Delaware-sized lake discovered beneath Kenya desert

| Nairobi, Kenya

Scientists using technology for discovering oil have found a vast underground water reservoir in one of Kenya’s driest regions that could supply the country's needs for nearly 70 years, potentially turning arid zones into lush farmlands.

The new reserves are located in a basin in the extreme northwest that has a surface area the size of Delaware, and is estimated to hold billions of gallons, nearly nine times Kenya’s current reserves.

Almost half of Kenya’s 41 million people have no access to clean water, and farmers in arid areas struggle to raise crops without adequate irrigation.

Scientists say it is possible that, along with water run-off from surrounding hills and plains that replenish the aquifer, the newly discovered resources could fulfill the country's water demands indefinitely.

Tapping the new reserves in the basin, located in Kenya's northern Turkana region, may allow for vast new zones of farmland in landscapes where today even the hardiest plants struggle to survive.

“The news about these water reserves comes at a time when reliable water supplies are highly needed,” Judi Wakhungu, cabinet secretary at the Kenyan environment, water, and natural resources ministry, said in a statement.

“This newly found wealth of water opens a door to a more prosperous future for the people of Turkana and the nation as a whole," Ms. Wakhungu added. “We must now work to further explore these resources responsibly and safeguard them for future generations."

The hitch

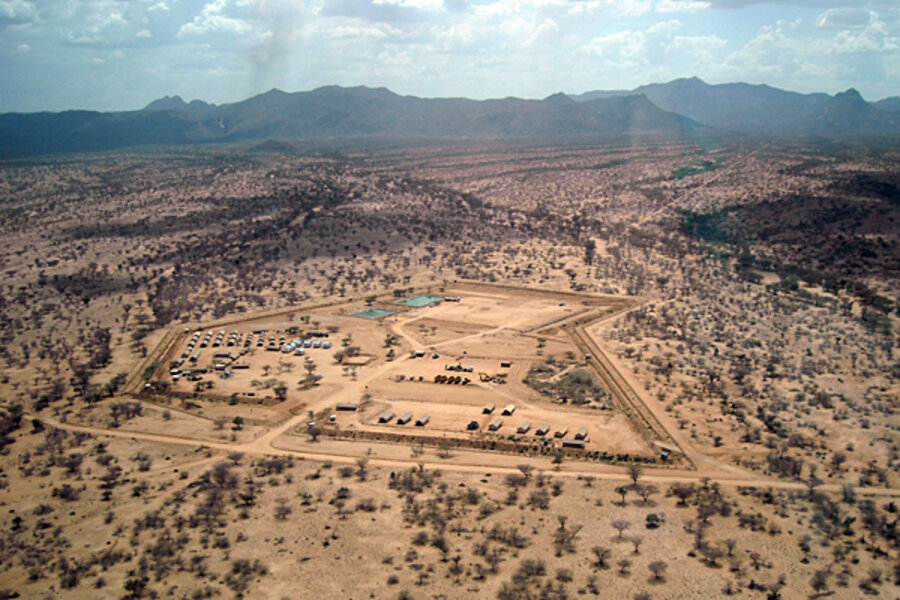

If there is one hitch, the basin is in a remote area in the extreme northwest. It lies close to Kenya's borders with South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Uganda in an area sparsely populated and prone to conflict over existing scarce resources.

The land that lies above the reservoir is among the most hostile in Kenya. There are few roads or electricity supplies, and the Turkana, Samburu, and Pokot tribes that live there are regularly at war with each other.

The border area between Kenya, South Sudan, and Ethiopia, known as the Ilemi Triangle, has never been officially delineated.

Constructing, fueling, and maintaining boreholes, and building pipelines to bring the water supplies to remote communities, can pose significant difficulties.

Who found it?

The discovery was made by researchers from a Texas-based company, Radar Technologies, with assistance from the Kenyan government and Unesco. The team layered satellite, radar and geological maps on top of each other and then used seismic techniques developed to find oil, to identify the reservoir.

“It is important to say that these are early estimates, and these resources must be managed well in order that they benefit the people of Kenya,” says Mohamed Djelid, Unesco’s East Africa director. “But if all goes well, we can say that this really is a game changer.”

Kenya’s government will now carry out further drilling in areas surrounding the sites where the new water supplies were first drawn to the surface, to gather more data on their full extent.

In the past there have been similar announcements of massive new water finds beneath Africa’s driest areas. In 2007, scientists said that they had identified an underground “megalake” in Sudan’s war-torn Darfur region that was 10 times the size of the Kenyan discovery, but its bounty has yet to be tapped.

“Knowing there’s water there, and then getting it to the surface, are two different things,” says Brian McSorley, a water expert at Oxfam in Nairobi. He added that, "There will need to be decent follow up studies and then proper investment to ensure that these newly-discovered resources benefit the poorest people.”

The aquifers lie as deep as 1,000 feet, which poses significant technological and cost challenges compared to shallower reserves, Mr. McSorley says but notes that, “Having said all that, the figures are encouraging and I think this needs to be cautiously welcomed.”