China gives cool response to US military activity in Australia

| Beijing

As Washington and Beijing spar this week in a new round of their heavyweight contest for influence in Southeast Asia, the Chinese have diplomatically ducked a number of American punches. But the resumption of hostilities has alarmed local analysts here.

“They are sending a clear cut message to China, that America is back and wants to hold down or roll back China,” says Zhu Feng, a professor at Peking University’s School of International Studies. “This will not facilitate diplomatic cooperation.”

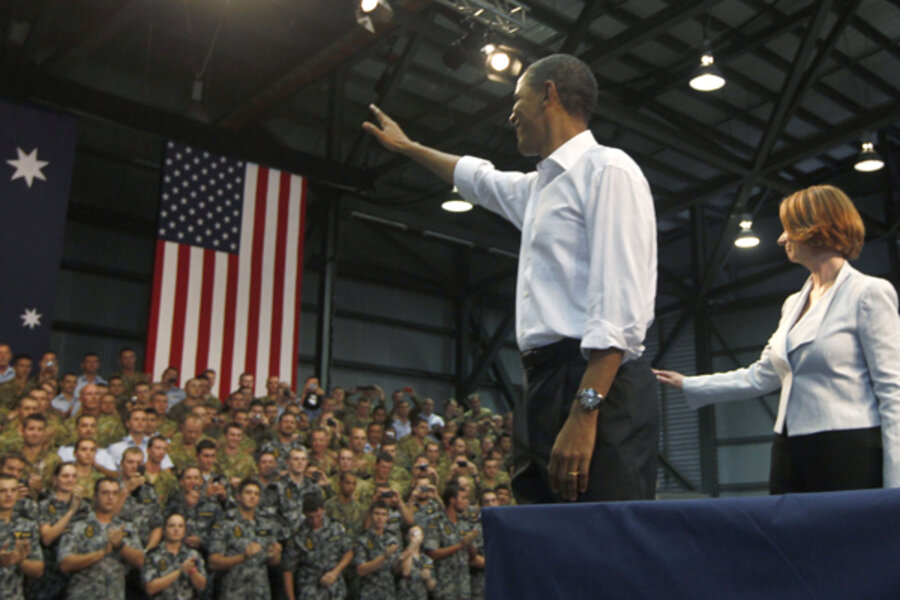

Official Chinese spokesmen have reacted calmly to President Obama’s announcement Wednesday that US Marines will be based in northern Australia, closer to the disputed South China Sea than any other US land forces.

In the midst of economic crisis “it is debatable whether now is a good time to be strengthening and expanding military alliances, and whether this accords with regional expectations,” was all Foreign Ministry spokesman Liu Weimin would say on Wednesday.

The latest in a series of US changes

But the Australian deal, which US officials said should be seen in the context of a rising China, was only the latest illustration of a clearly changing US posture in the Asia Pacific region.

Last week the Pentagon unveiled a new Air Sea Battle concept, which military officials said was needed to counter others’ “anti-access and area denial” weapons. They did not say the new concept was targeted at China, but they did not deny that China is the only potential enemy with the sort of capabilities the concept is aimed at.

Then, at the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Hawaii, Mr. Obama made progress pushing a free trade Trans Pacific Partnership from which China has been excluded.

In Manila on Tuesday, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton took up the cudgels on behalf of the Philippines in its territorial dispute with China. She pledged to help strengthen the Philippines Navy, whose vessels have recently clashed with Chinese boats; she warned China not to intimidate its smaller neighbors; and she called the South China Sea “the West Philippines Sea” in an open espousal of Manila’s position on sovereignty.

Chinese fears that Washington is seeking to contain China, and drive a wedge between Beijing and neighboring states “are not new,” says Bonnie Glaser, a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “But the US has given China lots of reasons to think it’s a real strategy.”

China has laid sovereignty claims to almost all of the South China Sea, believed to be rich not only in fisheries but in oil and other mineral resources. Those claims conflict with claims to specific islands and atolls by Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Brunei – which have periodically flared up into maritime stand-offs.

Washington says it is neutral in the territorial disputes, and that its interest in the area lies in the security of the shipping lanes that carry $5.3 trillion of world trade each year.

In fact, the US has consistently supported China’s neighbors’ demand that China resolve the disputes in a multilateral forum such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), against Beijing’s insistence on bilateral negotiations.

The issue will come up again at the East Asian Summit in Bali, Indonesia, on Friday. Obama will be the first US president to attend such a meeting, at the end of a nine day Asia-Pacific visit that has underlined, as he said to the Australian parliament Thursday, that “after a decade in which we fought two wars that cost us dearly, in blood and treasure, the United States is turning our attention to the vast potential of the Asia Pacific region.”

Beijing is clearly unhappy with Washington’s involvement in South China Sea spats. “Having forces from outside become involved would not help solve the issue and would make it more complicated,” warned Chinese Assistant Foreign Minister Liu Zhemin this week.

China insists that its policy has remained unchanged – that the details of the disputes should be set aside, and all claimants should jointly exploit any economic resources. Neighbors such as Vietnam and the Philippines complain that Chinese naval vessels have been probing their waters in an increasingly aggressive manner.

Briefing: Indian Ocean as new strategic playing field

A ploy?

Analysts here see such complaints as a ploy. “They have to make the issue hot now and involve the US because in 10 years’ time they will have nothing to bargain with China,” suggests Jin Canrong, deputy head of the School of International Studies at Renmin University in Beijing. “China will be too strong. Time is on China’s side, not theirs.”

Washington is taking advantage of the disputes “to try to expand militarily in the western Pacific,” argues Professor Zhu, stepping up naval cooperation with Manila and Hanoi, selling arms to Indonesia, and basing marines in Australia.

“China’s nationalist sentiments are bad,” he adds, “but fueling such sentiments is worse and unfortunately that’s what America is doing.”

From Washington, the view is different. “The main thrust of US policy is really not anti-China,” says Ms. Glaser. “It is reassuring friends and allies in the region, to counter the narrative that the US is in decline.”

That does not convince the Chinese media, which has made much of South China Sea issues. Even the ruling Communist Party official mouthpiece, the Peoples’ Daily, claimed in its overseas edition last week that “everything shows that the United States will provoke the contradictions which exist between countries in this region for its own benefit.”

The subdued official response to recent US moves, however, suggests that the Chinese government may be taking a different view.

“The media here are nervous, but the Foreign Ministry people seem to feel more relaxed,” points out Professor Jin. “They tend to think that the Obama administration’s policy is not containment, but something between engagement and hedging [US bets]," he explains.

At any rate, there is little fear in Beijing of a “cold war” with the US, a phrase bandied around in Washington last week in discussion of the embryonic Air Sea Battle plan.

Though recent US diplomatic and military moves in the region are not friendly, “China will not take any counter-action, there will be no tit for tat,” predicts Zhu. “I don’t think Beijing would stupidly get into an escalation or into a military race: It’s totally unaffordable.

“But this will have a poisonous effect on economic cooperation between China and the US,” he worries. “At the moment, the two powers have their backs to each other on a lot of issues,” Zhu adds. The last week or so, he believes, “will sap China’s will to cooperate.”