Niger coup: Can Africa use military power for good?

Loading...

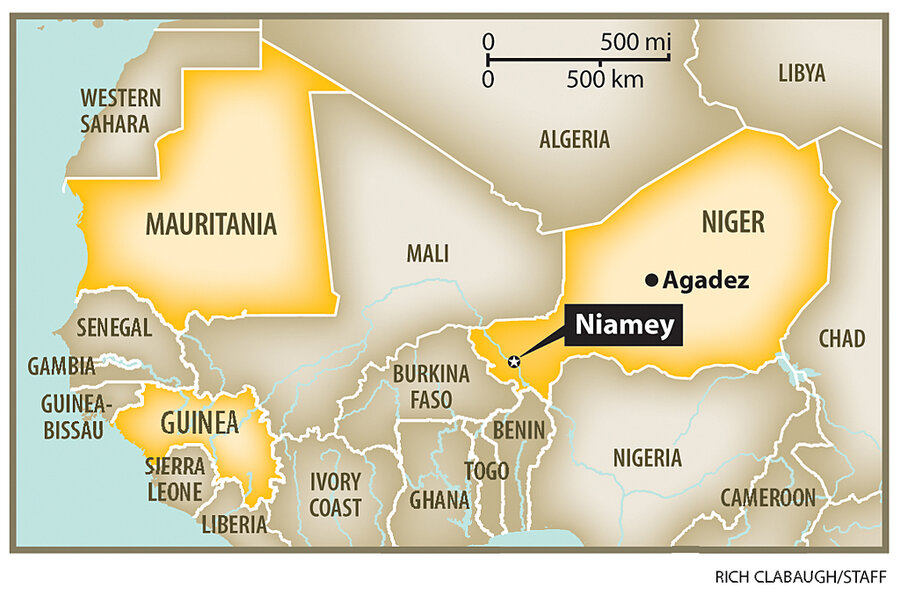

| Niamey, Niger

Weeks after the Feb. 18 coup in Niger, the gates of the presidential palace still gape with holes blasted by mutinous commandos. No one knows when there will be a new leader to order that the debris cluttering the lawns be cleared.

For now, a military junta is still calling the shots.

On its face, the latest military overthrow of an elected African leader is yet another setback for democracy in West Africa. There have been other coups on the continent, and the justification is often that the current leader is corrupt or running roughshod over the Constitution. The ouster of strongman Mamadou Tandja, who overstayed his electoral mandate, is once again raising the question: Is there such a thing as a "good coup"?

"As democratic people, we can't cheer a military coup d'état," says Ali Idrissi, president of a coalition of Nigerien nongovernmental groups working for transparency in the impoverished country's lucrative oil and mining industry. "But in reality, deep down, we are cheering it. For us, it's a good coup d'état."

Many blame mounting insecurity and epidemic poverty in the landlocked West African country on the failures of Mr. Tandja's 10-year rule.

Despite vast reserves of oil and uranium, the United Nations considers Niger the world's least developed country, ranking just below Afghanistan.

Calling itself the Supreme Council for the Restoration of Democracy (CSRD), the military junta has sought to allay fears since the coup, vowing to organize elections, tighten security, and prioritize an overhaul of the country's graft-ridden extractive industry.

On March 1, junta leaders appointed a 20-member cabinet to run the country until elections can be organized, but have not yet set a timetable.

So far, the approach seems to be working as far-flung factions that suffered under Tandja's rule express cautious optimism for improved conditions.

"There is a little hope now," says Aghaly ag Alambo, the leader of the 2007 Tuareg rebellion affecting millions of largely Tuareg desert nomads in the volatile north.

Formerly Niger's most wanted man, Mr. Alambo traveled to the capital March 14 for the first time in four years to open negotiations with the CSRD. "We will try to build peace," Alambo said, clad in white flowing robes in his hotel room in Niamey. "But it is often easier to make war than to build peace."

Nuke components for Iran?

Lucrative uranium mines and oil wells located on traditional pastoralist lands have brought few benefits to the Tuareg and other indigenous nomadic populations, who say land grabs under Tandja are ruining their environment and jeopardizing their livelihoods.

Many here feel that the ouster came at a decisive moment.

After Tandja's term mandate expired Dec. 22, 2009 (and he changed the Constitution), international censure and a halt in nonhumanitarian aid weakened Tandja's grip on power.

He sought to forge last-ditch alliances just days before the coup, announcing he intended to grant contracts to mine uranium – the core component in nuclear energy – to Iran and North Korea.

Other 'good coups'

Some observers call Tandja's ouster a countercoup, the first coup having occurred when Tandja unilaterally extended his elected term.

And while a countercoup may ultimately be a step toward democracy, it's often a slippery slope. Examples of military juntas in other West African states show it is far easier to remove a reviled regime than to restore constitutional order. Coup leaders and dictators often justify their actions on the basis of "Father-knows-best" stability.

International observers heaped praise on the junta in Mauritania for following the 2005 ouster of a dictatorial president of 21 years with elections deemed free and fair. But one year after those elections, junta leader Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz staged yet another coup against the new head of state. Mr. Aziz himself is currently the elected president of Mauritania.

In December 2008, Army officers in Guinea calling themselves the National Council for Democracy and Development seized power hours after the death of the president. A crackdown on civilians ensued, culminating in a massacre of 150 protesters last September.