Why your Mexico City taxi driver might be a former executive

Loading...

| Mexico City

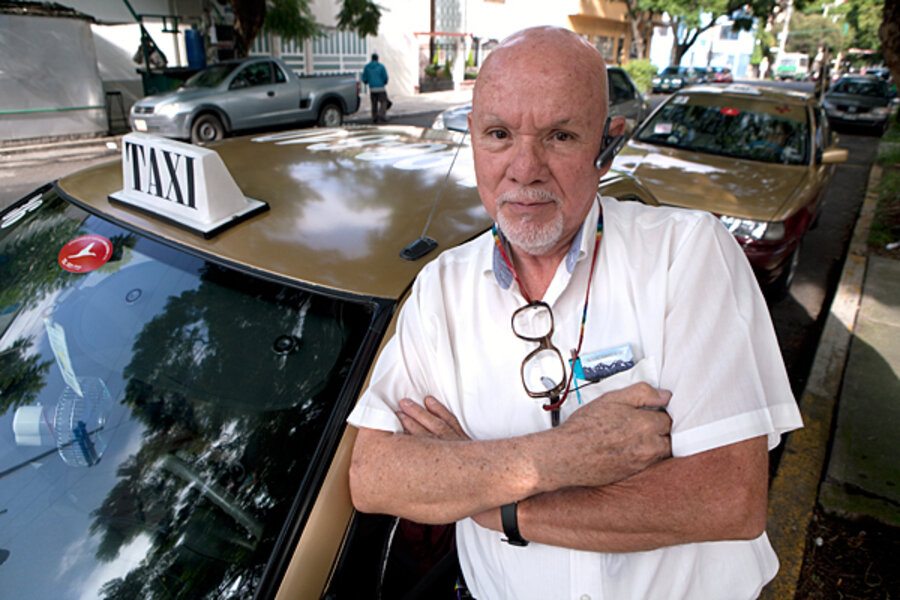

The former Mexico sales chief for Duracell pulls out of his driveway at 6:30 a.m. with a flashing meter, ready for another day on the job. Jorge Antonio Ruiz says it’s absurd to think about his past life as an executive while working his rounds as a taxicab driver.

“How’s that going to help me?” asks the 73-year-old.

Mr. Ruiz’s son, Jorge Antonio, once a newspaper distributor who employed 80 people at his franchise, has also fallen on hard times and has begun driving a taxi like his father.

In cities like New York and Los Angeles, yellow cabs are a stepping stone for immigrants. In Mexico City, taxis can be a last grasp at economic life for experienced professionals who have fallen victim to rampant age discrimination and recent economic crises.

At the city-run taxi training center, the average age of new recruits keeps rising, and close to one-third of the students are now 50 or older, says Emilio Bravo, director of the center.

Gerardo Garfias, a physician who was laid off after two decades in his field, clutches a briefcase with a medical school logo stuffed with taxi documentation for his training course. “I’m embarrassed,” the 53-year-old says. “How can a doctor be a taxista?”

Lack of social safety nets

Throughout Latin America, the lack of a social safety net forces aging workers to remain in the labor force, the vast majority taking menial jobs in the “informal,” or untaxed, sector, says Fabio Bertranou of the International Labor Organization.

The global economic crisis has only exacerbated the problem. Employers are reticent to rehire older workers let go during the recession, forcing more into odd jobs and poverty, says Sandra Huenchuan, at the population division of the UN's Latin America and Caribbean Economic Commission in Chile.

While policymakers and the media focus attention on unemployment among Latin America’s youths, a growing senior labor crisis is largely brushed aside, experts say.

“[Seniors] are still invisible in the public agenda,” says Ms. Huenchuan. Her commission says only 20 to 40 percent of Latin American seniors receive social security, and the problem is likely to worsen as the region’s over-60 population triples to 25 percent by 2050.

In a country where only 25 percent of retirees receive social security – and where unemployment insurance is a new concept with limited reach in few states – former office workers often have no choice but to stay in the workforce.

Age discrimination

Many of them are not even seniors; workers as young as 35 are shut out of interviews by employers seeking younger, cheaper labor, says Ricardo Bucio, president of Mexico’s National Council to Prevent Discrimination (Conapred).

Companies openly flout laws against discrimination by posting age limits in newspaper ads. One listing seeks a podiatrist between 23 and 30 years old. Another requests a female nutritionist: "24-35 years old, proper appearance, thin, responsible.”

Conapred monitors the media’s portrayal of seniors and holds anti-ageism seminars. But deeply rooted beliefs that the elderly are inefficient are difficult to change, Bucio says. Many seniors even believe it’s natural that they suffer discrimination – 41 percent, according to a Conapred survey.

Mexico is making some strides in senior aid, such as expanding its antipoverty Oportunidades program to include the elderly, while Mexico City seniors receive small pensions for food and medicine.

Stress, crime take toll on elderly drivers

Taxi drivers are exposed to high crime rates, as one-third of assaults in Mexico City cabs are perpetrated against the driver, police say. Sixty-eight-year-old Antonio Negrete, once the program coordinator at a state-run television channel and a licensed lawyer, has been robbed more than 20 times in his own cab. He was strangled with a garden hose by one attacker and escaped with his life thanks to a passing police patrol car.

Ruiz, the former Duracell sales chief, says he wards off dangerous passengers with a Virgin of Guadalupe photo pinned to his sun visor and a religious figurine glued to his steering wheel. He worries about the stress produced by the long hours in Mexico City's chaotic traffic, which takes a toll especially on older taxistas.

And for some who had reached the height of their profession, taxis can be a demeaning alternative. Dr. Garfias says he'll spend a year driving a cab and then get back to his patients fulltime. He’s just waiting for the crisis to blow over.

Mr. Negrete had thought the same thing when he became a taxista two decades ago.