European students protest US-style 'capitalist education'

Loading...

| Frankfurt, Germany

Ten years ago, Europe's ministers met in Bologna, Italy, to create a sort of common European education market. A three-year bachelor's degree would replace the longer first degrees offered by most European universities. It would be followed by a two-year master's. Students would have to complete work within a set time frame to save taxpayer money.

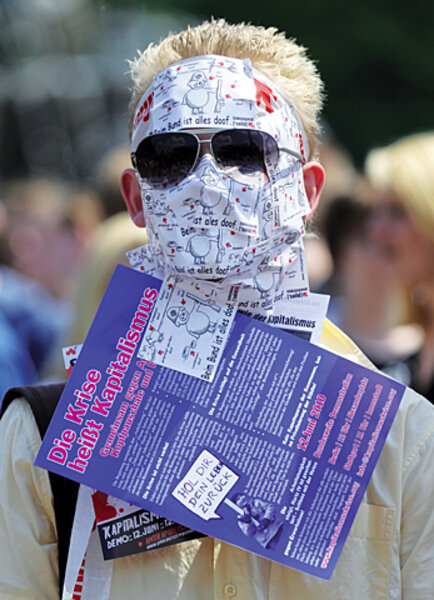

But what started as an attempt to foster internationality and mobility, known as the Bologna Process, ignited a revolution. Hundreds of thousands of students have taken to the streets in recent years to protest what they see as American-style privatization – energizing debate over how struggling Eurozone countries can keep intact a sacrosanct principle of free education for all.

"Education is just one aspect of Europe submitting to an Anglo-American paradigm that extends from finances to management to the economy," says Michael Liebig, a political scientist at Frankfurt's Goethe University. Notions of employability and marketability raised at Bologna, Liebig says, threatened cherished tenets. "But a lot of people are sobering up."

In Spain, students have occupied university buildings, blocked train lines, and interrupted Senate meetings. In Paris, they have paralyzed the metro. In Prague, protesters held graduate "auctions" where fictitious companies auctioned off the most "efficient" graduates. Philosophy majors didn't sell well.

"Education is a right, not a commodity," proclaimed one banner plastered all over the University of Osnabrück, in Germany's Lower Saxony. In March, thousands of demonstrators greeted the European education ministers at the Bologna Process's 10th anniversary celebration in Vienna and Prague.

A voluntary agreement among 45 countries – from the European Union and 19 others, including Russia and Turkey, the Bologna Process "has acted as a catalyst for change in all countries across Europe," says Ligia Deca, head of the European Student Union in Brussels. "University systems where reform was needed have been forced to make changes."

Trials of a uniform standard

Eastern European countries like Hungary and the Czech Republic saw in Bologna a chance to bring communist-era universities closer to Western European levels. The Czech Republic wants to raise its number of university graduates – now the lowest in Europe. Germany supports shorter, more work-related degrees.

But to many, Bologna is synonymous with making students pay. England was the first European country to introduce tuition fees in 1998, paving the way for other countries, such as the Netherlands, Austria, Italy, Spain, and Portugal to do the same. But fees remain minimal (except in England). In Scandinavian countries, studying remains basically free. Until recently, German universities were legally prevented from charging students, but the constitutional court overturned the law. Some regions, like Hessen, now charge modest fees. But Bologna has intensified fears of education becoming a restrictively expensive commodity.

Goethe University campus in Frankfurt's Bockenheim neighborhood has antique, overcrowded lecture halls. It has produced such graduates as Karl Marx and Albert Einstein. But with its emphasis on what Mr. Liebig calls the "economics of education," Bologna risks dismantling the core strengths of a system "that has generated a competitive edge in terms of science and technology." "For the majority of students, university education has been reduced to digesting existing knowledge," argues Liebig.

The 'McDonaldization' of universities

Condensing degrees that used to take five or more years into three years has forced universities to cut back on teaching hours. "What we used to do in eight or more semesters we have to digest in six semesters – I don't agree," says Eric Reifschneider, a Frankfurt student who organized a national demonstration this past winter. Mr. Reifschneider says students today have too little time to think.

"The minute you say 'bachelor,' you set the McDonaldization of German universities in motion," Ulrich Beck, a professor of sociology at Munich's Ludwig Maximilans University, wrote in the newspaper Frankfurter Rundschau recently in a article titled "Fast Food entails Fast Education."

But others agree that Bologna has forced Germany to shake up a bureaucratic, underfunded system. Across Europe, there is little incentive for students to leave publicly funded universities. At the same time, high dropout rates – 40 percent in France, for example – plague Europe in general, particularly Germany.

Most German students do not graduate until age 26, studies show.

The Humboldt ideal – which promotes giving students time and freedom to shape their studies – works only for the disciplined few, says Wolfgang Fach, co-rector of Leipzig University. Six of 10 philosophy students drop out, he says. By giving students financial incentive and a deadline, Bologna might get them to take studies more seriously, he says.

While the goal of the Bologna Process, to harmonize systems across Europe, is good, its implementation is problematic. But Ms. Deca of the European Student Union says this is normal. "You need to have an education system that makes students employable," she says, "but that doesn't mean you have to make higher education look like a corporation."