Spread of drone programs in Latin America sparks calls for code of conduct

Loading...

| Mexico City and Rio de Janeiro

In December, a UFO landed near Reyna Hinojos's house on Craddock Avenue, in an El Paso, Texas, neighborhood separated from Mexico by the Rio Grande. Her startled neighbors dragged the aircraft into their front yard and called the police, who identified the object: an Israeli-built unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) operated by the Mexican government to monitor drug trafficking and human smuggling.

The small drone had landed safely, says Ramiro Cordero, an agent with US Customs and Border Protection. It was promptly loaded into a police pickup truck and returned to Mexican authorities.

Ms. Hinojos was unsurprised by the incident, since her border town constantly swarms with surveillance vehicles such as helicopters – one of which crashed a few years ago.

"They might have their dangers," she says of drones, "but I feel safer knowing they're out there."

RELATED: The world in 2011: Trends and events to watch in every region

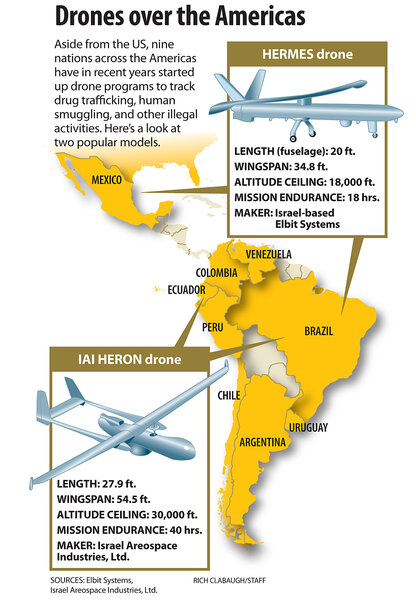

Countries throughout the Americas are deploying drones as a high-tech answer to tackling drugs, gang violence, and activities such as illegal logging. From Canada to Brazil, at least 11 nations are flying UAVs over the Western Hemisphere, often Israeli-made. Brazil's Army in January purchased its first two Hermes drones, and its federal police force is set to deploy its first surveillance UAV by July.

Code of conduct needed

Drones are here to stay, experts say, and the time is past for debate. At this point in the game, Latin America should collaborate to develop a code of conduct that will prevent the arming of drones and assuage civilian concerns, says Johanna Mendelson Forman, a Latin America specialist at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, in Washington.

"I think it's the maturation of Latin American defense systems," she says, while cautioning that the potential to arm drones could turn the project into a "double-edged sword."

Latin American politicians are also raising calls for an international pact that defines the scope of drone missions. "Regulations should be established," says Mexican Sen. Fernando Baeza, who advocates a limit on data collection. "The great precision of satellite information could be put to good use, or could be used for spying."

Drones are an invaluable resource to aid investigators on the ground, analysts say. They can jam signals, locate enemy satellite dishes, spot drug plantations or cartel hideouts, and monitor a country's own police force for corruption, says Inigo Guevara, a Latin America security researcher with Georgetown University.

"You still need people on the ground to intercept, to interdict, to make arrests, to get involved in firefights," Mr. Guevara says. "But you can protect them a lot more if you have your eye in the sky."

Israeli companies eye clients

Make that plural: eyes. Washington in August began patrolling the entire US-Mexican border with Predator drones, and several US counties reportedly have pilot programs in police and sheriff offices. The US also sends high-altitude drones over Mexico that "have been particularly useful in achieving various objectives of combating crime," the Mexican National Security Council said in a statement March 16, days after the controversial program was exposed by The New York Times. (The Associated Press later reported that the US has flown Predators into Mexico since 2009.)

Mexico in 2008 deployed its own drones to crime-plagued Ciudad Juárez (across the border from El Paso) and today operates up to 30 UAVs nationwide, says Guevara. Programs also exist in Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. None are armed and most are discreet. Hugo Chávez in 2009 accused Colombia of sending drones to capture images of Venezuela, which Colombian officials dismissed as "Santa's sleigh."

Israel Aerospace Industries has sold its Heron to Mexico and Ecuador, where it has a branch in addition to offices in Brazil, Colombia, and Chile. Another Israeli firm, Elbit Systems Ltd., has sold its Hermes to Mexico and Brazil. The company's Brazilian subsidiary, AEL Sistemas, citing the "great strategic relevance" of the drone market in Latin America, declined to speak with the Monitor. In April, Elbit signed a "strategic agreement" with Brazilian aircraft manufacturer Embraer, which lauded drones' "dual-use for monitoring of ports, agricultural, forest, and coastal areas, traffic, etc."

Brazil puts 'eyes in sky'

Brazil's president has openly advocated drone use. "This allows us to perceive transporting of arms, drugs, and suspect movements," Dilma Rousseff said while campaigning in August. Drones also enable police "to see the movements in the regions with the greatest commercialization and distribution of drugs."

In addition to dispatching the Heron to Brazil's porous western frontier – the 10,500-mile border touches 10 nations – police are also considering flying drones over violent cities and the Amazon, to fight deforestation and illegal exploitation of natural resources, according to a police spokesman, adding that 14 Heron drones are to be purchased by 2014 for $395 million. Adriano Kancelkis of São Paulo-based AGX Tecnologia, the first Brazilian manufacturer to produce UAVs, says he expects strong demand from the agricultural industry and environmental lobby.

Brazil is now negotiating a code of conduct with Colombia, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay to allow an incoming fleet of federal police drones to monitor their territories – under the promise that each government could view the data and flights would be limited.

Vanda Felbab-Brown, a Mexico expert at the Brookings Institution in Washington, cautions that drones should not replace traditional policing methods. "Although [the UAV] is another tool and probably facilitates following particular individuals," she says, "I don't think it has the potential at all to bring any crippling blow to any particular organization."

RELATED: The world in 2011: Trends and events to watch in every region