'We are millions': Victims of organized crime in Mexico seek justice in new law

Loading...

| Mexico City

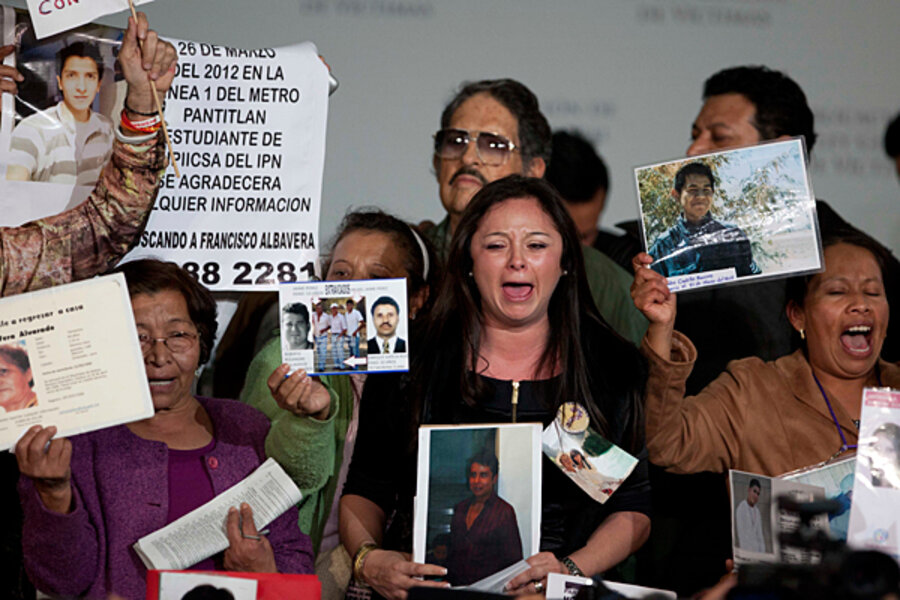

Rocío Uribe Ruiz stood at the back of a conference room in the Mexican presidential residence, silently holding a picture of her missing daughter, as President Enrique Peña Nieto touted a new law to protect victims of the country's devastating organized crime epidemic.

With more than 60,000 people killed in drug violence in the past six years, and tens of thousands more disappeared, Mexico now faces the monumental task of addressing the needs of the growing group of those affected. The new legislation, signed into law this week, promises to do just that. For the first time, Mexico will specifically address victims' rights with additional legal protection and financial reparations, among other benefits.

Dozens of relatives whose loved ones have disappeared without a trace — and whose cases have gone nowhere in a country where fewer than 4 percent of crimes are ever solved — squeezed into the packed Los Pinos hall as Mr. Peña Nieto announced that with the law, only the second of its kind in Latin America, “the Mexican state aspires to return hope and comfort to victims and their families.”

“It gives me hope,” says Ms. Uribe Ruiz, whose 14-year-old daughter, Maria Fernanda Tlapanco Uribe, went missing nine months ago. “But really, will it be applicable to us, and not just to whoever they want? The laws aren’t for us. They are for the ‘big’ people.”

The law, officially called the General Law of Victims, is the joint work of academics, advocates, and victims themselves. Proposed and promoted by the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity – which is led by the poet Javier Sicilia, whose son, Juan Francisco, was killed in March 2011 – the law received nearly unanimous support in Congress last year before hitting a wall with former President Felipe Calderón.

Mr. Calderón declared the law unviable and unconstitutional. However, Mr. Peña Nieto promised to revive it.

To start, the law makes “victim” a legally recognized entity. It provides for a victim’s right to respectful treatment, a full investigation of the crime, and the awarding of damages whenever possible.

The law also demands the creation of a new National System of Attention to Victims to aid victims in various capacities, a national victims’ registry, and a fund to dole out reparations – ostensibly to be paid for with cash and property seized from criminals.

Critics, including other victims' groups, say the law is flawed. In a statement, the victims’ advocate group Mexico S.O.S. highlighted what it sees as the law’s failings. For one thing, the group says, it only covers victims of federal crimes, not state and local crimes. And it creates a scheme in which the state must pay out damages caused by a criminal. What's more, they argue that the law defines “victim” in terms that are unnecessarily sweeping and vague.

Peña Nieto conceded the law “still needs to be improved” and has asked lawmakers to work up reforms.

Colombia was the first nation in Latin America to enact legislation protecting victims. That country's June 2011 Victims and Land Restitution Law sought to restore millions of acres to people displaced by the decades of fighting between the government and guerrilla forces. The law also provides for financial compensation to victims of human rights violations.

It would have been better if Mexico’s victims’ law wasn't necessary, Mr. Sicilia said during the ceremony. “It’s the consequence of not applying the laws that are made to protect and provide justice to citizens. It’s the consequence of impunity, corruption … and of a war that never should have been.”

“I have hopes that they’ll listen to us,” says María Eugenia Morales, whose 19-year-old daughter, Nayeli Francia Morales, has been missing for nearly two years.

“We aren’t just one or two” who have lost someone, she says. “We are millions.”