Sri Lanka president’s election win disappoints Tamil expats

Loading...

| New Delhi

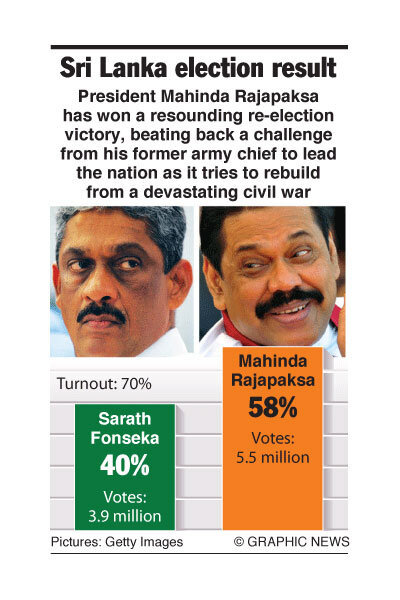

The decisive win of Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa in Tuesday’s election comes as disappointing news to the influential community of Tamils living overseas, many of whom are still reeling from his government’s defeat of the Tamil Tiger rebels last year.

Mr. Rajapaksa’s main challenger, Sarath Fonseka, was no hero to Tamils either. As Army chief, he led the ruthless campaign that routed the rebels from their stronghold in the island’s north and finished the 26-year war.

But Mr. Fonseka, beside offering the only alternative to Rajapaksa, promised he would tackle the grievances of Tamils. The Tamil National Alliance, once seen as the Tigers’ political proxy, threw its weight behind Fonseka, and most members of the diaspora are believed to have grudgingly backed this decision.

"Fonseka may have been the lesser of two evils, but he was still an evil," says Suren Surinendran, a leader of the Global Tamil Forum, a newly established umbrella organization of Tamil groups around the world. "But what choice did the TNA have?

For these voteless expatriates, Mr. Rajapaksa’s reelection underscores a question first raised when the Tigers were vanquished: What role can the Tamil diaspora now play in their homeland’s future?

Push for homeland

Most members of the Tamil diaspora, of whom there are at least 1 million, had supported the Tigers, formally called the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) – even though many Tamils in Sri Lanka reviled the rebels for terrorizing the very people they claimed to represent. Indeed, the diaspora provided most of the rebels’ funding, coughing up an estimated $300 million a year.

Some Tamil émigrés remain dedicated to the longed for “Tamil Eelam,” a separate, crescent-shaped state, which would be carved out of the north and east of the island, for which the LTTE battled.

A group called Eelam in Exile, which features a mugshot of the slain Tigers chief Villupillai Prabhakaran on its website, says elections for a “transnational government” for the Tamil state will take place in April. In countries with big Tamil populations – Canada, Australia, the US, and Britain – Tamils are being invited to vote in referendums on the Vaddukkoaddai Resolution, a 1976 document declaring the Tamils' right to form a separate state. Results from such polls suggest that the longing for Tamil Eelam still burns bright in many Tamils’s hearts.

“The roots are still there and they will grow; we all want freedom,” says the owner of a grocery store in Harrow, a London neighborhood with a big Tamil population.

Some Tamil nationalists are urging a Western boycott of Sri Lankan exports, the biggest of which is lingerie. In one film made in the US, a man halts his seduction of a young woman when he discovers her undergarments were “made in Sri Lanka.”

Time to take a backseat?

But there is also a smaller, less well-known group of Tamils overseas who say such moves are unhelpful, and out of step with the Tamils back home.

“The diaspora has to take on a subordinate role now,” says Nirmala Rajasingam, a former LTTE cadre who fled to London in the 1980s and subsequently campaigned against the LTTE, and for Tamil rights in Sri Lanka.

While the LTTE was on the rampage, she says, moderate Tamil politicians were silenced. Now there is a chance for them to once again find a voice, a process the diaspora should not jeopardize by funding rival parties.

For activists like Rajasingham, Tamil émigrés now have a vital role to play, pressing for investigations into alleged human rights abuses during the war, and for the political solution that most observers believe is necessary for peace: devolution to the regions and power-sharing at the center.

For former Tiger followers dead set on Tamil Eelam, this is a controversial view. But Rajasingham says that since the LTTE was defeated, she has heard more British Tamils dare express it.

The election offered a dismal prospect whatever the outcome, she says, “and now Tamils in Sri Lanka have to create a democratic political culture – for themselves.”