Afghanistan war: lessons from the Soviet war

Loading...

| Lashkargar, Afghanistan

It was early summer, 1982. The Soviet war in Afghanistan was gathering momentum against the mujahideen, the country's disparate but increasingly widespread resistance movement. I'd just trekked for 10 days across rugged mountains from neighboring Pakistan to the beleaguered Panjshir Valley, an assertive thorn against the Red Army's might barely 40 miles north of Kabul.

I was traveling with a half-dozen mujahideen guerrillas accompanying a French medical team being sent to replace a group of volunteer doctors working clandestinely among the civilian population.

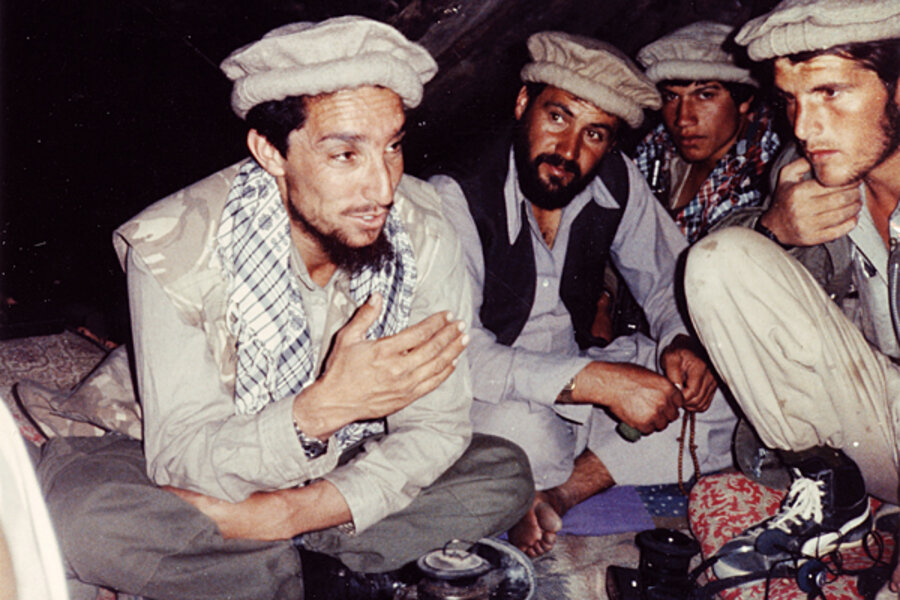

My purpose was to report on the largest Soviet-led offensive against the mujahideen to that date. More than 12,000 Soviet and Afghan troops would attempt to crush 3,000 fighters led by Ahmed Shah Massoud, known as the "Lion of Panjshir" and one of the 20th century's most effective guerrilla commanders.

Last month's NATO-led operation in Marjah in Helmand Province – the largest offensive of the current war – put me in mind of the Panjshir. There are clear lessons from the nearly decade-long Soviet occupation that the international community might heed in its ninth year of war in Afghanistan, with the biggest battle campaign now under way.

The Panjshir push was roughly the same size as the Marjah offensive – called Operation Moshtarak – and involved 10,000 to 12,000 coalition and Afghan troops. In the Soviet war, Western journalists reported primarily from the guerrilla side. But in contrast to most of today's media, embedded with NATO troops, we had constant access to ordinary Afghans. We walked through the countryside sleeping in villages, with long evenings spent drinking tea and talking with the locals. Frank conversation doesn't happen when one party wears body armor or is flanked by heavily armed soldiers: Afghans will only tell you what they think you want to hear. Or, even more crucial, what suits their own interests. Hence the highly questionable veracity of opinion polls in Afghanistan today.

Similar to the Marjah offensive, the Soviets warned the population of the impending attack with propaganda leaflets and radio broadcasts. They appealed to the Panjshiris to support the government in return for cash and other incentives, such as subsidized wheat. Their tactic was to force the guerrillas out, but allow the civilians to remain. To make their point, the communists lambasted the guerrillas as criminals supported by foreign interests in the tribal areas across the border in Pakistan, a tactic similar to those used by the Americans against the Taliban today.

APPROACHING THE PANJSHIR THAT SUMMER of 1982, we skirted the massive Bagram Air Base, today run by the Americans but then a hugely fortified Soviet bastion blistering with helicopter gunships and MiGs. On reaching the outer edges of the mighty Hindu Kush, we encountered groups of refugees hiding among the gorges. Days earlier, Massoud had evacuated the area's 50,000 or more people, somewhat less than the population affected by the Marjah campaign. He did this to minimize civilian casualties and to give his fighters free rein.

Before dawn the morning after we arrived, we could hear the ominous drone of helicopters. As the throbbing grew louder, tiny specks appeared on the horizon, gunships sweeping over the jagged snowcapped peaks like hordes of wasps. Soon the hollow thud of rockets and bombs were pounding guerrilla positions. Intermittently, pairs of MiG-23 jets and the new highly maneuverable SU-24 fighter bombers shrieked across the skies dropping their loads.

With two journalist colleagues, I climbed to a 7,000-foot vantage over the valley. Dozens of front-line guerrillas, looking like Cuban revolutionaries with their long hair and beards, lounged among the rocks in the bright sun watching the spectacle. Grinning, they handed us glasses of tea, oblivious of helicopters roaring barely 500 meters overhead. Massoud's strategy was to empty the valley, let the Soviets in, and have fighters hit the occupation forces in their own time.

It was reminiscent of a 19th-century painting of picnickers casually watching a distant battle. We counted no fewer than 200 helicopter sorties that morning, while scores of tanks and armored personnel carriers ground their way up the riverbed, the only way to penetrate the valley because guerrillas had mined the road. Unlike the current anti-NATO insurgency, however, the use of improvised explosive devices was limited; while suicide bombers, a relatively recent tactic introduced by Al Qaeda, were never used by the mujahideen.

There seemed to be many simultaneous operations: Across the valley, M-24 gunships circled like sharks to attack guerrilla positions. Farther on, trucks mounted with rockets fired into mountainsides. Just below, a Soviet machine gun leveled off bursts against guerrillas among the boulders above. Nearby, shirtless Red Army soldiers took breaks sunning on looted carpets spread on the flat roofs of houses, while others redeployed, jogging single file through shrapnel-torn mulberry trees.

The Soviet/Afghan force quickly took the valley, proclaiming victory. The reality was far different. Massoud's experienced guerrillas suffered few casualties and, within days, launched assaults against the entrenched Red Army troops. Afghan government soldiers, too, poorly paid and disheartened, slipped out at night with their weapons to join the resistance.

Massoud eventually made a truce with the Soviets. This enabled the Red Army a "take and hold" policy with several garrisons in the Panjshir. Some civilians returned, while the guerrillas established their own concealed bases in mountains beyond. The truce was much criticized by rival groups of mujahideen, but it was part of a long-term strategy: Massoud had no intention of collaborating with the regime. Occupation troops first had to leave before any unity government could be formed. It's the same refrain today by the Taliban, Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin, and other opposition groups.

For years, Massoud kept the Soviets tied down while focusing on other areas and building a highly proficient regional force denying the communists swaths of countryside. The mujahideen – like the Taliban now – always felt they had time on their side. All they needed to do was wear down the Red Army. At the height of the occupation, the Soviets commanded 120,000 troops in Afghanistan, compared with the 150,000 coalition high expected by next fall with completion of the US troop surge. When the Soviets, who suffered at least 15,000 deaths and thousands of injured, pulled out in February 1989, they had little to show but widespread destruction of much of the country. Three years later, the Moscow-backed regime in Kabul crumbled. Today, it's as if the Soviets had never been there.

Unlike NATO forces, who now make pointed efforts to protect civilians, the Soviets and their Afghan cohorts often deliberately targeted local populations. Throughout its war, however, the Red Army held little more than the main towns. The countryside remained largely in the hands of the mujahideen. Similarly, today, 70 percent of the country is ranked as "insecure" by the United Nations.

THE parallels of the panjshir with today just keep rolling. Today's insurgents fight much like the mujahideen; and, in fact, many now call themselves mujahideen. Many commanders earned their battle spurs during the Soviet war. Their fighters hide among the locals and, often, are the locals. If things get tough, they deploy elsewhere.

Like Marjah, a deliberate joint NATO-Afghan operation, the Soviets made a point of involving Afghan partners and constantly extolled the effectiveness of the Kabul regime in the hope that Afghan security forces would assume the brunt of the war. In reality, the Soviets were running the show just as US, British, and other forces are today.

Ironically, the Soviets did succeed in creating an effective Afghan fighting force. Following the Red Army withdrawal, the communists fought hard and well against fundamentalist mujahideen supported by the Pakistani military in eastern Afghanistan. The communist regime finally fell for political, not military, reasons. There's little doubt that Afghan security capabilities can be improved today, but can the Kabul regime achieve acceptance?

Red Army commanders were very aware that they couldn't trust "their" Afghans. Massoud's mujahideen enjoyed full details of planned operations before launch. Many government, military, and police officials, including senior commanders, secretly collaborated with the resistance, just as pro-Taliban and other insurgent collaborators have infiltrated most ministries of the current administration.

The Soviets also succeeded in building a highly effective network of informers and often thwarted resistance operations based on this intelligence. But they never gained the upper hand. The more effective guerrilla commanders always seemed to keep two steps ahead of the game. (Twice, while reporting for the Monitor during the 1980s, I was nearly captured by Soviet heliborne troops after being informed upon by local Afghans.)

Moscow's attempts to establish hard-core militia fronts by purchasing their allegiance also faltered. The old adage of "you can only rent an Afghan, you can never buy him" remained the rule of thumb. Many militia had "just in case" arrangements with the mujahideen, just as today numerous police and military units collaborating with NATO forces have their own deals with the insurgents.

While the coalition may claim the Marjah offensive routed the Taliban, it will probably have little impact on the long-term fighting capability of the opposition, even if NATO holds terrain captured.

To claim success shows a poor understanding of Afghanistan. Only a small proportion of the insurgents are actually fighting. The majority of sympathizers will have buried their weapons or simply blended in among the civilians. Others are in the process of deploying elsewhere, just as Massoud used the interim to organize fighting fronts throughout the north. There's no way that all these areas can be controlled militarily.

Many of the Western governments operating in Afghanistan focus on their own zones, such as the Dutch in Uzurugan and the Germans in Kunduz. Most officers come for six-month deployments, a period in which no one can even begin to understand this country. It is this lack of understanding about Afghan culture and thought that is the biggest problem today. Crucial, too, is the need for a long-term approach for the next 30 years. Talk of exit strategy only plays into the hands of insurgents biding their time.

The Western missions, barricaded in Kabul compounds, are out of touch with what's happening on the ground. So are their intelligence operations. They spend billions on recovery or security initiatives, yet are reluctant to invest in credible information efforts.

As the Marjah operation demonstrates, there is still the belief that the problem can be resolved by clearing out the insurgents militarily, and holding the territory while installing new top-down structures – "a government in a box."

For most Afghans I've talked to on recent trips to Kabul and eastern, central, and southern Afghanistan, justice, not security, is the principal concern. Even where the military is in control, Afghans slip out to Taliban-controlled areas to seek fair dealing, having more confidence in Taliban sharia courts than in Karzai-regime judges. They see lack of rule of law and international community failure to develop a functioning economy, particularly in the countryside where 80 percent of Afghans live. And they increasingly perceive the coalition as a foreign occupation force, much like the Soviets.

The Soviets thought they could subdue Afghanistan through brute force, political indoctrination, and bribes. They wanted to put across the notion that their form of government had far more to offer than the jihad embraced by the mujahideen. They lost.

The West, following dangerously close to the path of its Soviet predecessor in Afghanistan, must show that it isn't there to impose its own views but to help ordinary people feel they have a future.

•Edward Girardet, author of "The Soviet War" and a forthcoming 30-year retrospective on Afghanistan, has reported for the Monitor since 1979.