Greek debt crisis: Bailout likely, but will it be enough?

Loading...

| Boston

Azerbaijan, Colombia, Egypt, and... Greece. This week, the Hellenic Republic joined a rather unfortunate club of countries whose bonds are rated "junk" by Standard & Poor's, setting off a flight from Greek debt and emergency meetings across Europe to arrange a bailout.

Neighbors with high levels of debt have been swiftly punished. S&P has also cut the debt ratings for Spain and Portugal, and borrowing costs for both governments have surged this week.

The euro fell to a 12-month low against the dollar Wednesday. The risk premium to hold Spanish debt – the price investors demand over much safer German debt – rose to more than 1 percentage point. Investors are now demanding more than 11 percent return to hold Greek 10-year bonds, compared with a little more than 3 percent for the German 10-year, the European benchmark.

IN PICTURES: The top 10 things Greece can sell to pay off its debt

Politicians in Europe and bankers at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have been scrambling to secure a bailout package for Greece, particularly since there are growing fears of "contagion" – the financial woes of Greece spreading to financially weak neighbors like Portugal.

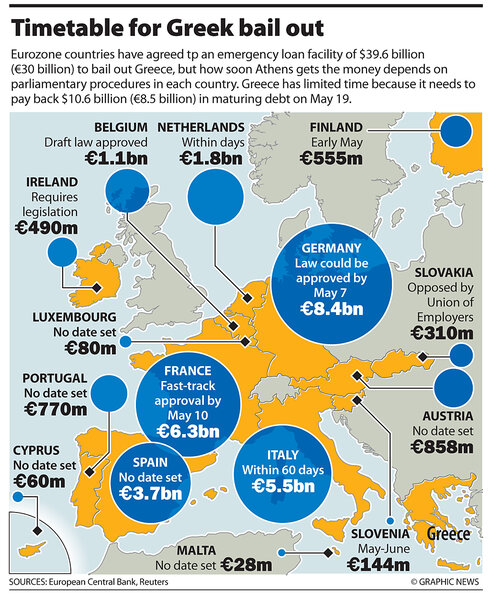

Time is short because the country has about $11 billion in debt coming due in May. The current yield on its debt effectively prices Greece out of the private market. That leaves aid from the IMF or other governments the only course of action. But how much money will Greece need? The number appears to be rising ever higher.

How much?

Earlier this week, European leaders and the IMF were mooting a €45 billion ($60 billion) bailout. On Monday, economists Piero Ghezzi and Chrstian Keller at Barclays Capital argued in a research note that €45 billion would tide Greece over for only about a year, and that Greece needs at least €90 billion, coupled with tough austerity measures at home.

On Wednesday, IMF boss Dominique Strauss-Kahn told German lawmakers in a closed meeting that the Greek bailout will need to be between €100 billion to €120 billion, according to the Wall Street Journal, which cited MP Jürgen Trittin for the information.

This wasn't supposed to happen when the euro, the common currency for much of Europe, was introduced in 1998 (Greece joined in 2000). Unlike Egypt or Colombia, which can print money in times of financial crisis, undermining the value of both their domestic currencies and ability to repay foreign debts, euro membership was supposed to come with a stable currency that would make repayment easier.

It also came with strict rules on government borrowing that would prevent any need for a bailout. The Maastricht Treaty that established the currency union even came with an ironclad promise of no inter-European bailouts, easing fears of members like Germany that they would be asked to pony up for more profligate euro members.

In reality, currency union has tied European financial boats together as never before – even as Greece, for example, has pursued radically more costly fiscal policies than, say, Germany. While in practice other eurozone nations could refuse to bail out Greece, the fate of the common currency is tied to the country, and arguments similar to the "too big to fail" discussions that led to US bank bailouts are coming to a fore.

Financial union without political union has long been the major flaw in the common currency to critics, and one that is feeding euroskepticism, particularly in Germany, where many long for the vanished and stable deutschemark.

"The would-be members of the euro club are not like railroad cars just coasting along or waiting passively in the Brussels switching yard," German author and political scientist Josef Joffe warned in a piece for the New York Review of Books in 1997, on the eve of monetary union. "Each has its own 'engineer' – its government whose politicians face reelection. Each has its own 'engine' – its macroeconomic policy that determines spending and taxing, debt and interest."

Mr. Joffe argued that political differences on domestic economic policy would almost inevitably lead to a "decoupling" of euro economies, and create strains like the ones we are seeing today.

Crucial Germany

The Germans will play a crucial role in any bailout of Greece. The wealthiest member of the eurozone, Germany will be expected to kick in the lion's share of the cash for Greece, something that is upsetting many German voters and politicians, who ask why they should have to pay the price for a southern European neighbor that has stubbornly refused to get its financial house in order.

Some German politicians have also been calling for "haircuts" on Greek debt – a reduction in the amount of money owed that would make the bailout cheaper for the governments involved and increase the chances Greece could get back on its feet. The private sector hates the idea – it amounts to a kind of limited default – and concerns about debt reductions have also weighed on European debt markets.

"As the contagion risk of a debt restructuring at this point could be significant, it is irrational for the EU and the IMF to push Greece into any restructuring early on as part of a bailout package – even if a restructuring cannot be excluded at a later point,"' argued Ghezzi and Keller at Barclays.

They point out that the real problem for Greece is not its short-term need for cash, but persistent deficits. They imagine a scenario in which a €90 billion package over three to four years could get Greece back on its feet. But they call for it to be coupled with an increase in the tax base and massive cuts in government spending that would turn a fiscal deficit that ran at 8.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2009 to a surplus of 6.4 percent by 2014.

"It cannot be emphasized enough that even such a large financial package would by no means present an 'alternative' to the necessary fiscal adjustment by Greece," they wrote. "Rather, it would give the fiscal adjustment a chance in the first place by providing affordable financing ... and thereby avoiding Greece's immediate default."

Is such a fundamental restructuring in Greece likely? That, at the moment, amounts to the €100 billion question. "The trouble is that the Greeks need a basic change in lifestyle (paying taxes, declaring income, having real jobs) and it probably will take quite a nasty crisis to convince them to do so," explained David Goldman, former head of global credit strategy at Credit Suisse and now an editor of First Things online magazine, in an e-mail.

Greece's powerful public-sector unions signaled their sentiments this week. Transport workers held a strike on Tuesday, and they have been warning for months that they don't intend to bear the brunt of the pain from a problem they blame on government corruption.

IN PICTURES: The top 10 things Greece can sell to pay off its debt

Related: