Can Afghanistan economy thrive without poppy?

Loading...

| New Delhi

Why does the Afghanistan economy matter to the world?

Let's do the math. President Hamid Karzai, backed by NATO commanders, says the country needs 400,000 Afghan soldiers and police to defend itself. That would cost about $10 billion annually.

Afghanistan's current budget: $1.1 billion. And $400 million of that comes from foreign donors.

To close that gap, Afghanistan cannot rely on the current dynamo of its economy – poppy. While it accounts for nearly 30 percent of the country's gross domestic product, and 90 percent of the world's heroine, it's unlikely to ever be legalized and, therefore, taxed. On Wednesday, the government launched a massive poppy eradication program, starting in the south.

What can be done to build up the remaining 70 percent of the economy?

Magic bullets

Policymakers zero in on two areas to grow Afghanistan's $11.4 billion economy: agriculture and mining. Farming has big potential by virtue of its huge workforce, and mining holds the prospect of untapped value in the billions of dollars. Both, however, will take years to develop and improved security to encourage investment.

Mining is currently a $52 million a year industry – less than 1 percent of the economy. But a few big-name projects highlight its potential. In a deal with the Chinese in 2007, the Aynak copper mine will bring in $1 billion of annual revenue for Kabul. And bids were due Feb. 15 to exploit Hajigak, a massive iron ore deposit.

"That's estimated to bring in up to $3 billion a year in government revenues for centuries," says Craig Steffensen, Afghanistan country director for the Asian Development Bank. "I think the mining sector is this magic bullet that everyone is looking for to sustain things without [foreign donors] having to cover costs until kingdom come."

Of course, magic bullets are rare. Western investors have hesitated to enter Afghanistan because of an uncertain regulatory environment, corruption, lack of transparency, and lack of security, says James Yeager, an American geologist who advised the Afghan Ministry of Mines.

Mining: the Chilean model

Still, he points to Chile as what's possible for Afghanistan. Thirty years ago it had a fledgling mining industry, he says. "They changed their laws to make mining very favorable. They cleaned up their corruption act. Today they are the world's leading producer of copper."

Mr. Yeager hesitates to put a dollar figure on Afghanistan's mineral wealth, saying it requires more research. Then, to develop any deposits, firms must conduct exploratory drilling, arrange financing, and line up engineers. Normally those steps would take three to five years, Yeager says. "Then you couple that with the fact that there's really no infrastructure in Afghanistan, no drill companies."

The Aynak copper mine shows that some of the hurdles can be surmounted, though the deal has been criticized for lack of transparency and allegations of bribery. Indeed, natural resources often become a corrupting influence in developing nations. They also can tie economies to severe boom and bust cycles.

Afghan leaders are taking steps to avoid those mistakes. The Aynak deal was structured to give the government a fixed stream of revenue, shielding it from commodities crashes. And the government has been accepted as a candidate for the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, which would put mining revenues into accounts that are supervised internationally, says Mr. Steffensen.

Agriculture: the American angle

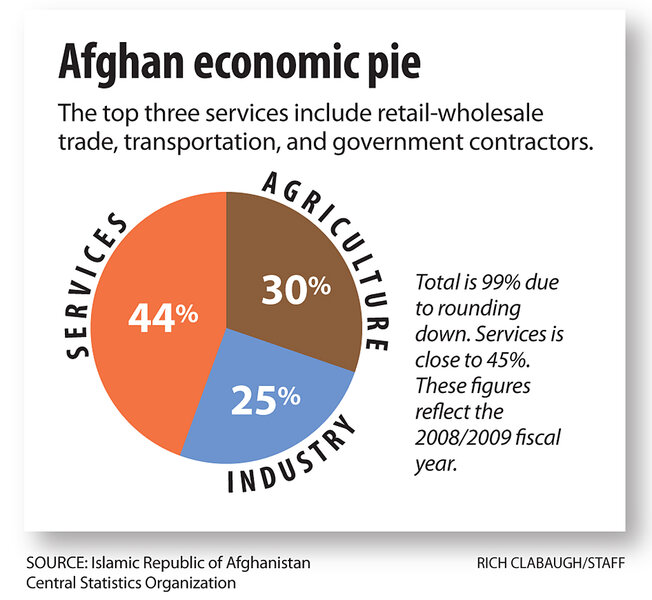

Another area for growth is agriculture. Worth $3.3 billion, it's not actually the biggest sector – it's No. 2 after services, a $4.4 billion segment dominated by trade, transport, and government support.

But improvements made in agriculture can be applied across the widest swath of the country. "The most likely areas of improvement are in the agricultural sector because more than 40 percent of people in Afghanistan are busy in this sector," says Abdullah Saleh, an analyst with the Afghanistan Investment Support Agency.

The United States is spearheading a $500 million investment this year in Afghan agriculture. This involves improving seeds, offering farmers credit, improving irrigation, and encouraging food-processing factories.

In the southern province of Helmand, USAID has set up an agribusiness industrial park with an airstrip, and, so far, has signed up a cooking oil manufacturer. But it remains treacherous for many farmers to transport their product to the capital. Fixing that problem is one goal of the Marjah offensive – launched by NATO and Afghan forces in mid-February – underscoring how development requires security.

"No one likes to go to a poor country that needs so much in terms of the social sector and put a bunch of money into the military," says Jeremiah Pam, a guest scholar on postconflict economics at the US Institute of Peace in Washington.

But "once you have security ... there are often surprises in terms of the capacity that is finally allowed to bloom."