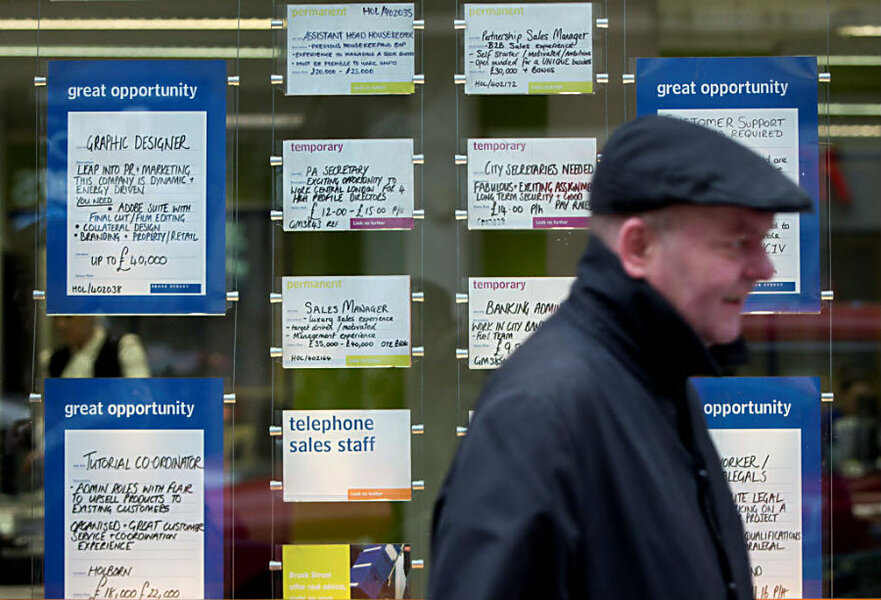

UK job market improves. No 'Brexit' effect?

Loading...

After Britain voted in June to leave the European Union, economists feared a “Brexit effect.” The jobless rate would increase, as corporations moved to mainland Europe or Ireland.

Nearly three months after the referendum, the roaring unemployment some economists predicted has been just a purr. In fact, the unemployment rate has improved, and a historic three quarters of Britons who can work have jobs, according to a survey the British Office for National Statistics (ONS) released Wednesday.

The country’s unemployment rate for May to July fell 0.6 percent from a year ago, from 5.5 percent to 4.9 percent, according to ONS. The employment rate was 74.5 percent for those three months, with 559,000 more Britons employed than a year ago.

The survey has upset dire forecasts about the immediate blowbacks of Brexit. But economists are divided over what this means in the long run. Some argue the survey contains other indications the worst is yet to come, such as the slowdown in wage growth. Others say it shows the resiliency of the British economy.

“Clearly there are risks that this is the calm before the storm. But, for now, there don’t seem to be any storm clouds on the horizon,” Alan Clarke, an economist at Scotia Bank, told The Guardian. “It is business as usual after the referendum. Firms have not stopped hiring. Blaming the slower wage numbers on Brexit is putting the cart before the horse because the wage data lags [other measures of the economy’s health] by a considerable margin.”

Because the survey was conducted from May to July, it carries just one month of data following Britain’s referendum on the EU June 23. ONS interviewed 40,000 households for the survey it performs every three months.

Britain is the second largest economy in Europe, and the fifth largest in the world, as measured by its gross domestic product.

Some of the results of ONS’s Labour Force Survey are good news. The employment and unemployment rates show jobs were “resilient” after the referendum, analysts told BBC. It also boosted the pound 0.13 percent, as it rebounded from a two-week low Tuesday, following the release of UK inflation data, according to The Telegraph.

But some economists said it’s no cause for celebration. They pointed to the slowdown in wage growth. Wage growth decreased (including bonuses) from 2.5 percent to 2.3 percent.

Others critics say the boost in employment is deceptive.

“When you scratch beneath the surface, today’s labor market figures are not as robust as they first appear,” Samuel Tombs, chief British economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, told BBC. The rise in people in work “remains supported by surging self-employment … the strong growth also reflected a shift towards part-time working; total weekly hours rose by just 0.3 percent between April and July.”

While the results of the survey are mixed, it counters one firm’s analysis in July of a coming “Brexit effect,” as reported by Max Lewontin for The Christian Science Monitor.

A closely watched indicator of the country’s economic health known as the purchasing manager’s index (PMI), produced by the research firm IHS Markit, dropped to 47.7 percent. That’s the lowest level since April 2009, when Britain was in the throes of the global financial crisis, the firm says.

"The only other times we have seen this index fall to these low levels, was the global financial crisis in 2008/9, the bursting of the dot-com bubble, and the 1998 Asian financial crisis," Chris Williamson, chief economist at IHS Markit, told the BBC. "The difference this time is that it is entirely home-grown, which suggest the impact could be greater on the UK economy than before.”

Both manufacturing and the service sector, which includes businesses such as transportation, restaurants, and computing and makes up nearly 80 percent of Britain’s economy, saw notable declines in the PMI survey, the Financial Times reports.

When British telecom giant Vodafone announced in late June it was considering moving its headquarters out of its home country, other economists predicted other companies would follow.

“It will be more a movement on the margins than big, discreet changes,” Thomas Sampson, a professor at the London School of Economics (LSE) who specializes in international trade, growth, and development, told The Christian Science Monitor. “We might see some companies like Vodafone relocating their headquarters. We might see others investing less in the UK,” he added, mentioning, as an example, a financial firm relocating jobs from London to Paris, Frankfurt, or other cities in the Eurozone.

But a BBC economic editor says the latest survey results could also show the government is pushing public employees on to the private sector.

"Yes, employment is at record levels, but it is the private sector that is on the up," wrote BBC editor Kamal Ahmed. Public employment is down to 5.33 million, the lowest level since ONS started collecting figures in 1999.