The Japanese apartment tower that is combating loneliness

Loading...

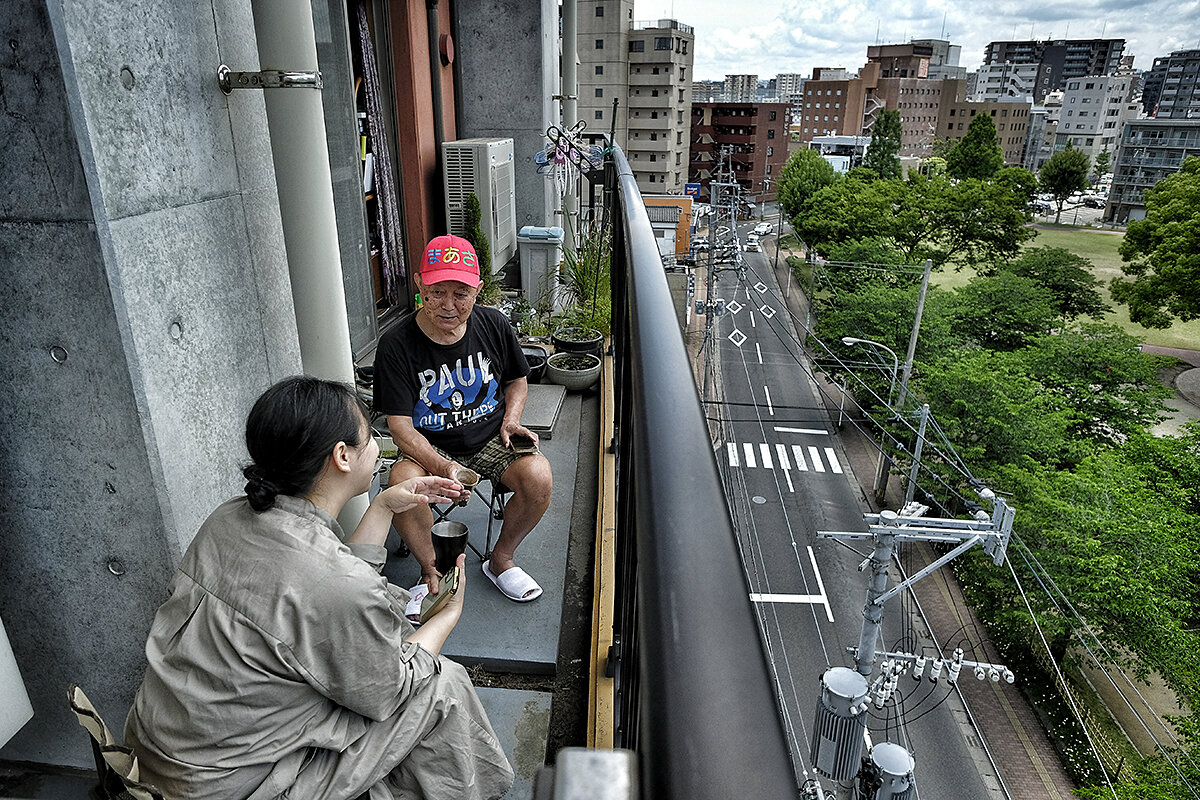

| KAGOSHIMA, JAPAN

A message on a small whiteboard near the elevator is a reminder that dinner in this apartment building is tonight at 7 p.m., as it is once every month. Many of the residents are likely to attend, since being together is the point.

Nagaya Tower, in the peaceful city of Kagoshima on the Japanese island of Kyushu, houses 43 people, ages 8 to 92, including a family with five children. With shared community spaces, the tower was built so that different generations could meet and interact. The staff is dedicated to supporting residents and connecting them with each other to generate that community life so important to combating the loneliness of older people, which has become a significant problem in Japan’s increasingly aging society.

“This community is inspired by the ancient nagayas of the Japanese Edo period,” says Nomura Yasunori, who moved here five years ago with his wife. “From children to the elderly, families, singles, from different occupations, all lived together in the same long compartmentalized house.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn an aging and often isolated society, these multigenerational apartment dwellers in southwestern Japan make togetherness a priority.

According to United Nations data, in 2021 Japan had the world’s oldest population, with 30% of its people ages 65 and over, a percentage that is expected to increase. That year, the Japanese Cabinet Office appointed a minister for loneliness and social isolation to address this situation.

According to a survey conducted in 2017 by Japan’s National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 15% of older men who live alone talk with one person or no one every two weeks, while 30% feel they have no reliable people they can turn to for help in their day-to-day lives.

Dozono Haruhiko, founder of one of Japan’s first palliative care clinics, saw how his patients could suffer from social isolation. He believed that what these patients needed was human interaction, and so, in 2011, he applied for a government grant with his idea for Nagaya Tower, which was completed in 2013.

By 6 p.m. on this evening, residents are starting to arrive with food for the communal dinner. Some of them rearrange tables to form a single one that takes up almost the entire room; others go to the kitchen to lend a hand.

“After coming to Nagaya Tower I feel rejuvenated,” smiles Kukita, who arrived three years ago with his wife. (He and several others in this story declined to provide a last name.) “Nursing homes are full of old people, but here you stay young because you are surrounded by children and young people.” Kukita says he walks every day in the park, swims in the pool, participates in the art workshop once a month, and, above all, takes every opportunity to talk and spend time with the children.

“I can learn a lot from the elderly people through the exchange,” says Takai, who is in his 30s and is one of the younger residents. “We help each other from time to time if we have a problem.”

The building was designed in a V shape so that everyone could see each other when they enter or leave their homes, allowing them to greet each other, which is not common practice in other places, according to Moemu Nagano, age 27, who has lived here for two years. “Older people place a magnet on the doors of their houses to let people know when they are going out so that others don’t worry if they don’t answer,” says Ms. Moemu.

After dinner, Kawasaki Masatoshi sings Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” to a standing ovation, making it clear that Nagaya Tower’s motto, “Life is happy when you have someone to smile with,” is more than just a phrase on a piece of paper. He loves community life and boasts of being resident zero, when he moved in 10 years ago.

“I signed up before the construction of the building was finished, and I will stay here for the rest of my life,” Mr. Kawasaki says.