Can China, US strike a new deal on blind dissident?

| Beijing

As blind legal activist Chen Guangcheng spent a second day in the hospital here Thursday pondering his future, doubts arose whether he would be able to back out of a deal that he and US diplomats struck with the Chinese government for him to stay in China.

Mr. Chen continued to tell foreign reporters that he had changed his mind about the agreement, fearing for his safety, and that he now wants to go to the United States with his wife and children.

A US official was quoted as saying that Washington stood ready to help Chen whatever he decided to do, but stopped short of pledging an offer of political asylum for the human rights advocate and his family.

A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman refused to say how Beijing would respond to any US overture to renegotiate the deal, reached after several days of intense talks, allowing Chen to live peacefully and study in China, as he had originally said he wanted to do.

But Chinese experts were dubious; “I can’t say that it is totally impossible” that the Chinese authorities would allow Chen and his family to leave the country soon, says Shi Yinhong, head of the American Studies Center at Renmin University in Beijing and an occasional adviser to the Chinese government. “But I don’t think it is very likely.”

Because Chinese negotiators worked with their American counterparts, not with Chen himself while he was in the US embassy, where he had sought refuge after escaping house arrest a few days earlier, “they won’t pay much attention to what he says,” believes Professor Shi. “In international relations, changing this kind of agreement is ridiculous.”

Who's at the hospital?

US officials spent the day at the Beijing hospital where Chen is undergoing medical tests, but had been unable to see him, according to a senior official.

Chen told the BBC by telephone he believed Chinese security men were denying embassy representatives access to him. State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland told reporters that US officials had spoken to Chen twice by phone on Thursday and with his wife, and that “they as a family have had a change of heart about whether they want to stay in China.”

“We are continuing to try to ascertain and work with him on what he wants to do,” the senior official said, while Assistant Secretary of State Kurt Campbell, who helped negotiate the original deal, talked with Chinese officials Thursday.

Chen, who has sounded upset and confused in his conversations with journalists and supporters, appears to have decided on Wednesday evening that he would rather flee China than remain here, after speaking to his wife, friends, and fellow activists about his future.

Change of plan?

He told reporters he had left the US embassy, where he had sought refuge last week, only because Chinese officials had threatened that unless he did so, they would send his wife back to their hometown, where he and she had been repeatedly beaten during 19 months of illegal house arrest by the men assigned to guard them.

Salvaging the original plan, with which Chen had appeared happy as he left the embassy according to US diplomats pointing to photos of the activist smiling and hugging his American hosts, would be difficult, says Phelim Kine, a researcher with Human Rights Watch.

“It is doable, but the clock is ticking,” he argues. “The Americans need to roll out comprehensible and comprehensive measures to assure Chen that he will be OK.”

US officials had said that as part of the deal they would carefully monitor Chen and his family to ensure their safety. But within hours of leaving the US embassy Chen was telling reporters and friends that there were no US officials in the hospital where he was confined and that he had been unable to get through to the embassy by phone.

“The Americans need to make up for lost time very quickly with confidence building measures so that Chen knows that what happened in the last 24 hours won’t happen again,” says Mr. Kine.

“I would be profoundly disappointed if this craters,” said Jerry Cohen, a veteran Chinese law specialist and friend of Chen’s who advised him during his stay in the US embassy.

The plan for him to stay was “innovative and creative” said Professor Cohen, speaking on a conference call organized by the National Committee on US-Chinese Relations. Were Chen to go into exile in America “the danger would be very high that he would be neutered, be just a voice in the wilderness with no influence in his own country,” he added.

The problem, he said, was that “no details had been worked out; the challenge is how to put flesh on the bones. If it doesn’t work, he will have to leave China.”

That outcome might be in China’s interests on a number of counts, not least, suggests Professor Shi, because Chen’s presence here and US efforts to ensure he is not harassed would mean “potential long term trouble and an almost unending affair.”

Should Chen formally ask to leave his homeland with his family, “if China really wants soft power they should let him go and we should welcome him,” said Cohen.

A test-case

A decision on Chen’s future undoubtedly lies with the nine most senior leaders of the ruling Communist Party on its Standing Committee, where hardliners such as Zhou Yongkang, head of the security apparatus, are believed to have a personal animus against Chen.

The activist’s legal efforts on behalf of women subjected to forced abortions, and his subsequent persecution for seven years by local officials in his hometown, have drawn international attention and made him a figurehead of the Chinese human rights movement.

Some observers had seen the initial deal, offering Chen the chance to study in China, as a chance for reformers in the Communist Party to put their rhetoric about the importance of the rule of law into practice. “They could use this case as an opportunity,” suggests Lu Yiyi, a political researcher who works in Beijing on a project promoting open government.

Chen’s case offers a promising test-case, some analysts believe, because he has defended ordinary peoples’ rights within the system rather than challenging one party rule, as more overtly political dissidents such as Liu Xiaobo, currently serving an 11 year jail sentence, have done.

“Chen Guangcheng does not threaten the government itself, or the system,” says Li Fangping, a human rights lawyer who has represented Chen.

No change here for human rights

But the Chinese government’s readiness to allow Chen to stay “is not announcing a change in the government’s attitude to human rights activists in general,” warns Nicolas Bequelin, another Human Rights Watch analyst.

A number of Chen’s associates and supporters have been detained or put under house arrest in recent days, according to activists, and the government has shown no signs of acknowledging that local officials in Chen’s hometown might have acted illegally by holding him and his family in their house against their will for the last year and a half.

“As far as I know, after Chen Guangcheng was released from prison [in 2010] he was a free person,” said Foreign Ministry spokesman Liu Weimin on Thursday.

“The idea that the central government did not know what was going on is preposterous,” says Joshua Rosenzweig, a human rights expert in Hong Kong. “They are only dealing with it now because they have been forced to.”

World against China?

The confusion of the past 24 hours, the international media frenzy surrounding Chen’s fate, and the way in which the United States pledged to protect Chen in his own country from his own government, may have strengthened the hand of those Chinese leaders disposed to treat the activist harshly, say some analysts.

“It may reinforce the idea of a hostile world against which China has to circle the wagons,” said David Lampton, director of the China Studies Program at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University, talking with Cohen on the conference call.

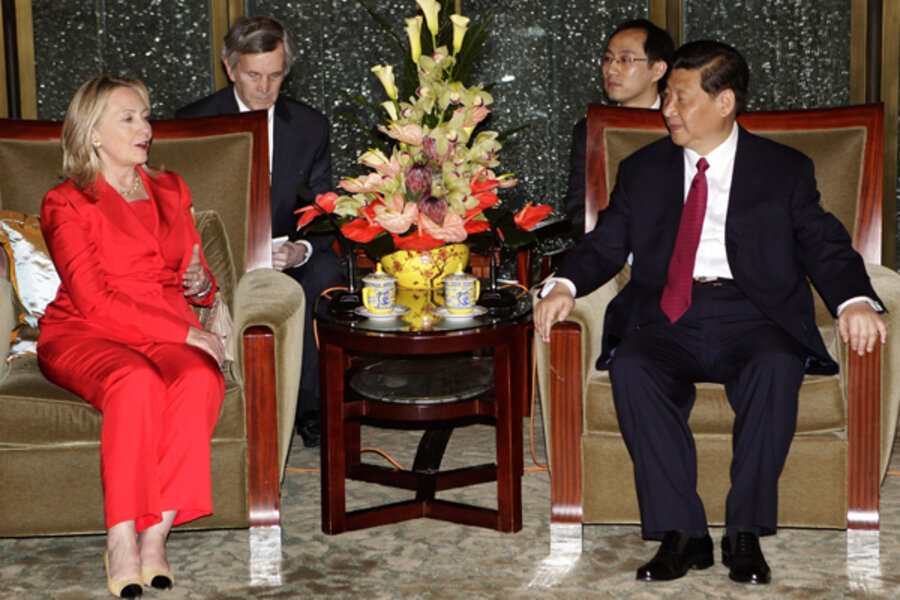

That would likely make it very hard for Chen to be granted the wish he expressed Thursday in an interview with Newsweek, that he and his family be allowed to fly to the US with Hillary Clinton when the Secretary of State leaves China at the end of this week after the current round of the US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue.

“If the Americans formally raise a demand to remake the agreement, the Chinese side will wait,” predicts Shi. “The initiative is in China’s hands and I don’t think the Chinese government will be as cooperative as it was two days ago. The process could be a long one.”

“Chen Guangcheng is America’s hot potato now,” adds Yan Xuetong, a noted international affairs specialist at Tsinghua University in Beijing. “He is not China’s problem.”