Boston bombing reveals a new American maturity toward insecurity

Loading...

In ways both big and small, both fleeting and transformational, this time simply felt different.

On the lawn of the First Baptist Church in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston, Eve Nagler stood at a prayer vigil two days after terrorists attempted to shred the joy of Boston's biggest day with nails and BB's and bits of hurtling metal.

This, she knew, was not 9/11 – the scale, the shock, the fear were nothing like people had felt 12 years ago. Yet something else had shifted, too – something perhaps less easily definable but no less palpable to many of those at the vigil and across the suburbs that bound themselves together as "Boston Strong."

There was a calm, not only in the streets but in raw and wounded hearts.

"For myself, it's more an opening of the heart than a tearing of a big wound inside me. It feels different from 9/11," said Ms. Nagler. Dressed for a run after the vigil, her voice grew defiant when she added that the bombings would not deter her training for a coming triathlon.

What has changed since 9/11 is America itself. The Boston Marathon bombings were tragic, but they hit a city and a nation that were prepared for them, both tactically and emotionally. The calls for retribution, to apportion blame, or to lash back at Islam have all been notably muted. Even when 1 million residents were told to stay put and hunker down for 10 hours after a blazing police shootout with the suspected bombers that left one of them dead and the other on the loose, there was no panic or resentment, only resolve.

In that way, Boston has hinted at a new American maturity, say experts. Because of it, the "new normal" post-Boston might not look too different from what came before – a more robust police presence at big events, more surveillance cameras on urban streets perhaps. But like other cities worldwide that have faced the threat of bombings for decades – from London to Madrid to Jerusalem – Boston has made the more profound step of showing that a community's greatest defense against terrorism is in the determination of its people.

"Boston is showing you can take a blow like this, and you can keep going," says Stephen Flynn, codirector of the George J. Kostas Research Institute for Homeland Security at Northeastern University in Boston.

Of course, resolve was in no short supply after 9/11, and the flag planted at ground zero in New York came to symbolize the nation's determination to move on unbowed. Yet in many ways it could not. September 11 laid bare not only shocking gaps in the US intelligence network, but also the full array of terrorist groups targeting America. Quite simply, America had work to do – and new threats for its residents to process – before it could move on.

What Boston has done, indelibly, is confirm that those post-9/11 changes have become deep-rooted.

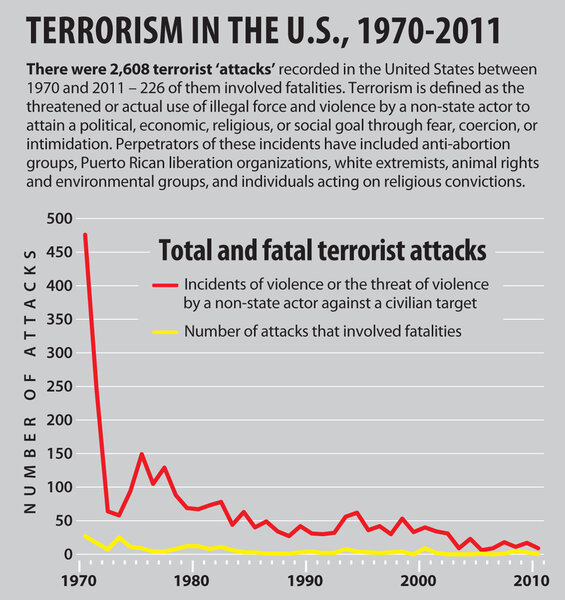

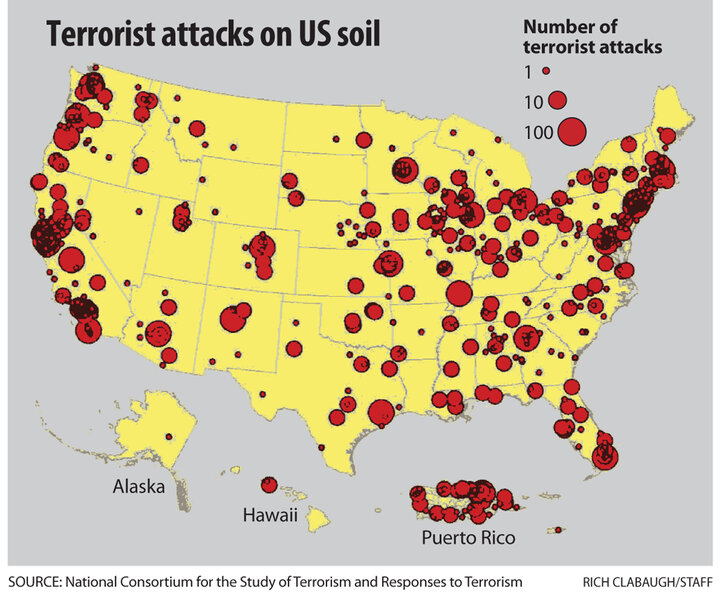

Take the number of foiled plots during the past decade – more than 150, according to Gary LaFree, director of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism at the University of Maryland in College Park. Law enforcement's success at rooting them out has given Americans confidence that authorities are doing all they can to stem the terrorist threat. Moreover, those plots have spotlighted the diversity and sheer volume of schemes against the United States.

Now, one has been carried out, and Americans are asking themselves if they want another round of disruptions to daily life – bringing airport-level security to major events, for instance – to stamp out every possible threat. The answer, so far, appears to be no.

That is no small shift. In the wake of 9/11, Professor LaFree looked at the American landscape and was filled with anxiety. From coast to coast, the number of potential targets – power plants, nuclear facilities, ports – seemed endless. His conclusion: "There's no way to protect all this stuff."

Most vulnerable of all were "soft targets" – low-security, high-density events like the Boston Marathon where terrorists (defined as those using violence to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal) – could do maximum damage with a minimal chance of being foiled.

Yet now, for the first time in the US, a soft target has been hit, and the public has maintained perspective.

"One of the lasting potential impacts of this is that Americans are being a little more realistic about the limits of what can be accomplished," says Professor Flynn of Northeastern.

"The general conversation is not a public upswell of 'We want more security to make sure this never happens again,' " he adds. "There will be a tension, but there is also a shift. It's 'Do what you can, but we can't respond in a way that's an overreaction.' "

Nancy Agris Savage would agree with that. Despite the bombings at the marathon and the gun battle that played out on the streets of her blue-collar suburb of Watertown, Mass., she doesn't want a radically new "new normal."

The morning following the apprehension of the second suspect, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, Ms. Savage, like many in her community, applauded law enforcement's response. She was watching a throng of media doing follow-up coverage on a Watertown street and said: "I'm not sure how much I want to change the way my family lives its life. We'll be more vigilant, more cautious in a way, yes. But I don't want to live more scared or suspicious."

London 'calm,' Boston Strong

To Savage, the people of London might say approvingly, "Keep calm and carry on."

Those words – and the dedication to them – saw London through the Blitz in World War II, through the Irish Republican Army bombings of the 1970s, '80s, and '90s, and more recently through the 7/7 suicide attacks by Muslim extremists in 2005 that killed 52.

Experts see hints of London's mantra in the viral Boston Strong unity response to the marathon bombings.

"Terrorist attacks are horrific, but how you respond is key," says Flynn. "You don't have to turn your lives inside out.... That is the narrative the Brits have had to embrace."

To be sure, London knows it is a terrorist target, and it has changed as a result. In some buildings, people are escorted up to office floors. Along Whitehall, the address for many government ministries, cars cannot stop and tank-resistant balustrades line the road. In some places, photography is prohibited.

But these things are simply seamless parts of London life – as much as "queuing for public transport, poor weather, waiting for lunch," says commentator Tony Travers.

"People define themselves by what they put up with living in a major city like London, which, of course, has layers of history and attacks – like the rings on a tree. People don't forget, but they live with it," he says.

Louise Weisbloom, a mother of two from Battersea in south London, acknowledges that the rhythm of life in London includes the threat of terrorism. "But I'd never leave because of it," she says.

"Living in London, security issues just become ingrained," she adds, noting that 7/7 was a reminder of the need for vigilance. "If someone followed me into work and didn't sign into security, I would say something, whereas maybe 10 years ago I wouldn't, because we probably didn't have security."

As a Londoner, Ms. Weisbloom has also come to accept the fact that she is probably being watched anytime she steps outside her door. Britain has deployed more than 4 million closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras nationwide, and those cameras were crucial in identifying the 7/7 bombers, officials say.

Now, Americans might have to decide if they are willing to put up with the same sort of surveillance for the security promises it affords. After all, the Boston bombing investigation was compelling evidence for how blanket surveillance gives terrorists no place to hide. Although most of the "surveillance" at the marathon finish line was civilian pictures and videos, the suspects were also caught by department store and restaurant surveillance cameras, and those images were described as a major break in the case.

The idea of greater surveillance on American streets might not be so tough a sell, despite America's strong streak of civil libertarianism. Some 77 percent of Americans said they would approve of government or police agencies installing video surveillance cameras in public places to prevent possible terrorist attacks, according to a 2009 CBS News poll.

For now, the mandate seems to be to ramp up security, but in ways that don't unduly disrupt daily life.

It will be up to law enforcement agencies whether to raise the level of security, says Martin Reardon, vice president of The Soufan Group, a security consultancy. He points to CCTV cameras, as well as more K-9 patrols and police sweeps at big events, as potential ways forward.

Security is not always obvious

Discreet security is a lesson Spain has internalized in its decades-long struggle with terrorism. Before the 2004 attack by Muslim radicals against a Madrid railway hub, which killed 191, the country faced a half century of bombings by the Basque separatist group ETA, which killed 800 people before agreeing to a cease-fire in 2010.

Security in Madrid is intense but not noticeable, aside from X-ray machines in some public buildings and the video cameras above the streets.

"A big part of the security we feel has to do with discreet prevention," says Mikel Buesa, a terrorism expert at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. "Of course security is there, and significant resources are invested. But it's not routinely made public, which makes its perception nil."

Working with quiet restraint has meant "infiltrating organizations, gathering intelligence, and sharing information with other countries," says Francisco Javier Elzo, a sociologist and professor emeritus of Deusto University.

Creating connections with communities that might have members susceptible to radicalization is one of the lessons from the sarin gas attack in Tokyo. On the morning of March 20, 1995, five members of the Japanese doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo boarded subway trains carrying commuters into the capital's political and administrative centers. Minutes later, using umbrellas with sharpened tips, they punctured bags filled with liquid sarin – a nerve agent developed by the Nazis. The gas killed 13 and shattered the public's confidence in their country's reputation as one of the safest in the world.

The investigation into Aum Shinrikyo, amid intense media scrutiny, revealed how authorities had allowed followers of an apocalyptic cult to develop and stockpile sarin and other weapons of mass destruction. Revelations that the cult, registered as a religious legal entity, had been behind a string of other crimes, including a 1994 sarin attack on the northern town of Matsumoto in which eight people died, prompted a debate on how to reconcile constitutionally guaranteed religious freedoms with the safety of an increasingly nervous public.

A special surveillance law, passed in 2000, allows the police to monitor the activities of offshoots of Aum Shinrikyo, but some worry about the group's isolation.

"Human relations are weak in Japan, and that can act as a breeding ground for cults and new religions," says Yoshihide Sakurai, a professor at Hokkaido University who specializes in cults and new religions.

"There are people we don't understand, who may not think the same way the rest of society does or share our ideas about their purpose in life. There is no exchange between mainstream society and these groups, and that's where the danger lies."

Lockdown: a terror 'success'?

The Boston bombing case underscores that point. Cosmopolitan Cambridge, Mass., would hardly seem to be a breeding ground for cultural isolation and hatred. But according to reports and court documents, Mr. Tsarnaev and his older brother, Tamerlan, masterminded their own terrorist plot with help from online videos while living there. It is a post-9/11 parable of American extremism, as terror networks such as Al Qaeda are increasingly eclipsed by self-radicalized "lone wolves" who often operate independently.

"Patterns of extremism evolved after 9/11," says Peter Romaniuk, a terrorism researcher at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. "These guys don't need to attend an Al Qaeda training camp anymore."

For a police department seeking to find potential terrorists, he adds, "that makes the task extremely difficult."

Since 9/11, the New York Police Department has been a leader in counterterrorism. But its experience shows the challenges of trying to keep up with the constant mutations of extremism. In the early years after 9/11, the department was lauded for reaching out to communities that had members that might become radicalized. "NYPD won a lot of commendation," Professor Romaniuk says.

But as terrorism became harder to track, the NYPD turned to more invasive tactics. An Associated Press investigation detailed programs that profiled Muslims, tracking where they ate, prayed, and worked, even if they were not suspected of being a threat.

"There is a very fine line between trying to prevent people from becoming extremists and engaging in surveillance activities," says Romaniuk.

Even Boston has not been held above criticism for its decisions in the marathon bombing investigation. The decision to shut down much of the metropolitan area as authorities searched for Tsarnaev was a mistake, says Professor Elzo, the Spanish sociologist. "Never could these terrorists have imagined they would have been so 'successful': an entire city paralyzed to hunt them and the entire world tuned in to see it unfold," he says. "What an amazing motivation for future terrorists."

Though law enforcement is likely to come in for criticism no matter how it deals with terrorism, counterterrorism efforts in Russia have come in for particularly harsh condemnation. To experts, they are an example of too heavy a hand. For many Russians, they are seen to be as threatening as the acts of terrorism themselves.

In 2002, when Chechen separatists stormed the Dubrovka Theater in Moscow and held the audience hostage, Russian authorities fed a special gas into the theater to knock everybody out before rushing in and gunning down all the terrorists. Unfortunately the gas also killed about 130 of the hostages. Then in 2004, Chechen militants seized a school in Beslan with about 1,200 hostages, including almost 800 children. On the third day, Russian special forces stormed the school, using tanks, heavy weapons, and rocket launchers, killing 334 people, 186 of whom were children.

Yekaterina Moryeva was a hostage at the Dubrovka Theater – a musician who lost her husband, also a musician, in the siege. She was left with three children and no answers.

"I was in shock and had to take tranquilizers for the first half a year after the theater siege," she says. "I remember living as if in a fog for the first five years. For the first half year I slept with my husband's old shirt."

"But my questions to the Russian state remain," she adds. "If my son asks me why his father died, I cannot answer. Until now it is not clear to me why it happened the way it did, why my healthy, strong, beloved husband died. Nobody has ever explained in a satisfactory way to me. If he had been killed by a terrorist's bullet, it would not be quite so painful."

More broadly, Russia has been seen as slow to increase security despite repeated terrorist strikes. In 2004, two Chechen bombers penetrated Moscow's Domodedovo Airport and blew up two jetliners in midair, killing hundreds – but despite investigations that showed multiple security failures at Domodedovo, security measures were not instituted.

In 2010, a double suicide bombing by "black widow" terrorists – wives of rebels killed by Russian security forces – left 40 people in the Moscow subway system dead, while another suicide bombing at Domodedovo in 2011 killed 35.

Initially, then-President Vladimir Putin used terrorism to further his political agenda, changing electoral law in 2004 so regional governors would be appointed by the Kremlin, not elected. It's only since 2011 that the strict security meas-ures standard at Western airports have been adopted in Moscow.

"We've all noticed that security in the airports is much better," says Gennady Gudkov, a former KGB officer and Duma deputy, now a security expert. "A lot has been done lately to put us ahead of the curve, in case fresh terror strikes occur."

Treating terrorism like crime

Before Boston, the zest to be vigilant against terrorism had perhaps begun to wane in the US. As years passed without a major attack against a civilian target, officials in metropolitan areas of the US were beginning to lean away from counterterrorism.

On one hand, it brought results. "Part of the reason we haven't been seeing plots succeed is the amount of resources that were thrown at it," says LaFree, at the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism.

But it was expensive.

"A lot of politicians are asking us, 'Why are we spending so much on [preparations] for terrorism?' " says Seth Jones, a terrorism analyst at RAND Corp. in Arlington, Va. "There has been a growing trend toward focusing less on terrorism as a problem and focusing on other security issues" like crime or cyber-espionage.

"Boston has rebalanced that debate a little," he adds. "This is still an issue that is a challenge."

He and others don't expect the pendulum to swing back to post-9/11 highs. Rather, they see a new equilibrium developing that puts the persistent threat of terrorism in a more realistic context.

"This is not a war. This is more like crime – we're going to manage it, not eliminate it," says LaFree. "So let's put it in with crime [as a priority] as opposed to putting it on a 'wartime footing.' "

Terrorism tinges daily decisions

In the Israeli town of Sderot, situated within rocket range of the Gaza Strip, terrorism took the form of a quasi-war with Palestinian neighbors. Yet the lessons learned there daily are not so different from those learned on Boston's Boylston Street at 2:50 p.m. on April 15.

At first the rockets were crude and the attacks intermittent, but by 2006 as many as 80 rockets a day were falling on the town. With Sderot only a half mile from the Gaza border, citizens have just 15 seconds' warning. During such escalations, mothers in Sderot would debate whether to put seat belts on their children, because it often took more than 15 seconds to unbuckle them and get to the nearest shelter. If they were caught outside, the mothers would lie on top of their children to protect them.

Yet thanks in part to how the community has rallied together, home prices in Sderot have increased 200 percent during the past four years – a spike nearly four times greater than the national average, driven in part by young couples looking to settle here, says Kfir Asulin in the local Re/Max office.

Moreover, the local Sapir College has more than doubled its enrollment and is now the largest public college in Israel.

"They wanted to turn Sderot into a ghost town.... Our answer was not to run away, but to build," says Mechi Fendel, a computer programmer whose husband founded an ever-expanding yeshiva (a college for Judaic studies) that proudly displays on its roof an enormous menorah made from Qassam rockets.

Like others, she cites faith as a pillar of her strength. "Spiritually we're alive and well and nothing is going to stop us."

Some 15 percent of the population suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. But Ms. Fendel says that by dealing with the persistent attacks in a "normal, intelligent" way, her seven children have been able to remain calm and help others. At age 13, when her daughter was hosting a day camp during Passover, she successfully ushered 25 toddlers into a bomb shelter when the siren went off.

Those too old or infirm to sprint to one of the concrete bus stops along Sderot's palm-lined streets in the case of a rocket attack often choose to stay home near the safety of the bomb shelters that nearly every building in the city has. During the latest escalation, in November 2012, the nonprofit Reut Sderot Association called every family – many of which were missing men who had been called up for reserve duty – and helped those who needed it with grocery shopping and other chores.

"Being part of a community is very helpful," says Odelia Ben Porat, a mother of five who works with Reut and moved to Sderot in 2006, just weeks before a major escalation that caused her and her husband to seriously consider leaving. "I think that's the reason we decided to stay after all."

Reflecting on Israel's lessons in fighting terrorism, Yossi Klein Halevi, a senior fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, says: "If America is really going to deal with terrorism in an effective long-term way, it has to be with quiet determination."