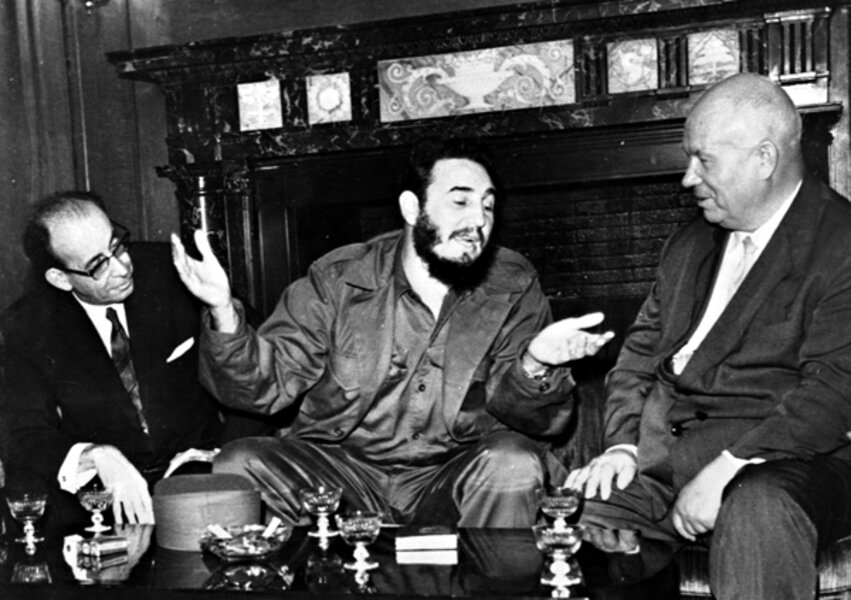

Cuba is the only Communist country in Latin America, and its move to a one-party system after the Cuban Revolution in 1959 set the stage for hostile US relations that endure today. While the Communist Party of Cuba had been active in the island nation since the 1920s, the current party makeup was organized by Fidel Castro in 1965. The system has persisted despite 50 years of embargo put in place by the US. Cuba was buoyed by the Soviet Union until its demise in 1991, underwent severe economic hardship through the '90s, and today receives support from Venezuela. While other political parties exist in Cuba, it remains a one-party system with elections that are considered a rubber stamp.

Fidel Castro headed the nation for half a century, until permanently ceding power to his brother in 2008 due to illness (he was head of the Communist Party until April 2011). Raul Castro, considered the more pragmatic of the two brothers, has implemented a series of economic reforms since taking power to revive the ailing economy, including allowing more Cubans to start their own businesses. But while Cubans and Cuba observers have hailed this economic opening, there has been no sign that political freedom will follow.