China agrees to sanction North Korea, but how far will it go?

| Beijing

Increasingly impatient and irritated by North Korea’s defiance of its will, China will vote alongside the United States at the United Nations Thursday to punish Pyongyang for its nuclear test last month.

After three weeks of negotiations, China and the US have agreed to broaden and tighten existing financial, economic, and trade sanctions on North Korea in response to its nuclear explosion. Russia also supports the new rules, which the UN Security Council is expected to approve unanimously in a Thursday vote.

But Beijing is showing no sign of readiness for sanctions that might threaten the secretive North Korean regime’s survival.

“Beijing sees North Korea as a problem that must be managed, not as one that must be removed,” says David Kang, an expert on Korea at the University of Southern California.

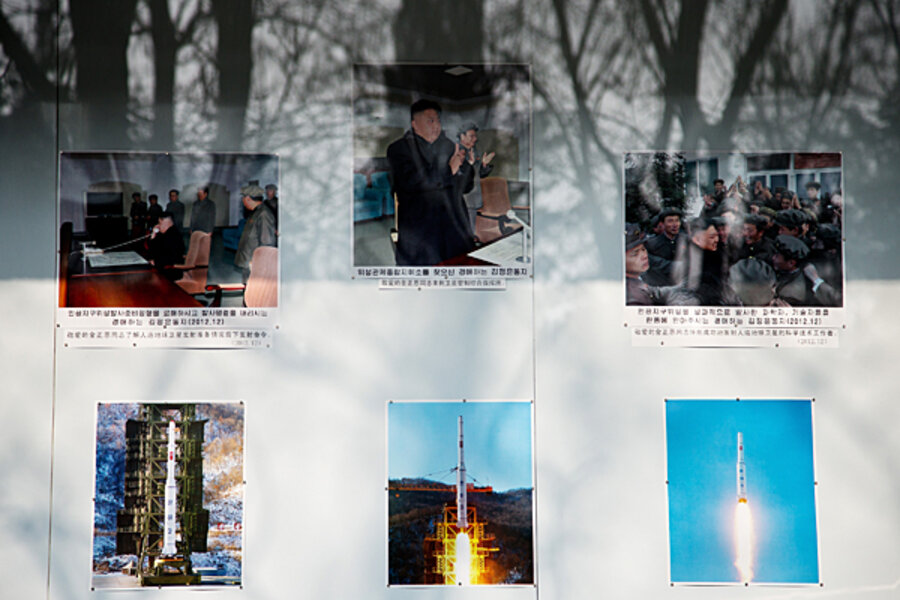

Previous UN sanctions, imposed in 2006 and 2009, failed to dissuade Kim Jong-il and his son Kim Jong-un, North Korea’s current ruler, from continuing to test nuclear devices and missiles that might carry them as far as the United States.

“There is zero chance that this new resolution will have any effect on North Korean behavior,” predicts Professor Kang. “Pressure does not work on North Korea.”

China nonetheless fought hard to tone down US proposals for much tougher punishment, say people close to the negotiations. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said Wednesday that Beijing favored a “necessary and proportionate response.”

But the Chinese government has not disguised its anger that Pyongyang launched a missile last December and carried out a nuclear test last month in direct challenges to Beijing’s public admonitions to desist.

Since a missile test last April, “the mood in Beijing toward Pyongyang has gradually worsened,” says Cheng Xiaohe, a Korea watcher at Renmin University in Beijing. “The nuclear test pushed that negative mood to a new peak.”

Since coming to power a little over a year ago, Kim Jong-un “has brushed aside Chinese friendship and made China feel extremely uncomfortable,” Professor Cheng explains.

What will sanctions look like?

That has made Beijing ready to do more to express its displeasure. The resolution due to be approved Thursday will make it harder for North Korean diplomats to transport large quantities of cash, which they are forced to do by existing financial sanctions that make banks unwilling to deal with Pyongyang.

The resolution will also step up the inspection of North Korean imports and exports, so as to crack down on Pyongyang’s purchase of technology that could help its weapons program and on North Korean military sales abroad.

The sanctions will prohibit the sale of luxury items such as yachts and racing cars to North Korea, in a bid to deny the country’s rulers some of their toys.

It remains to be seen how strictly China will impose the new sanctions. A UN panel monitoring compliance with previous sanctions found in a report last year that Pyongyang had channeled illegal exports through the Chinese port of Dalian.

“China has not put in place a system that would give a high degree of confidence that things are being stopped,” worries Scott Snyder, head of the Asia Foundation’s Center for US-Korea Policy in Washington.

Nor is Beijing prepared to countenance more openly hostile measures such as the interdiction of suspicious North Korean vessels on the high seas. Beijing has refused to join the US-led “Proliferation Security Initiative,” a 98-nation effort to prevent the spread of nuclear technology by monitoring ships and planes bound to or from North Korea.

“China will continue to maintain at least a working relationship with the DPRK,” says Cheng, using the initials by which people here refer to the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea, as the North of the divided peninsula is officially known.

That means Beijing also resisted Washington’s arguments that China should impose stricter limits on its trade with North Korea, which depends on its giant neighbor for nearly 80 percent of its imports and exports.

China and the North ‘need each other’

“More economic sanctions would mean China would have to make more sacrifices,” Cheng points out. “Economic interests play a role in holding China back from endorsing much tougher sanctions.”

At the same time, he argues, “China and the DPRK need each other.” While Pyongyang depends on Chinese aid and trade to stay afloat, Beijing is anxious to keep at least one regional nation friendly in the face of Washington’s “pivot” to Asia, which is widely seen here as a bid to contain China.

“Beijing is not an ally of Pyongyang, but at no point should China turn North Korea into its enemy,” argued a recent editorial in the Global Times, a publication of the ruling Communist Party.

China’s expected vote for sanctions on Thursday is evidence that Beijing “is ready … to resort to coercive measures,” says Cheng, but the government here is fighting shy of taking measures beyond the UN resolution.

“A number of options are on the table,” Cheng suggests, such as reducing or cutting China’s fuel and food aid, and slowing or halting investment and trade projects. “But I don’t see China taking unilateral actions in the near future.”

China’s new leaders – taking the reins at the current meeting of the country’s parliament – “may make some tactical adjustments” to Beijing’s approach to its nettlesome neighbor, says Mr. Snyder, of the Asia Foundation. “But I would be surprised if this vote represents a change in the direction of their policy.”