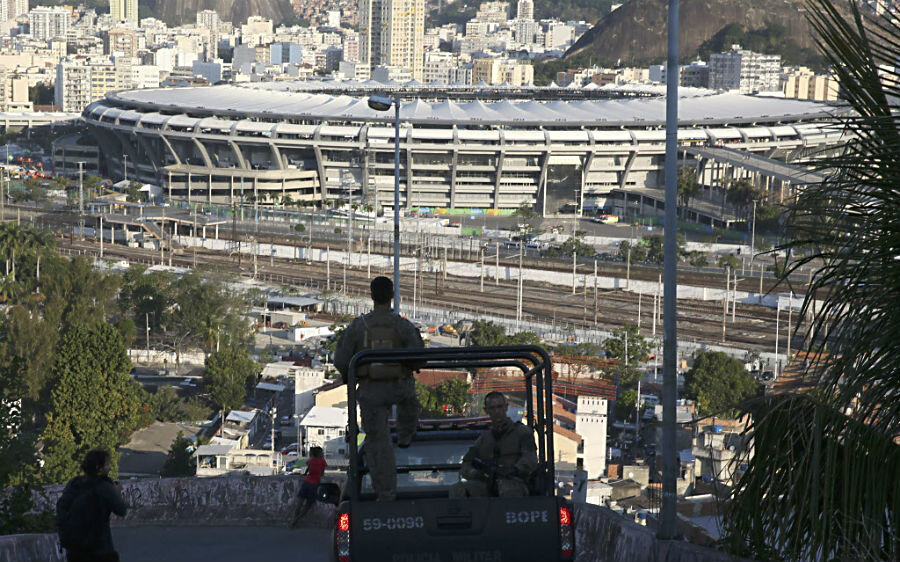

From Rio's hillside slums, Olympic Games viewed as missed opportunity

| RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil

For decades, Rio has been viewed globally as an urban paradise, nestled between famous beaches like Ipanema and Copacabana, and dramatic, rain-forested mountains.

But its natural beauty is juxtaposed with extreme economic segregation. While the wealthy walk the streets that appear on the post cards and in films seen around the world, impoverished favelas sprawl across Rio’s hills, historically disconnected from the formal city.

It’s a contrast civil servants and activists have long said they’d like to resolve, from “favela upgrading” plans in the 1960s to more recent promises to better integrate the city and even out disparities via Olympic Games’ infrastructure projects.

Between a fifth and a quarter of the city’s six million inhabitants live in favelas, an estimate that excludes the wider Rio conurbation. The hope was that the billions of dollars of Olympics investment would effect change for a swath of the city’s poor, who say they’re too often overlooked, ignored, or — worse — hidden from view when Rio hosts lavish global events.

Today, as tourists walk along Copacabana, passing a blue marquee selling Olympic apparel and giant sand sculptures welcoming them to the city, there’s “another city, a hidden city,” says Leonardo Soares dos Santos, a historian at Fluminense Federal University.

Pledges to make up for past planning mistakes, like a program that envisioned a sweeping overhaul of the favelas — essentially formalizing them by 2020 — fell short. And as the Games kick off this weekend, many here question whether Rio missed its best opportunity in more than a century to truly live up to its nickname, “The Marvelous City.”

“The [Olympic Games] investment has exacerbated inequality,” says Mr. Soares dos Santos, referring to the $12 billion spent on the Games, according to the last official figures. The final price tag is predicted to be much higher.

“It has not been distributed evenly, which is Rio’s historic problem.”

'The exclusion Games'?

In 2010, Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes announced a project called “Carioca Living” (as residents here are known) packaged as a centerpiece of the 2016 Olympic Games’ “legacy” upgrades. The plan — which included provisions for better sewage, paving roads, and constructing plazas and social service centers — aimed to seek out universal, long-term benefits for hosting the Games.

“It was beautifully written,” says Theresa Williamson, the director of Catalytic Communities, an organization that advocates for the formalization of favelas.

The favelas have been around for generations, establishing their own methods for grappling with the problems of living precariously on hillsides, like motorbike taxi services that whizz up the slopes. Such innovation, however, cannot address all of the issues: Constructing ad hoc drainage systems to channel stormwater runoff, for instance, is not enough to guarantee that homes are not at risk of falling away with landslides.

But just as architects started gushing about how Carioca Living could be used as a tool for breaking down the socio-economic divide here, the ambitious project started to unravel. In some neighborhoods, construction halted; in others, critics say, plans for a bottom-up, democratic planning processes meant to best meet the needs of favela residents were ditched in favor of quicker, top-down decisionmaking.

“These are the exclusion Games,” says Cosme Vinícius Felippsen, a sweets seller and tour guide in Morro da Providência, Rio’s oldest favela, which was settled in 1897 by veterans of a civil war. Providência overlooks Rio’s port, an area that was renovated for the Olympics, including the inauguration in 2014 of a cable car meant to ease the climb into the cliff-side neighborhood.

With the favelas already reeling from police brutality, a once lauded pacification program, and “remoçoes,” or forced evictions — often to make way for Olympics-related infrastructure — the homes of hundreds of families in Providência were marked under upgrade plans for demolition in 2011. These planned tear-downs were halted only after the community initiated legal proceedings against the city through the public defender’s office.

Meanwhile the cable car, according to Mr. Felippsen, was not a pressing need. “We wanted schools and basic sanitation,” he says, the smell of prawn gnochhi from a nearby kitchen and hip-hop music wafting in the air.

Tracing Rio's history

The history of Rio’s development is, in many ways, tied to the history of its policy toward the favelas.

In the years after Brazil won independence from Portugal in 1889, Rio – then the capital – expanded. Urban planners reclaimed marshland and revamped infrastructure, following the blueprint of Georges-Eugène Haussmann, a public official who redesigned Paris in the 19th century. These upgrades, however, involved bulldozing tenements where poor rural migrants lived, pushing them into what are today favelas.

During the 1930s, Rio drafted a policy specifically addressing the favelas, fueling expectations, Soares dos Santos says. Many hoped their problems — which mirror those in shantytowns across the region, like poor sanitation and crime — might be resolved. But too often, the policies were based on attitudes of exclusion, experts say, with residents in the 1940s, for instance, simply resettled in isolated ghettos called “proletarian parks.”

From the 1960s onward, however, projects emerged that emphasized greater participation of residents in favelas, most notably one that began in the 1990s under former Mayor Cesar Maia, called Favela-Neighborhood. It was considered a leap in progress, not only in terms of significant improvements to infrastructure, like concrete staircases, but for how increased formalization promised to help reduce discrimination against these communities.

'Marvelous for me'

Still, few favela residents – many of whom are part of families that have lived there for decades – feel city leaders have created many noticeable changes.

High in the neighborhood of Babilônia, far above the recently gentrified sections closer to the formal city, Maria Regina Luiz’s home sits in the shade of tropical trees. Although she has spectacular views of Copacabana Beach and the Atlantic Ocean, her home is built of rotting wood and corrugated iron on a precarious mud slope.

“It’s the same as it always was,” says Ms. Luiz, whose neighbor has a dream-catcher pinned to the front door. “Nobody leaves here and nobody takes us out.”

Critics here have unleashed attacks on Mayor Paes, alleging that his approach to Olympic planning has accentuated the rich-poor divide. For example, some residents point to how he let Carioca Living slide by but invested heavily in Barra da Tijuca, the already wealthy neighborhood where the Olympic Village is situated.

While Brazil’s economic downturn in 2014 recently led interim President Michel Temer to commit to reducing government spending, activists like Ms. Williamson claim Carioca Living was sidelined around Jan. 2013, after Paes won reelection, because of the political influence of powerful interest groups who resist integrating the city.

Carlos Vainer, a professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s urban planning institute, says policymakers preparing for the Games have disregarded the idea of cities – and Rio – as shared “spaces of encounter.”

“When you separate the spaces,” Mr. Vainer says, “you kill the soul of the city.”

Paes denies accusations of prioritizing the rich, telling the Guardian last month that “there has never been so much transformation for poor people” in Rio, and claiming that new bus lines will benefit residents on the city’s north, poor side.

While many residents of the favelas fervently disagree with Paes, some are optimistic about the future.

In Babilônia, João Medeiros da Silva, a retired firefighter, lives in a modern apartment block with two of his daughters. The building was constructed with funds from Carioca Living, completed around 2012. Mr. Medeiros da Silva says it was wrenching when he had to move out of the favela home he had built himself into this new apartment, which residents say was poorly built.

But he is upbeat about the long-term impact of the Olympics. Tracing a history of his life here in Rio, he says that, all in all, things haven’t been too bad.

“Up until now,” he says, “it has been marvelous for me.”