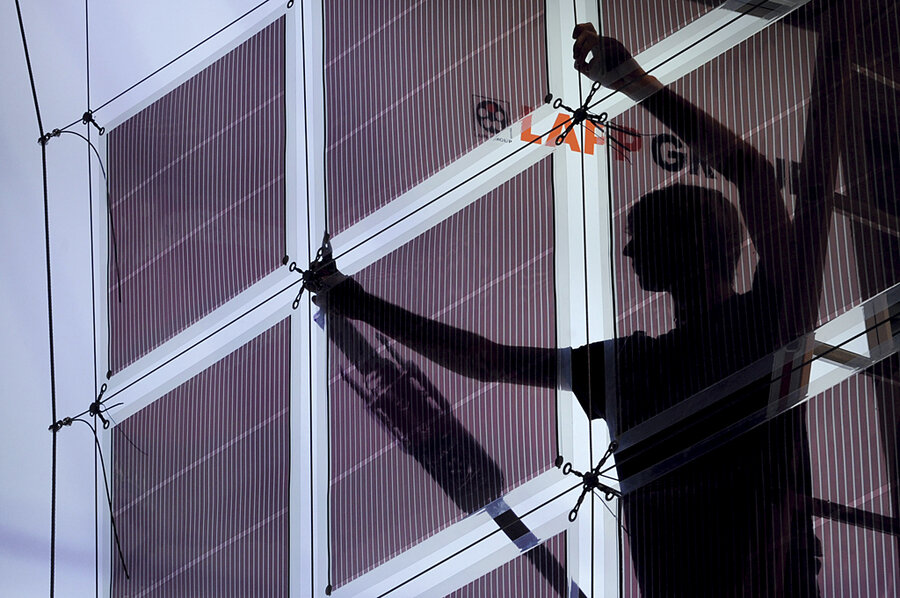

Germany hits new green-power milestone

| Berlin

It doesn't have Norway's waterfalls or Spain's sun-drenched plains. Nonetheless, Germany is inching its way up the list of renewable-energy producers: In the first six months of 2011, green energy for the first time accounted for more than 20 percent of the country's electricity production.

Given that hydroelectricity contributes only a small part, 3.3 percent, of Germany's power grid, the share of the "new" renewable energy sources – solar, wind, and biomass – has grown significantly.

"The renewables are showing their true potential," says Anike Peters, energy expert with Greenpeace Germany. "And that is in spite of numerous attempts to obstruct their progress."

The new figures, published in late August by the German Association of Energy Providers, show the share of renewable electricity sources rising by more than 2 percent in a year – a year in which the German government made not one but two U-turns on nuclear energy policy.

The government's double reversal "was a nightmare for anyone involved in planning the future of Germany's power supply," Ms. Peters says.

In October 2010, Chancellor Angela Merkel's coalition government decided to extend the life of the country's nuclear power stations by up to 14 years, thus reversing the so-called atomic consensus drawn up under her predecessor Gerhard Schröder that planned to phase out the use of nuclear reactors by 2022. Tens of thousands of antinuclear protesters took to the streets of Berlin, but failed to change Ms. Merkel's mind. Fukushima Daiichi did. The political fallout of the nuclear catastrophe in Japan had the German government return to the original target of ending the use of nuclear power within 12 years. The decision was complemented by legislation on renewable energy, aiming to extend the share of green power sources to 35 percent by 2020.

"The nuclear episode wasn't really a turning point. It was more a bump in the long road towards a sustainable energy policy," says Charlotte Loreck from the Institute for Applied Ecology in Berlin.

Ms. Loreck points out that the decision for a nuclear phase-out as well as the legal framework for the promotion of renewable energy sources have been there for more than a decade, particularly the feed-in tariffs, which guarantee providers of green energy access to the power grid and a fixed price for up to 20 years.

"The German mechanism of feed-in tariffs has given power providers and utilities the security they need to invest. It has proven to be superior to other existing promotion schemes and has been copied by countless other countries. I think Germany is on the right path," she says.

The costs for the feed-in tariffs are borne by the German consumers, currently at 3.5 cents per kilowatt-hour. And according to a new study by pollsters TNS Infratest, 79 percent of Germans are happy to pay this price or even think it should be higher.

"Most people seem to understand quite well how much value sustainable energy sources add to their lives," says Philipp Vohrer, director of the German Renewable Energies Agency, which commissioned the study. "And so they are prepared to accept new technologies even where they pop up right in front of their homes."

But Mr. Vohrer's conclusions could prove to be optimistic. While it may be true that many Germans don't mind a few extra euros on their electric bill, they are increasingly unwilling to tolerate infrastructure projects in their neighborhood. In the Schorfheide region, a popular weekend retreat for Berliners just north of the capital, you can find more and more villages openly advertising the absence of windmills as one of their features. And there are countless campaigns up and down the country against the construction of new high-voltage power lines.

It's a dilemma, admits Lars-Arvid Brischke, a senior scientist with the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research in Heidelberg. "With every new power line that is being built we see protests and legal interventions, which interrupt the planning process and delay the construction. No one wants a pylon in their backyard."

But decentralized power generation, offshore wind parks, and import of green electricity require massive expansion. "We need 3,000 kilometers of new power lines until 2025," says Mr. Brischke. "That gives you an idea of the potential for conflict."