Britain names Chagos Islands world's largest marine preserve

Loading...

A patch of ocean roughly the size of Texas and harboring some of the world's most pristine coral reefs has received tough new protection from the British government.

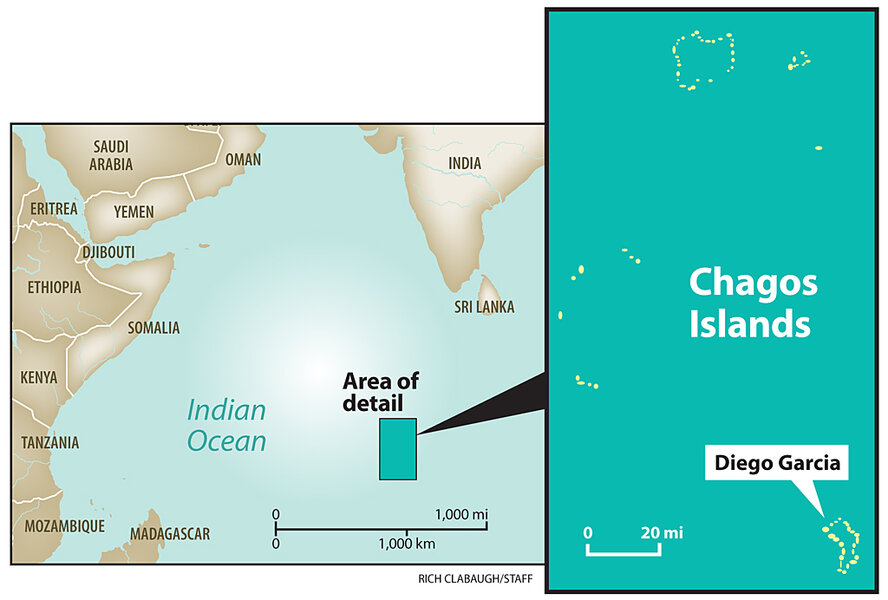

The 210,000 square-mile area, which embraces the Indian Ocean's Chagos Island archipelago, now represents the world's single largest marine protected area trumping the previous record marine-conservation set-asides. President George W. Bush approved the establishment of national marine monuments around the northern Hawaiian Islands in 2006 and along the Marianas Islands in 2009.

Taken together, the areas Britain and the US have designated for protection represent nearly half a million square miles of unique ocean ecosystems that serve as nurseries for a broad range of marine life.

Britain's declaration "is a historic victory for marine conservation," says Jay Nelson, director of the Pew Environment Group's Global Ocean Legacy project. Part of the area will be a "no take" reserve, meaning no fishing or collecting of living things at all, while human activities will be strictly regulated in the rest of the larger protected area.

These moves, along with the Coral Triangle initiative in the tropical western Pacific, highlight the increasing emphasis scientists, conservationists, and governments are placing on trying to protect ocean ecosystems critical to the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people as well as to the biological diversity of the oceans themselves.

According to a global survey of reef health published in 2008 by the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, in the next 10 to 20 years, 15 percent of the reefs existing today will be threatened by stresses such as pollution and destructive fishing practices. That number is expected to grow to 20 percent in the next 20 to 40 years as the number of people living on coastlines in reef-rich regions increases.

The study also indicates that some 48 percent of the reefs are in relatively good shape. But they and the rest of the world's reefs face additional threats from global warming and ocean acidification, the study cautions.

The designation, three years in the making, has seen some small-scale opposition. Roughly 4,000 people lived in the archipelago, a British territory, until London moved them in the 1970s to make way for a joint US-British military base on Diego Garcia, the largest island. Since then, the island also has become one of several emergency landing sites for NASA's space shuttles.

The islanders, who have long insisted that they be allowed to return to the islands, were the most vocal critics of the new marine protected area. They have been battling the British government since their forced removal for permission to return to the islands. They argued that the designation was little more than a ruse to keep islanders from returning.

Still, the move to tighten environmental protections for the archipelago and its reefs has drawn wide international support.

'Best hope'

The new protected area "is one of last best hopes for the Indian Ocean," says Charles Sheppard, a marine biologist at the University of Warwick in Britain who has spent the past 30 years studying reefs in the region, including the reefs in the Chagos Islands.

Along Indian Ocean coastline, many of the reefs people rely on to support fishing are in bad shape, he explains. By contrast, the archipelago, some 1,000 miles south of India, is largely uninhabited.

Free of human pressures, the archipelago's unpolluted water is far clearer than waters around coastal reefs, allowing corals to grow at deeper depths. This allowed them to survive a severe, heat-related coral-bleaching event in 1998. They then served as the reservoir for larvae that replaced the dead corals at shallower depths. Reefs in the archipelago "bounced right back," Dr. Sheppard says, while many reefs in the broader Indian Ocean region have yet to recover.

This not only illustrates the benefits of reducing human stresses on reefs, but the archipelago's reef network in principle could provide the biological building blocks to restore reefs and sustain fisheries elsewhere in the region, researchers say.