Why tiny Gambia's political transition holds outsized meaning for many Africans

Loading...

| Johannesburg, South Africa

No sooner had The Gambia’s outgoing president Yahya Jammeh had left the country Saturday evening, sealing the country’s first transition of power in more than two decades, than a hashtag began trending on Twitter in much of Africa: #LessonsfromGambia.

“Time is up for dictators in Africa #LessonsfromGambia,” wrote one user. “The Power of the People Is Greater Than the People in Power #LessonsfromGambia,” wrote another.

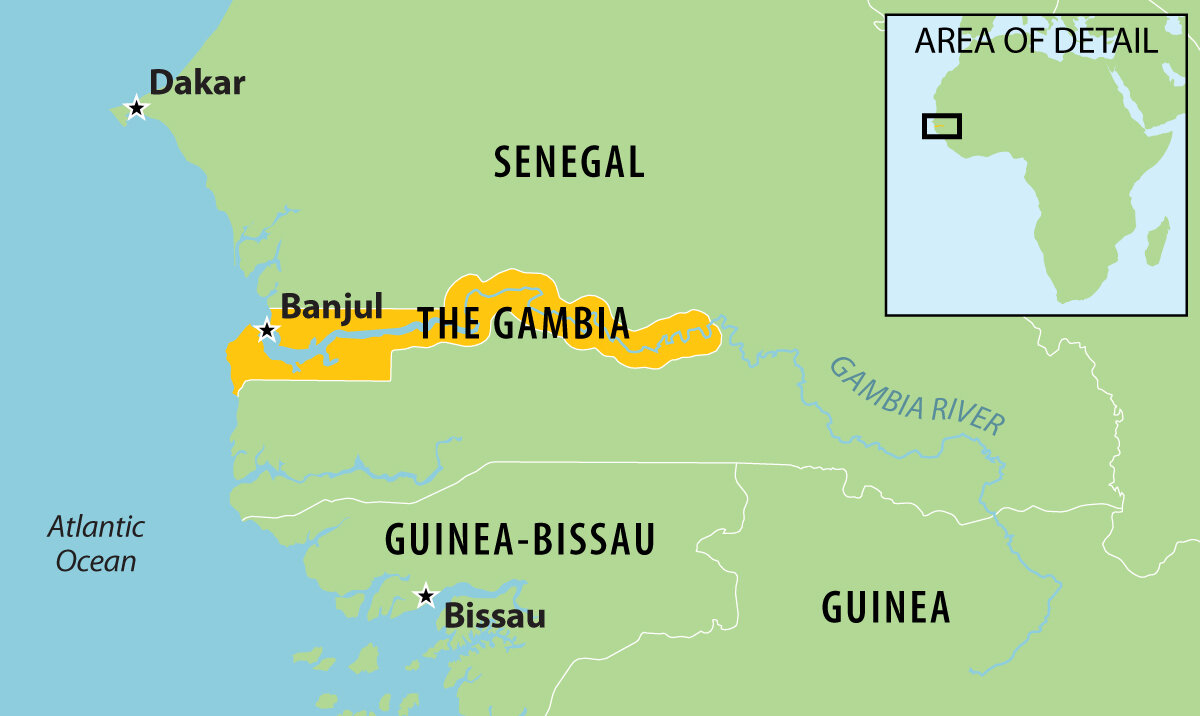

But if the departure of Mr. Jammeh – who had ruled the tiny country buried inside Senegal since taking office in a 1994 military coup – provoked many congratulations, equally exciting for Africa’s Twitterati was how it had happened.

The Gambia’s transition had been made possible in large part by the deft intervention of its neighbors in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), who over the past two months have shuffled between negotiations and the threat of military intervention to convince an often recalcitrant Jammeh that he had no choice but to go.

On a continent where regional bodies have often failed – by accident and by design – to shelter democracy, that seemed for many here a watershed moment.

"#ECOWAS set the blueprint that #Africa's affairs can be solve[d] within #Africa, without unfavourable western conditions #LessonsFromGambia,” commented one Twitter observer. “If regional blocks in #Africa take the same lead as #ECOWAS did in #Gambia, dictatorships will become a thing of the past.”

Those tweets also speak to the outsized symbolic significance of The Gambia’s transition, which has felt to many in Africa like something far bigger than a changing of the presidential guard in the continent’s smallest mainland country. It seemed at times a warning for other longstanding dictators on the continent, which is home to seven of the world’s 10 longest-serving rulers.

“We don’t live in isolation anymore, and the age of impunity is slowly coming to a halt,” says Jeggan Grey-Johnson, coordinator for communication and advocacy with the Open Society Foundation’s Africa Regional Office in Johannesburg and a Gambian political analyst. “The lesson here – and I think other long-serving heads of state will stand up and take note – is that with people power, combined with adequate response from the regional communities, democracy on the continent will be consolidated.”

Let us help you step down

ECOWAS took an early and energetic interest in The Gambia’s transition. In December, just days after Jammeh first conceded the election – then abruptly retracted his admission of defeat – a high-level delegation touched down in Banjul to talk the president down from his political precipice.

The team spanned a wide range of perspectives. It included the leader of regional powerhouse Nigeria, Muhammadu Buhari – who had himself been part of his country’s first democratic transfer of power two years before – alongside presidents of two countries that had experienced violent political conflict and military intervention: Liberia’s Ellen Sirleaf Johnson and Sierra Leone’s Ernest Bai Koroma. Also present was one newly ousted president, John Mahama of Ghana, to show “there’s life after losing the vote,” says Paulin Maurice Toupane, a researcher with the Institute for Security Studies in Dakar, Senegal.

That initial negotiation fell through, but the message was clear: the region was watching.

“It helped very much that those regional actors presented a united front and a common understanding of the situation – that [Adama] Barrow was the victor and Jammeh must go,” Mr. Toupane says. “It meant they could speak as one voice and also helped them to earn the support of international bodies like the UN and [African Union] as well.”

Seven thousand ECOWAS troops entered the country Thursday, where they met no resistance from a Gambian military thought to have an active fighting force of approximately 1,000 soldiers. The troops are still in the country indefinitely to secure the transition.

In southern and eastern Africa, many observers watched those dynamics with a mix of admiration and frustration.

“We need an ECOWAS in Southern Africa: neighbours who care and insist on the right thing being done on principle,” tweeted Zimbabwean lawyer Fadzayi Mahere, alluding to the failure of southern Africa’s own regional body – the Southern African Development Community – to intervene after an obviously rigged election in her country in 2008.

But as Mr. Grey-Johnson notes, what worked in The Gambia can not simply be sutured onto the political situation of another region.

Southern Africa’s political leaders, for instance, are still largely former liberation fighters “who were together in the trenches and now stand beside one another on their political platform,” he says. “There’s great personal affinity and loyalty that would be very hard to disentangle.”

Zimbabwe's Robert Mugabe may be a despot, in other words, but he is also a comrade.

There are also other reasons why The Gambia may not be the simplest continental model.

The popularity factor

For one thing, Jammeh – a man of manic pronouncements and intense ego who appeared at times to be a creation straight out of dictator central casting – was unpopular in the region, and so had few political allies.

For another, his country is quite literally penned in by Senegal – a banana in the bigger country’s mouth, as many in the region joke. That made regional military intervention, when it became necessary last week, an unusually straightforward prospect.

Still, The Gambia could well become an example for the region going forward in another way, says Amnesty International West Africa researcher Sabrina Mahtani – as a country that rebuilt a commitment to human rights and the rule of law after a long era of political repression.

“But for that to happen, ECOWAS and the international community will have to continue to engage and support The Gambia going forward,” she says. “This struggle is not quite over yet.”