Can 2,500 more African UN troops contain South Sudan carnage?

Loading...

| Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

The United Nations Security Council has approved three battalions of East African peacekeepers to try to prevent further fighting between South Sudan government forces and rebels as they vie for control of the country's oil-rich east.

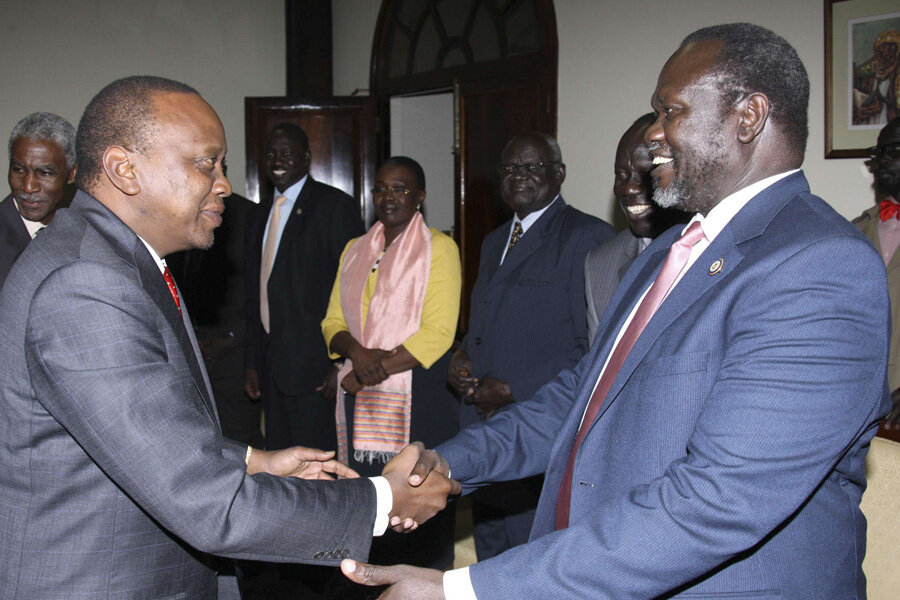

The 2,500 troops from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Rwanda should begin deploying in the world’s newest nation within weeks. Their aim is to enforce the May 9 truce agreed to by President Salva Kiir and his rival ex-Vice President Riek Machar, according to Getachew Reda, adviser to Ethiopia's prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn.

Officially, the soldiers are to protect teams of monitors from the region whose mission is to verify reports of violations of a temporary cease-fire.

The subtext is that mediators hope the battalions will prove an intimidating enough presence to deter fresh assaults. Such an intervention may be the only way to stop hostilities, with the start of peace talks looming on June 5, according to many observers such as the European Union.

Another hope behind what is essentially a regional intervention overseen by the UN is the withdrawal of Uganda’s military. Ugandan forces played an important role in halting rebel advances at key points in the South Sudan conflict, but negotiators have criticized Mr. Machar's rebels for using the presence of Ugandan troops, which aid Mr. Kiir’s government, as a stalling tactic in current talks.

Some longtime Sudan-watchers, however, describe the international efforts as too weak amid a brutal conflict in a fledgling nation with powerful ethnic allegiances. They also worry about the strong self-interests of regional African states that are sending troops.

Canadian scholar John Young, author of "The Fate of Sudan: The Origins and Consequences of a Flawed Peace Process," says that while the UN has a mandate to act, that it has not begun to "seriously and critically assess its weak performance in South Sudan and in particular its failed leadership in the field. Increasing the size of the [UN] field deployment in the country does not begin to address those problems."

Fighting in South Sudan broke out in the capital Juba in mid-December, after Machar and other leading government figures challenged what they say was Kiir’s increasingly despotic rule. Kiir responded by accusing them of plotting a coup.

Forces loyal to Kiir, a member of the Dinka ethnicity, then targeted Nuer people – the ethnic group to which Machar belongs – in the capital, according to the UN. This led to a Nuer uprising in Upper Nile, Jonglei, and Unity states, with the fugitive Machar becoming the figurehead of the rebellion.

The UN has accused both sides of targeted ethnic killing and UN and other NGO agencies have documented a surprising scale of atrocities for such a short conflict.

The local African troops will be part of the existing UN mission in South Sudan, whose mandate was tweaked by the Security Council this week to focus on civilian protection by some 12,000 soldiers and police, rather than the original purpose of state-building.

The idea for the regional force came from peace envoys at the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a bloc of East African countries overseeing negotiations between Kiir and Machar’s delegates.

The UN mission is now mandated to use “all necessary means” to protect civilians through “proactive deployment and active patrolling,” particularly if the government is failing to do so, according to the resolution.

The peacekeepers will face heavy rains, terrible roads, and a fragmented conflict where commanders are only loosely in control of militias. They may also face hostile rebels.

The new resolution says that oil fields are one of the areas peacekeepers may deploy if “appropriate.” This was rejected by a spokesman for the insurgents, Lul Ruai Koang, today, who said it will help Kiir continue to use oil revenues to fund the war.

“By stepping in to protect oil installations on behalf of the government, UNMISS will have sided with one of the parties to the conflict and inevitably becomes part of the problem not the solution,” Mr. Koang said.

The latest initiative to end the civil war comes a week after donors at a conference in Oslo, Norway pledged $600 million to try and prevent famine in South Sudan. The three regions where fighting has been concentrated were the most short of food before the outbreak of war.