China and Japan face off: Tiny islands, big dispute

Loading...

| Beijing

The Great Hall of the People, the heart of Beijing's ceremonial political life, should have been ringing last month with toasts and speeches to fete the 40th anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and Japan.

But the banquet rooms sat silent, the celebrations canceled.

The two neighbors' ancient enmity had ensnared them again, this time in a territorial dispute over a handful of remote islands.

Hotheads on both sides of the East China Sea were calling for war. Even the coolest heads could not rule that prospect out.

"Relations are worse than they have ever been in 40 years," says Liu Jiangyong, a professor of Japanese politics at Tsinghua University in Beijing. "I don't see much chance of a war; but I think Japan is preparing for one, and we should, too."

The possibility of armed conflict between the world's second- and third-largest economies is enough to scare governments around the globe. It is especially alarming to the United States, whose alliance with Japan would draw it into any fighting.

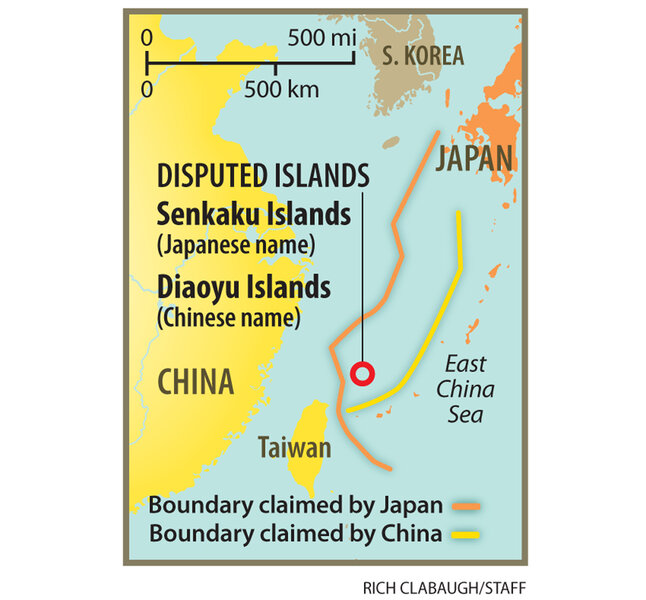

Beijing and Tokyo both claim sovereignty over five islands in the East China Sea, known as the Diaoyu in China and as the Senkaku in Japan, which administers them.

Four decades ago China agreed not to press its territorial claim on the tacit understanding that Japan would not settle or build on the rocky islets. Every now and again nationalist activists from Hong Kong or Japan would land on one of the islands and plant a Chinese or Japanese flag; there was an angry showdown two years ago when Japan arrested a Chinese fishing boat captain. But the status quo prevailed.

Everything changed on Sept. 11 this year, when the Japanese government purchased three of the islands from their private owner. Chinese leaders and media reacted with fury, spurring demonstrations in scores of cities, some of which turned violent, with people looting and torching Japanese-owned businesses.

In vain did Japanese officials try to explain that Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda had "nationalized" the islands to keep them out of the hands of the governor of Tokyo, a nationalist firebrand who was trying to buy them, likely to use them to provoke China.

Beijing declared its "base lines" around the islands, defining the exact area of its territorial claim, as the legal basis on which it claimed jurisdiction, and began sending surveillance vessels and, in one instance, two naval frigates, within 12 miles of the islands, into what Japan claims as its territorial waters.

"These patrols change the fact of only Japan controlling the islands," says Professor Liu. "Japanese administration and management will no longer be a reality."

At the same time, the Chinese Navy and Air Force staged joint drills in the East China Sea, not far from the disputed area, and the vice chairman of China's Central Military Commission, Gen. Xu Caihou, publicly urged the Army to "be prepared for any possible military combat," the state news agency Xinhua reported.

In fact, Japan's better-trained and more-professional Navy would likely defeat China's fleet should it somehow come to a shooting war, according to most foreign security analysts.

Just for show?

But the saber rattling is likely just for show, says Zhu Feng, a professor at Peking University's School of International Studies in Beijing. "Neither side wants to recklessly provoke, and both know where the limits are," he says.

Professor Zhu worries, though, that "a mismanaged crisis is very possible, and that could lead to conflict."

The waters near the islands are currently the scene of a dangerous maritime ballet involving Japanese Coast Guard vessels, Chinese fisheries surveillance ships, and Coast Guard boats from Taiwan, which also claims the territory.

So far, hostilities have been limited to water-cannon duels, as happened Sept. 24 between Japanese and Taiwanese Coast Guard vessels. But "when you have that many boats sailing around, the potential for mishap is quite high," points out Bonnie Glaser, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

The danger, adds Valérie Niquet, a China analyst at the Foundation for Strategic Research, a think tank in Paris, is that a collision, a sinking, or a fatality "could start something that would be difficult to stop," especially since China and Japan have no procedures in place to handle maritime crises.

Chinese vessels pulled out of the 12-mile zone after a few hours of patrolling last week, and Japanese Coast Guard ships have so far refrained from using force against Taiwanese fishing boats, signaling that all parties are being careful.

'There is no territorial dispute'

But neither Tokyo nor Beijing is stepping down from their position that the islands are theirs.

"There will be no policy change on nationalizing [the islands], and it is impossible to give in on this," Mr. Noda said on television recently.

He repeated Japan's insistence, especially infuriating to China, that "there is no territorial dispute" over the islands.

In China, the ruling Communist Party's official organ, the People's Daily, responded that Beijing would not compromise even with "half steps" on its demand that Japan rescind the island purchase.

The timing of this crisis does not help resolve it; China is on the brink of a once-in-a-decade leadership change when "leaders do not want China to be seen as chicken," says Zhu, and in Japan, Noda is expected to call elections in the next few months.

Facing a conservative opposition that has made the sovereignty issue a key campaign issue, "what does compromise get Noda?" asks Ms. Glaser, rhetorically.

Nationalist-minded

In the longer term, public opinion in Japan and in China is growing both more nationalist-minded and more influential, says Thomas Berger, a visiting professor of politics at Keio University in Tokyo.

"Chinese leaders have become much more sensitive to the noisier segments of Chinese public opinion," says Professor Berger, "and the Japanese public inserts itself more assertively and more erratically into the foreign-policy agenda than it used to."

Notably, Berger says, "there is a growing feeling in Japan that if they do not stand up to the Chinese there will be no end to how far they will be pushed around."

At the same time, points out Taylor Fravel, a professor of international relations at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, both Japan and China are involved in other territorial tussles with other countries, and neither wants to look weak in the current crisis.

"Prevailing in this could send a signal to rivals in other disputes," Professor Fravel suggests.

Though neither side seems to want a military conflict, China is warning that it would make Japan pay economically in a protracted crisis over the islands.

China "has always been extremely cautious about playing the economic card," stated an editorial in the overseas edition of the People's Daily late last month. "But if Japan continues its provocations, China will take up the battle."

So far, Japanese businessmen are reporting nothing more serious than delays at customs and difficulties securing Chinese visas. But the potential for damage is huge; China is Japan's largest export market (Japan is China's third-largest market), and the two countries' bilateral trade was worth nearly $350 billion last year.

Economic motivator?

On the other hand, China is not immune to the economic fallout of a drawn-out dispute.

Japan is the largest foreign investor in China after Hong Kong, pumping more than $5 billion into the country in the first eight months of this year. If anti-Japanese feelings continue to rise, Japanese investors are likely to think twice about putting money into China.

"That must be a factor" in China's thinking, says Fravel. "In the current economic slowdown, the jobs that Japanese investment creates are even more important than before."

"The economic risks should be a clear reminder to leaders on both sides to behave responsibly" in this crisis, argues Zhu. "The potential economic damage should be an alarm bell."

Behind the details of the territorial dispute, though, lies a larger picture: a shifting balance of power in Asia that some analysts say is contributing to the tensions.

China's rise – it overtook Japan in 2010 to become the world's second-largest economy – has made Beijing "more assertive, and readier to take advantage of opportunities to advance its interests," says Ms. Niquet.

That, adds Glaser, is what is happening now. "As the balance of power changes" between the two Asian giants, "China sees this crisis as an opportunity to push" Japan into acknowledging that there is a dispute over ownership of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands as a first step toward negotiations.

The Global Times, a nationalist tabloid owned by the Chinese Communist Party, put it bluntly in a recent editorial.

"Japan has been China's closest rival for a century," it argued. "China has recently achieved some strategic advantages over Japan, and it can solve the Diaoyu island issue thoroughly only by extending those advantages."

With both sides holding fast to their territorial claims, "I do not see a solution," says Zhu. "But the pressing issue right now is not a solution but how to prevent an accidental collision at sea igniting a military conflict."

Tuesday Japan's coast guard reported that four Chinese ships entered the disputed waters and had not responded to Japan's instructions to leave.

The danger, warns Berger, is that "if we do not have a resolution and a new equilibrium between China and Japan, we may have a series of such crises of this nature. There will be games of chicken over and over, and sooner or later there will be a disaster."