How moderate Muslims in Africa view NYC mosque debate

| Dakar, Senegal

Suburban Point E, on whose cobblestone backstreets Senegalese-American R&B roué Akon passed his boyhood years, already has a mosque. Several, actually, each megaphoning prayer songs across balmy Ramadan soirées. So, locals wonder, why shouldn't downtown New York City get another mosque, too?

The question may seem trivial, coming from one of Africa's smaller nations, but America's controversy over the interfaith community center proposed by Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf has implications for the United States' ability to thwart terrorism and defeat Al Qaeda. And Senegal, with a 95 percent Muslim population, represents a pivotal buttress in that campaign, say US military operatives. With Islamic fundamentalism triumphing in neighboring Mauritania and northern Nigeria, strategists see Senegal as a critical junction for US dialogue with the Muslim world.

“Islam in Senegal is tolerant, and we expect that tolerance in return," says Souleye Diallo, director for a study abroad program here.

But lately, Senegal’s FM talk shows and private press have been appalled by America's debate over the mosque near ground zero, protests against Mr. Rauf, a Manhattan taxi passenger's attack on his Muslim driver, and sneers that Muslims worship “a monkey god” (that was former Tea Party spokesman Mark Williams).

4 mosque battles brewing across US

Land of intolerance?

Mr. Diallo says Senegalese aren't seeing tolerance in the charged debate over the proposed Islamic community center about two blocks from the former World Trade Center. Nor did he personally feel it when he visited New York City earlier this month. While waiting to board the Staten Island Ferry for an iconic boat ride past the Statue of Liberty, he says he was profiled, frisked, and bag-searched in front of his outraged daughter.

He cautions that it was a one-off experience. “Senegalese go to America because in America, they can have their rights respected, and their freedom of movement to be entrepreneurs,” he says. “It’s not like in France, where you can be asked for your papers wherever you go.”

Allowing a mosque near ground zero, says Diallo and other Senegalese, would restore America's image as a place of opportunity while also allowing Muslims to feel accepted. Islam pervades Senegal’s Sahelien milieu, as does the hope harbored by youths to travel to America and prevail as capitalists on a stage like New York City.

Their impressions are not to be taken for granted. Senegal's second-biggest export (after its desert-farmed peanuts) might be New York's entrepreneurial class of Senegalese-American immigrants, studying business, driving night taxis, running Harlem restaurants in the Le Petit Sénégal neighborhood, reinvesting millions of needed dollars into Senegal's agrarian economy, and even selling "Never Forget" snow globes around ground zero itself. After all, it was a Senegalese souvenir salesman named Aliou Niasse who was the was the first to see smoke, and then call 911, when a Pakistani-born banker tried to car-bomb Times Square in May.

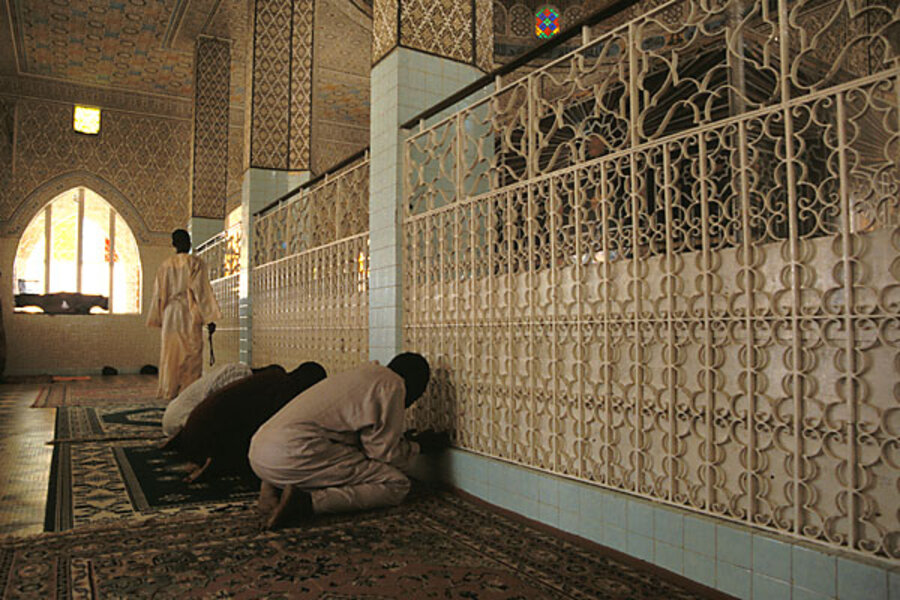

“It would be good to have a mosque there, to create dialogue between all religions,” says Mamadou Mbao, an unemployed young man sitting curbside his mosque. “If it’s controversial, then they must build one church and one mosque, right there in the same place. That’s fair.”

“I don’t understand,” adds his friend Mustafa Ndiaye. “If they’re saying it could become a terrorist command center, isn’t America a powerful country? If it becomes a terrorist command center, couldn’t American just shut it down?”

Case closed, for Mr. Mbao and Mr. Ndiaye. Then they asked this American journalist for help in scoring two green cards.

Mosque helps US image

Human rights activist Daha Cherif Ba says he can appreciate America’s anxiety surrounding Islam. “If Americans bombed us, you wouldn’t be welcome here, either,” he says.

Mr. Ba thinks the mosque near ground zero should be relocated. “Minorities must respect the sensitivities of the majority,” he says.

But Mbao, Ndiaye, Diallo, a gathering of bearded men in a mosque, two students, a teacher, a young man reclining across a wooden bench, and a university professor all disagreed.

“For us, it would be a blessing to have a mosque there, where Muslims could pray for the deceased,” says Diallo, the study abroad director. “I understand the grievances, and yes, there were Islamists behind the attack, but the way to heal is to accept people’s prayers.”

But he says he knows the reality of America's news cycle and heavily charged political scene.

“America’s politicians,” he adds, “are thinking about re-election, not how to heal.”