Facebook provides community for Indonesia's street kids

| Malang, Indonesia

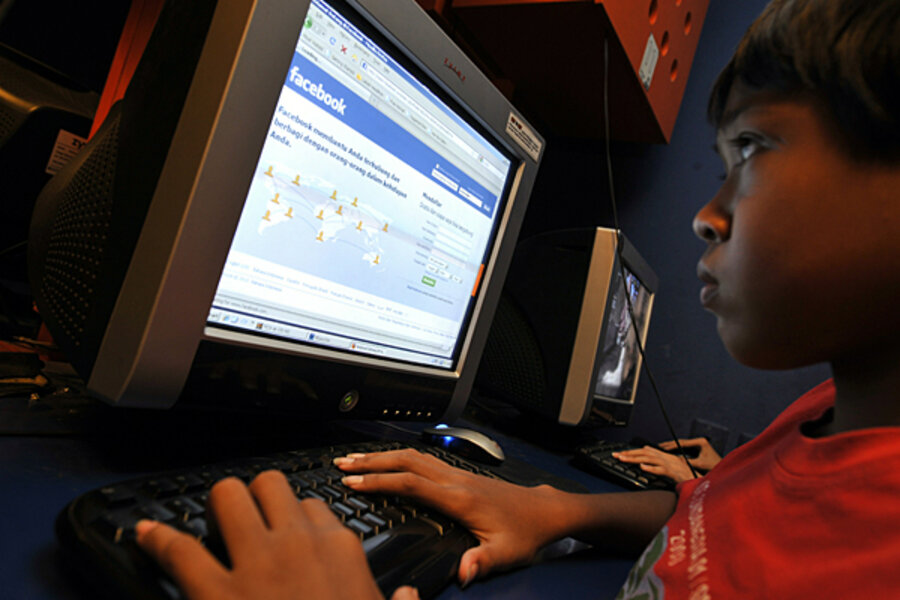

The night can be tough for Indonesia's street children. Competition between gangs can turn bloody, and sexual abuse is common. Rather than sleep under bridges or fend off predators, many are finding relief in Facebook.

The hours between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m. are strangely busy at Indonesia's Internet cafes, where special packages allow kids to spend evenings online with a cup of coffee or piece of bread, all for only $1.

The intent is to entice users during off hours, says Azza Azzahra, an employee at Greenjaya Internet, where many of his late-night customers are teenage boys.

The kids at East Java Humanitarian Network, or JKJT, a nongovernmental organization educating street youths, say it helps street kids feel normal.

Richard Anderson, a homeless 16-year-old from East Timor, says he uses Facebook to practice English with friends from Australia and Hong Kong. "I ask how things are in their country, like how is the weather," he says. Like young people around the world, the boys update their statuses and flirt with girls. When they're not on Facebook they download music or watch movies – "Twilight," "Eclipse," and "Avatar" are favorites.

Adi Danando is a child-labor activist who has been working with and researching street children for more than three decades. Kids living on the street 24 hours a day are under a lot of pressure, he says. They are excluded and judged, which leads to identity problems. Many don't have birth certificates, which are required to enroll in school, so on paper they don't actually exist.

"Facebook provides these kids with a sort of identity, which gives them a sense of pride and belonging," Mr. Danando says.

The social-networking site also allows them to communicate with people from different backgrounds. And games can teach them business skills like negotiating and idea sharing.

Around 15 percent of Indonesia's 150,000 street children have no connection with their families or any residential status, denying them access to school and health services, according to government figures.

"For them, Facebook can be useful because it can help them develop relationships with other people," says Tata Sudrajat, a child protection advocacy and research adviser for Save the Children.

It appears that is just what's happening. Dendys, a homeless teen who goes by only one name, counts an Australian volunteer who taught him English on Facebook as "family." Richard includes other street kids.

Unless they have access to nonprofits or health workers who will listen to them, Mr. Sudrajat says, they have no one to talk to about their problems and start the healing process. The Internet and Facebook begin that for these kids.

But Sudrajat is quick to point out that midnight Web-surfing isn't a permanent fix and comes with its own set of dangers. Internet pornography and a lack of monitoring can be a dangerous combo. In February, police arrested two men for running an underage child prostitution ring that used Facebook to find recruits.

Still, Richard says the benefits outweigh the negatives. Internet cafes have security cameras to monitor customer activities, and even if they didn't, he says he's not interested in spending his money on smut.

"At this age, kids like Facebook and games," agrees Irva Reza Mugroho, a teaching volunteer at JKJT.

Until access to rehabilitation centers becomes available to help these youths overcome traumas and teach them to communicate with others in person, Danando says he and other NGOs will continue to use Facebook to connect with them and offer advice in the wee hours. "Those kids that are on the streets 24 hours a day have many problems. They are confused and ridiculed. But no one judges them on Facebook."