Japan sinks (even) lower on gender discrimination report

Loading...

| Tokyo

Chie, a former saleswoman at a Japanese firm, remembers paying her dues at the office. She put up with men who slapped women’s backsides. She donned a uniform and showed up the required 15 minutes early to brew coffee. Finally, after five years, she told her boss she wanted to take over from two departing salesmen.

“At the next meeting, he said he was hiring two guys for the jobs,” recalls Chie, who did not want to use her full name. “I quit. And then my boss asked me, ‘Oh, were you serious?’

“I was the first and last person to take maternity leave at that company,” she adds.

Japanese companies have long had a reputation of being unfriendly to women, especially mothers. That image was reinforced recently by the World Economic Forum, which downgraded Japan in its Gender Gap Report from 98th of 130 countries in 2008 to 101st out of 134 countries in 2009.

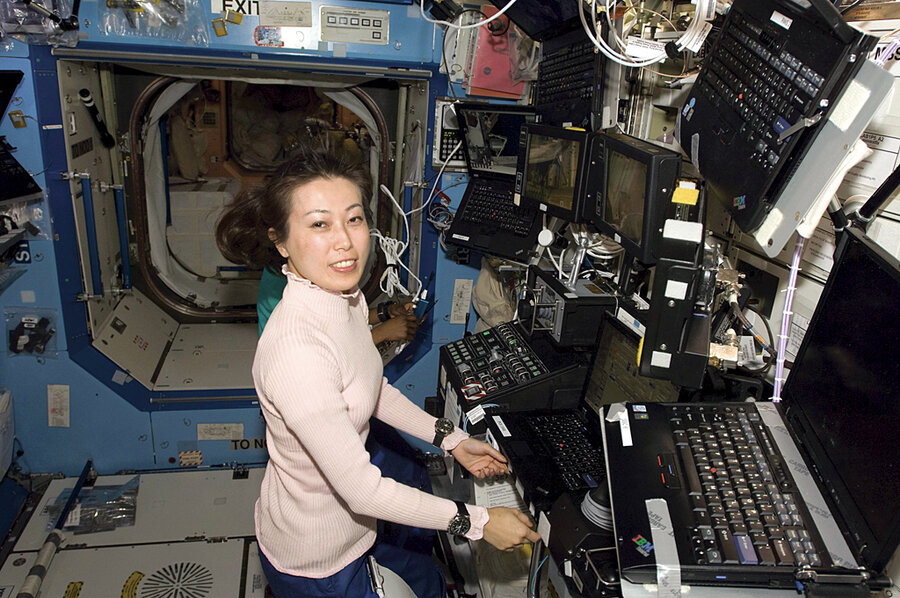

But on April 19, government and industry representatives set a target of getting 55 percent of women to return to work after having children. Also in April, Japan celebrated Exhibit A for that goal: “mama astronaut” Naoko Yamazaki, who was part of a recent space shuttle crew. And Japan’s low birthrate, and the falling ratio of workers to the aging, are prompting more companies to try to appeal to women.

IN PICTURES: Top 10 developed countries where women make less than men

IN PICTURES: Top 10 developed countries where women's pay comes closest to men's pay

“Since the population started falling, and then the financial crisis, companies are more conscious of hanging onto their best workers, including the most talented women,” says Miko Fukushima, a mother of two who returned to work at a multinational finance-related firm.

“At some of the biggest Japanese companies, benefits for women, such as maternity leave and creche facilities, are better than at many foreign firms,” she says. “Most of the smaller firms, even some bigger ones, have a long way to go, though.”

Government figures show the situation has actually deteriorated since the first legislation on workplace discrimination in 1985. Some firms categorized employees as “career” or “administration,” with women invariably herded into the latter category. These “office ladies” typically did routine clerical work and served tea.

Between 1985 and 2008, the proportion of female full-time employees fell from 68.1 percent to 46.5 percent. Put another way, 53.5 percent of women in the workforce are part-time or contract workers, while the figure for men is 19.1 percent.

In 2007, a strengthened law passed that outlawed such indirect discrimination. But successful legal challenges to the status quo remain few.

As a result, ambitious young Japanese women often head to foreign firms. “I worked as a temp at Dell in Japan and was really surprised: There were women managers and women in other senior positions,” Chie says. With her heart set on working for a firm that would take her seriously, she went to the United States to get a law degree, and was later hired to work in the legal department at Dell in Japan.

Still, the recent response to Ms. Yamazaki, the astronaut, may inspire some young girls. Yamazaki, who has a young child, joined another Japanese national on the International Space Station in April. The media ran numerous stories of how her husband, who also worked in the space program, put his career on hold for her, and the stress it had put on their family.

“I think she’s very impressive and makes me think Japanese women can do anything,” says Yuki Saito, a student at a women’s university in Tokyo. “Women of my mother’s generation had fewer chances for a career, let alone a career and a family,” she adds. “While the situation for us is still very different [from those of] women in foreign countries, it is getting better.”

IN PICTURES: Top 10 developed countries where women make less than men

IN PICTURES: Top 10 developed countries where women's pay comes closest to men's pay

Related: