The economic road ahead for China and Pakistan

| Aliabad, Pakistan

Until last year, shopkeeper Sher Afzal sold Lay's potato chips and baked goods to Western backpackers visiting this idyllic Himalayan valley. Now that rising terrorism has squelched tourism and China's economic boom has brought development, he is selling Chinese instant noodles and packets of dried meat to a very different clientele.

"With the state of affairs, there's more business with the Chinese now," he says of the interest that China, the world's second-largest economy, now takes in Pakistan.

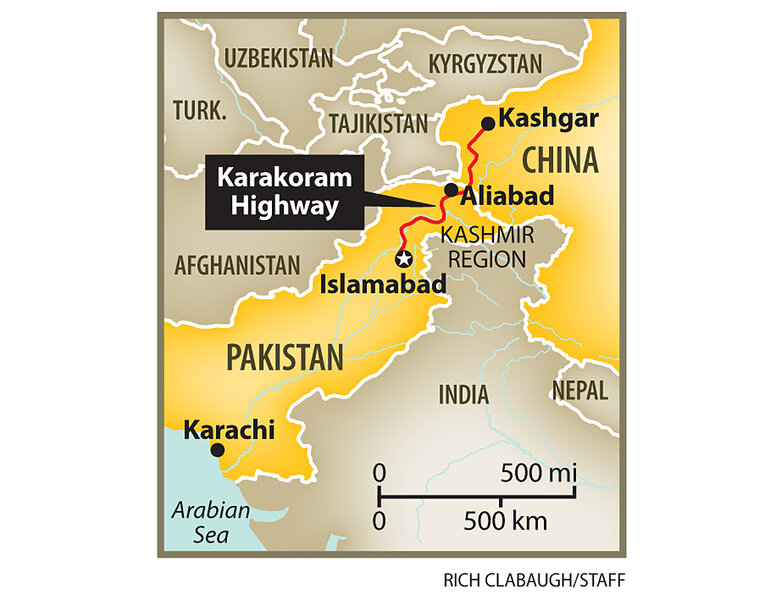

In the past four years, thousands of Chinese workers have descended on the Hunza Valley for an ambitious repair project on the legendary Karakoram Highway. An epic feat of engineering, the 800-mile, two-lane ribbon that wraps its way in hair-raising curves through passes as high as 15,000 feet connects western China to Islamabad, Pakistan, and thence to roads leading to the deepwater port at Gwadar.

The relationship is not new: The road was first built between 1959 and 1979 by the People's Liberation Army. But while Pakistan's relations with the West, particularly the United States, remain difficult, the highway – along with other major Chinese-built projects such as the port at Gwadar and Pakistan's main nuclear reactor at Chashma – is a symbol of the road ahead.

"It's part of a larger, overall infrastructure project, which is geared toward enhancing connectivity with Gwadar and the western regions of China," says Fazal Ur Rehman, director of the China Studies Center at the Institute for Strategic Studies in Islamabad.

Out where the highway bends between Gilgit and the Khunjrab border pass, gangs of workers hack at mountain walls with pickaxes and are watched over by a Pakistani security division created just for the Chinese workers. The $400 million upgrade and expansion project is expected to be completed by early 2013.

The Chinese have made themselves popular here, largely because of the highway they built, which transformed the Hunza Valley 30 years ago, and the diligence with which they are now upgrading and expanding it.

After recent floods, says Abdullah Jan, local head of the roads department, "our experts said they needed a month to complete the [repair] work." Working day and night, the Chinese finished in 10 days.

Life is tough for the Chinese surveyors, engineers, and laborers – all employees of the state-owned China Road and Bridge Corporation – who are working on the project, says manager Pong Chenhai. The views may be stunning, but they work from dawn to dusk seven days a week for as long as a year at a time, with only one week's home leave. A typical engineer earns $700 a month, about 30 percent more than what an engineer makes in China.

They live in temporary camps or in local guesthouses specially equipped with Chinese kitchens and chefs.

"The Chinese are good for business, but they mainly keep to themselves," says Abdul Qayyum, manager of the Hunza View Hotel. "They don't talk to the other guests, and the guests don't talk to them, mainly because of the language problem. They mainly stay in their rooms."

Bringing money and assistance, though, the Chinese are welcome here in a way the Chinese authorities hope similar work crews will be welcome across Africa and Asia, as Beijing spreads its development aid largess. China's image here as an all-weather friend, says Mr. Rehman, "should definitely have an impact on China's relations with other nations in the developing world."