Pakistan names new Army chief. Will this one stay in the barracks?

| Islamabad, Pakistan

The last time Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif replaced the head of the Army, he chose an obscure young lieutenant general. He reasoned that the officer would be malleable and less likely to uphold the military's tradition of meddling in government. The year was 1998, and the young officer was Pervez Musharraf.

The rest, as they say, was history: A year later, as Mr. Sharif looked to oust Gen. Musharraf, the general instead ousted him in a coup and ushered in nine years of military rule with Musharraf himself at the helm.

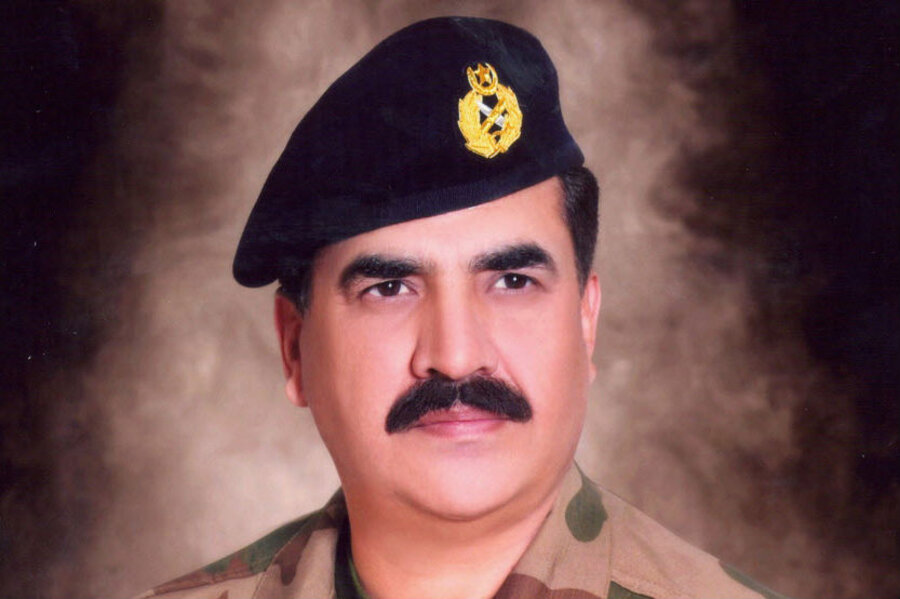

On Wednesday Sharif, once again the elected civilian leader of Pakistan, appointed another lieutenant general as head of the Pakistani Army. Raheel Sharif will replace the current Army Chief Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, whose term ends Nov. 29.

Sharif, who is no relation to the president, is a career infantryman who was previously in charge of training and evaluation, according to news reports. The president also appointed a new chairman to the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee.

This time, the change of personality at the top of the powerful Army is not likely to have the wide-ranging consequences of 15 years ago.

Under Gen. Kayani, a delicate equilibrium has developed between the Army and Pakistan’s civilian setup. The once coup-prone nation is more stable. And Kayani is credited with not interfering in Pakistan's first transfer of power from one democratically-elected government to another following Sharif's election in May.

Few expect more coups are in the offing. But an era of civilian supremacy has also not yet arrived. Instead, Pakistan's military take a back seat to civilian leaders, but retain substantial leverage thanks to its network of intelligence agents and vast business interests, all of which elude civilian control.

“The military has taken more hits to its image than ever before so it is not able to take such an active role in politics. They continue to have a lot of influence behind the scenes but they are sensitive to things that could be unpopular,” says Michael Kugelman, senior program associate for South Asia at the Woodrow Wilson International Center.

Mr. Kugelman says the US operation that killed Osama bin Laden is a source of this new self-consciousness. The raid was deeply embarrassing to the army as the Al Qaeda leader was found living less than a mile from Pakistan’s Military Academy in Abbottabad.

Private media explosion

Another factor is the explosion of private media in Pakistan. News outlets have subjected the military to scrutiny and criticism that it had not experienced before. Ironically, the growth of private media channels began in 2002 under Musharraf, who did not foresee that these channels would contribute towards the end of his military rule. Today Pakistan boasts 42 newspapers and 16 news channels in seven different languages.

With the US reducing its role in neighboring Afghanistan and with ongoing controversies inside Pakistan over the Obama administration's drone campaign targeting alleged militants inside the country, it's still possible that Pakistan's military leadership will grow more assertive, analysts argue. That doesn't mean the military will be taking over, but rather that it will set even more of its own policy, particularly when it comes to Afghanistan and Pakistan's restless northwest.

“In the last few years the civilian government and military have become more aligned, but without Kayani that may go. This is the potential for tension. The general concern is that he [the new chief of army staff] will be more hard-line because of domestic issues,” said Shamila Chaudhary, South Asia analyst for the DC-based New America Foundation, a think tank.

The Pakistan army is a key partner in attempts to stabilize Afghanistan. It receives around $700 million in aid from the US each year, more than 60 percent of total US aid to Pakistan. Many view the cash flow to the army as an attempt by the US to temper the army’s close links to the Afghan Taliban, which it has supported at various times to counter what Pakistan views as growing Indian influence over Kabul.

A hotter war in Afghanistan

A decline in Pakistani civilian-military cooperation could lead to a hotter war in Afghanistan, with the Pakistani military funneling more support to the Taliban in defiance of America's and Sharif's concerns about blow-back in Pakistan. Relations between Kabul and Islamabad were strained by the recent revelation that Kabul had offered support to the Pakistani Taliban in an attempt to counter the Pakistani army’s support for the Afghan Taliban.

Since Pakistan's founding in 1947, the military has thrice ousted what it considers weak civilian governments. The Army wields enormous influence through a web of proxies in Afghanistan, Balochistan and northern Kashmir, and its nurses an empire of business interests valued at nearly $20 billion that range from cement to cornflakes.

The Army has lent only tacit support to the civilian government’s plan to negotiate with the Pakistani Taliban. Analysts say that the Army will allow the government to continue to push for peace talks in order to ensure they have the necessary political cover for a military operation against militants when the talks fail.

The government’s planned peace talks with the Taliban took a hit after a US drone strike killed the militant group’s leader, Hakimullah Mehsud, on Nov. 1. His replacement, Mullah Fazlullah, has ruled out talks with the government and vowed to continue attacking soldiers and government officials to avenge Mr. Mehsud’s death.

“It is a dangerous situation and it is polarizing Pakistan,” said Rasul Bakhsh Rais, a professor of political science as the Lahore University of Management Science.