Mexico activists vow to press ahead after mother seeking justice is murdered

Loading...

| Mexico City

All she wanted was justice for her slain daughter.

But what Marisela Escobedo Ortiz received was a bullet in the head, after leading a series of marches, including most recently a sit-in outside the governor’s palace in Chihuahua City in northern Mexico, demanding that the killer of her teen daughter face sentencing. It was there, last Thursday night, that masked men drove up to the government hall and shot Ms. Escobedo dead.

Her daughter’s death, her own death last week, and then the killing of a brother-in-law on Saturday has shocked Mexico, where even hardened residents wonder at the limits of impunity these days. Many activists say they believe the message was clear: to stifle the voices of those who dare fight the status quo.

Much violence here, with all of its various roots and expressions, has had a silencing effect. Journalists intimidated by drug traffickers have erased their bylines or refused to cover organized crime. Citizens, fearful of corrupt police, do not report crimes. Business owners, avoiding extortion or worse, have shuttered their doors.

The plight of the Escobedo family will not turn that trend around, say social activists in Chihuahua state.

“The way in which she was assassinated, and everything surrounding the case, leaves a clear message for the community of social activists and human rights workers that we should be quiet,” says activist Marisela Ortiz of Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa, a group fighting against the disappearance of women in Ciudad Juárez in Chihuahua state. “But for those of us who are dedicated, the murder is pushing us to unite and continue this fight.”

Escobedo’s daughter, Rubi Frayre Escobedo, went missing in 2008 at age 16 and was found in a trash bin in 2009 in Ciudad Juárez, across from El Paso, Texas, burned and dismembered.

The main suspect was her boyfriend Sergio Barraza, who prosecutors have said confessed to the murder and led authorities to the body. But at his trial in April he was let go for a lack of evidence. Photographs from that day showed Escobedo collapsing in a heap of despair, but she found her fortitude and began staging marches and demanding justice.

Most recently she had gone to the governor’s palace for three days and promised not to move until the investigation made progress. A security camera filmed a car pulling up to the building last Thursday night. In the video already viewed more than 1 million times on YouTube, Escobedo tries to flee but a gunman chases her across the road and shoots her in the head.

Mexican President Felipe Calderón condemned the killing of Escobedo on his Twitter account over the weekend. “Such impunity caused the murder of Marisela Escobedo,” he wrote.

The three judges in the case have been suspended. A spokesman for the state attorney general’s office told the Associated Press that Mr. Barraza now is also a suspect in Escobedo’s homicide. Two days after she was shot, the asphyxiated body of Escobedo’s partner’s brother was found, after his lumber store was torched.

It is unclear if the deaths are related, but the family plight highlights the chaos that has befallen parts of Mexico. In Ciudad Juárez, the nation’s most violent city, more than 3,000 people have been killed this year alone. Drug violence, as the Sinaloa cartel battles the Juárez group for turf control, has been the culprit. In the 1990s, the city was made notorious for the random murders of women known as “femicides.”

Hugo Almada, a long-time activist in Juárez who participates in a government program to bring safety to Juárez, says that all sectors have been affected by the violence that has spiked since 2008. “The people already were scared for their lives, this is not new,” he says.

Escobedo is not the first social activist to be killed. Across the country, throughout the decades, human rights defenders and activists, whether environmental or social, have been assaulted and intimidated and sometimes killed. Ms. Ortiz says, however, that in the midst of the current drug violence, which has caused more than 30,000 murders in four years, activists feel more exposed.

“In this climate of violence, when anyone can be killed, and we do not know where it is coming from, we are even more vulnerable,” says Ortiz. “The incapacity of the state, the impunity, the chaos in which we are living makes us more vulnerable every day.”

“Yet again, it was impunity that led to these homicides,” says Jose Antonio Ortega, the president of the Citizen’s Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice in Mexico City. “I only hope it leads to more people raising their voices.”

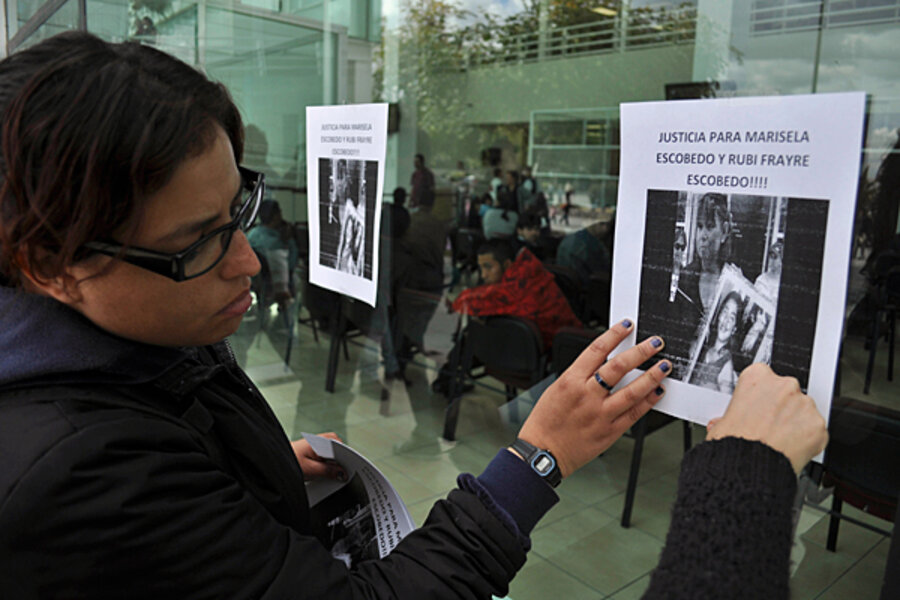

Ortiz says it will. On Friday, after Escobedo’s murder, activists gathered outside the state prosecutor’s office holding signs reading “Justice for Marisela.” Many more protests are planned.